There’s no picture of Jimmy Savile attached to this blog. Press and TV coverage has repeated images of him, seemingly to demonstrate what an unsavoury person he was (shell suit, cigar, endless gurning). Such images encourage the speculation “why didn’t anyone object?” or “why didn’t anyone find him out?” The answer lies, unfortunately, with television more than any other institution.

The joint NSPCC/Metropolitan Police report Giving Victims a Voice, published on 11 January, gives one answer. There have been 450 allegations against Savile since the scandal first broke, engulfing the BBC. More of these accounts relate to the National Health Service premises to which he had access than to the BBC. But the latest allegation relating to the BBC is shockingly recent: the recording of the last Top of the Pops in 2006. And although the word ‘allegation’ is used throughout the report, the authors are clear that “On the whole victims are not known to each-other and taken together their accounts paint a compelling picture of widespread sexual abuse by a predatory sex offender. We are therefore referring to them as ‘victims’ rather than ‘complainants’ and are not presenting the evidence they have provided as unproven allegations.” (p.4)

It is equally clear that these victims feel that, at last, they can come forward and be believed. Ros Coward vividly describes the victimisation of the victims that often follows an accusation of abuse: “when his crimes emerged I witnessed a community that chose on the whole to push it under the carpet as a bit of an aberration by an otherwise successful man. Indeed, several people expressed sympathy for the abuser and some dismissed it in terms of “everyone gets groped in their childhood”. None of these people would condone abuse or were in any way responsible, but neither did they want their worldview or existing relationships ruffled by what was obviously considered embarrassing and which threatened to disrupt the status quo. There was a bizarre sense that it was the children who had blown the whistle who had caused the disruption, not the abuser.” This seems to have happened to the few brave individuals who reported Savile whilst he was still alive. Others had been intimated by Savile’s direct threats.

Television celebrity was at the root of Savile’s power. As the NSPCC report says, “It is now clear that Savile was hiding in plain sight and using his celebrity status and fundraising activity to gain uncontrolled access to vulnerable people across six decades”. The risk and reward for the abuser in such public concealment is not unusual, after all. If abuse is about power over others, then the abuser’s sense of power is increased as more and more people are deceived. In my book TV FAQ(p.53) I reported an instance of an abuser duping an experienced documentary producer along with the team of therapists advising a 1995 BBC2 series Family Therapy. He was in fact abusing his own daughter. The filming of him and his family in therapy added to the thrill of deceiving the world: it was only after the first week’s filming that his abuse emerged. Savile, by contrast, had a whole adult life enjoying the fact that he was able to dupe all the people all of the time. This was the power and gratification that television gave him. As Channel 4’s Paraic O’Brien put it “It’s about the abuse of power. It is about the tyranny of celebrity. It is about how the weight of a powerful, cleverly-branded persona can steam roll over the weak and vulnerable.”

So how did he achieve this power? There seem to be two reasons. First, Savile shrewdly used the cultural elitism of the BBC management to position himself as a fool who understood ‘the young’. The senior echelons of the BBC long had a distain for popular culture and its proponents. It was all too commercial and crass. Added to this, , ‘contemporary youth’ was profoundly puzzling for the BBC management of the 1970s. Youth styles, music, views and emotions were a world away from those of the generation formed in the 1920s and 30s. Most of the senior management of the BBC probably wished that ‘youth’ would simply go away… or at least grow up. Jimmy Savile seemed to them to be a safe bet: someone who dressed like the young dressed (ie no suit) and appeared to have nothing of the Tin Pan Alley style of an Alan Freeman, nor the pushy cheek of a Simon Dee. Savile was smart enough to offer a solution for the BBC’s youth problem by posing as a harmless fool, a man of the people with no pretensions beyond clowning around and having a good time. He caused no difficulties for management and so they let him get on with it. Crucially, the BBC mistook the adulation for the material being presented by Savile (the music, the unparalled opportunities of Jim’ll Fix It) as adulation for Savile the public figure. For many people watching, Savile was a peculiar being put there by an uncomprehending BBC. Hence the frequent comments now that the scandal has broken: “I never understood the appeal of Savile… he always seemed a bit creepy to me”. Perhaps Savile’s charity work was as much a response to this feeling as it was another route towards gratification of his abuser’s power. For celebrities in trouble, charity work can disarm critics and entrance a whole new public.

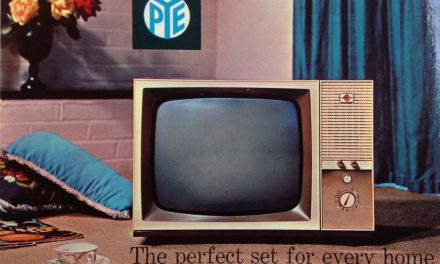

Savile was operating in the TV industry in an earlier era: the era of scarcity. To be on TV was a rare privilege. To many teenagers, just to get your face onto Top of the Pops seemed to be worth a bit of groping. Savile ruthlessly exploited this. This is not only a matter of a different sexual morality, it is a matter of a different culture of celebrity. Hardly anyone could get to appear on TV: Top of the Popsfor half an hour a week was just about the only chance that young people had (unless they appeared in a documentary as an example of a ‘social problem’). So the stakes were high, and the nausea set in only when it was too late. And there was no protection for the young people drawn into Savile’s BBC dressing room. The show depended on unchaperoned young people for its look of authenticity. So there were none of the arrangements long since insisted on by Equity for the protection of professional performers under the age of 16.

Savile’s evil genius was to recognise and exploit these conditions: youth’s hunger for television celebrity and the BBC management’s distain for the popular. Any celebration of television’s history will now have to acknowledge this other side to the power of the medium. And in doing so, it may also acknowledge that whilst television may have changed, the abuse that drove Savile is still with us, and more common that we like to pretend. As Ros Coward concludes: “in certain liberal circles, there’s a belief that paedophilia is “a moral panic”. I meet it all the time in media studies.. When I hear this, I always wonder why people are so keen to close down discussion of abuse. This, after all, is a subject that has taken centuries to dare to speak its name, which is not uncommon, and which has devastating consequences. Sex abuse only seems exaggerated until it affects you or people you know directly, until you see its devastating effect.”

JOHN ELLIS is Professor of Media Arts at Royal Holloway University of London. He is the author of Documentary: Witness and Self-revelation (Routledge 2011), TV FAQ (IB Tauris 2007), Seeing Things (IB Tauris 2000) and Visible Fictions (1984). Between 1982 and 1999 he was an independent producer of TV documentaries through Large Door Productions, working for Channel 4 and BBC. He is chair of the British Universities Film & Video Council and leads the Royal Holloway team working on EUscreen. His publications can be found HERE.