Last Thursday, as I left my house to get the train into my office, I glanced at my phone to see a message from my sister. Whilst this event was in itself not unexpected, the contents of the message was. ‘Bad news,’ it started. ‘Thought you’d want to know that the actor who played Jimmy Corkhill in [UK soap opera] Brookside has died.’ A wave of sadness came over me and, stood alone in the cold on the platform, I quickly checked both the BBC website and social media for confirmation: Dean Sullivan, aka Jimmy Corkhill, had passed away at the age of 68.

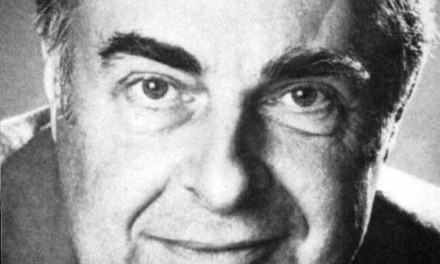

Given that other, more high profile, public figures also had their deaths announced last Thursday, I wouldn’t be surprised if Sullivan’s didn’t register with many UK residents (even less so outside of the country). Despite receiving some extended coverage on both the BBC and ITV’s regional news broadcasts for the North West of England, the loss of a soap actor was one death too many for the UK’s national news agendas that day. Nevertheless, for me, the announcement stung and has stuck with me in the ensuing days. I’d like to take Sullivan’s passing as an opportunity to celebrate his career and share some reflections as to why that may be the case.

Brookside and Sustaining Social Identities

Whilst the small market town in Devon in the South West of England where I grew up was far removed from the city of Liverpool where Brookside was set in myriad ways, the show was nevertheless the soap of choice in our house throughout the 1990s and until its cancellation in 2003. I was first introduced to (or, perhaps, ‘allowed to watch’?) Brookside by my Mum circa 1992. The show quickly became appointment viewing for her, my sister, and me (much to the annoyance of my Dad). Brookside provided us with a shared viewing experience, a point of connection that sustained our family dynamic, and was a continual point for in-jokes, speculation, and, as will shortly become evident, discussing social issues. The social connections that Brookside engendered also extended to friendships, as one of my longest-running male friendships during primary, secondary and tertiary education was with a lad who similarly enjoyed watching the show with his mother.

Jimmy Corkhill quickly became my favourite – if, both at the time and in hindsight, deeply problematic – character. Jimmy was no heroic figure. If anything, Jimmy’s character was quite the opposite of that, and the storylines given to the character provoked more than a few raised eyebrows from my parents. Nevertheless, the affection I had for both Jimmy and the actor who played him has continued to define my identity within my family. Whenever Sullivan made a rare appearance on television in the years following Brookside’s cancellation, I’d be informed of when and where. When the 30th anniversary Brookside: Most Memorable Moments DVD came out in 2012, I excitedly texted my family with news that I’d acquired it and then provided regular updates about revisiting many of Jimmy’s iconic episodes. In short, Jimmy/Sullivan was one of my longstanding TV heroes.

Jimmy Corkhill – The Character

Sullivan/Corkhill first appeared in Brookside in 1986, long before I started watching it. By the time my avid viewing began, Jimmy was an established regular character who (illegally) ran a no frills discount shop on the recently introduced Brookside Parade set (a strip mall with a petrol station opposite; see Figure 2). Jimmy’s character function was less of an antagonist, but more of an irritant to the other, more middle-class and ambitious entrepreneurs servicing the local community, such as Max Farnham (Steven Pinder) and Jimmy’s evergreen nemesis, Ron Dixon (Vince Earl). Jimmy was an underdog, perhaps even ‘Artful Dodger’-esque type, in comparison. This characterization, combined with Sullivan’s ability to either deliver a sarcastic one-liner or point out the pretentiousness of his fellow traders, immediately endeared him to me as a likeable and appealing point of identification.

Yet, Jimmy’s coding as a less-than-legitimate business man, and of a lower social standing than his peers, resulted in the character soon taking a darker and more tragic turn. Jimmy became a drug addict and dealer (cue conversations in the Garner household about ‘appropriate role models’). Then, in a particularly memorable run of episodes, Jimmy was responsible for killing both Frank Rodgers (Peter Christian) and Ron’s son, Tony (Mark Lennock), in a car accident whilst high on cocaine on Frank’s wedding day (cue even more conversations in the Garner household about ‘appropriate role models’).

Towards the end of the 90s, Jimmy got clean, and found redemption as a school teacher – a role which he excelled in – until it was exposed that he’d forged most of his qualifications with the help of a tech-savvy neighbour. Following this, and as UK soap operas became ever-more fascinated with gangsters, Jimmy became a nightclub doorman, relapsed onto drugs, suffered a mental breakdown and an attempted suicide, before being diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Always intertwined with these storylines was Jimmy’s continually strained-yet-loving family relationships, first with his long-suffering wife, Jackie (Sue Jenkins), and then latterly with his daughter Lindsey (Claire Sweeney), who often served as Jimmy’s confident or co-conspirator (especially when the gangster angle took precedent).

A self-designated working class hero, Jimmy’s lower class position within Brookside Close assigned the character an inferiority complex which regularly emerged as a chip on his shoulder. This character trait would always come to the fore when Jimmy came into contact with authority figures. When confronted by a representative of the council planning department about demolishing his self-built ‘Millennium Arch’ art installation, the character attempted to win a reprieve by offering a heartfelt explanation of everything included on it as a celebration of the history and development of Liverpool’s working class culture. Ultimately unsuccessful in his appeal, Jimmy then launched first in to one of his usual passionate tirades, first taking bureaucracy to task, and then turning on one of his neighbours over abandoning their class roots and allowing contemporary global, modern (read American) popular culture to erode that of ordinary working class people.

Jimmy’s rants were always shouted down by his opponents revealing their own working class histories and hardships, meaning that a multi-vocal position towards class identities was articulated throughout the show. Consequently, in scenes where Jimmy’s thoughts on shifting class identities came to the fore, the character’s views would be framed as anything from those of an everyman to a screwball to an out-of-touch dinosaur. Nevertheless, these sequences allude to how Jimmy’s character was frequently employed as Brookside’s mouthpiece for articulating tensions and changes in working class identities and communities against the backdrop of increased social mobility and division, first under Thatcherism and then New Labour. Brookside’s commitment to articulating these complexities continued through to its final episode, and it was no surprise that the show’s epilogue was a lengthy soliloquy on the consequences of the sustained erasure of working class cultures over the show’s 20+ year run, delivered by Jimmy to the younger Nikki Shadwick (Suzanne Collins).

Dean Sullivan as Jimmy Corkhill

Sullivan’s interpretation of Corkhill leaned in to the character’s construction as a chancer, but did so with a breeziness and swagger that enhanced Jimmy’s ‘man of the people’ charm. There was a touch of the ‘Liam Gallagher’ persona to Jimmy, and Sullivan noticeably started using the term ‘Our Kid’ to address people in the mid-90s when Britpop was at its height. These performance qualities, combined with Sullivan’s easy switches from a laid-back vocal delivery style into more strained and exasperated tones when either backed into a corner or realizing the error of his ways, enhanced the character’s appeal, even when the storylines portrayed Jimmy at his absolute worst. For example, during the scene where Jimmy confesses to Jackie about his drug addiction and killing Tony, Sullivan communicated the character’s vulnerability through subtle breaks in his vocal delivery, combined with strained facial expressions and hand gestures to connote the depths of Jimmy’s despair. Yes, the sequence might be indicative of classic soap melodrama in terms of its overwrought emotions, but Sullivan’s performance made you care about Jimmy and his plight despite being a criminal and a murderer.

More often than not, though, Jimmy’s storylines positioned the character in a way that was similar to classic British sitcom characters who, in attempting to escape their assigned class position, would eventually find themselves dragged back to where they started. This construction allowed Sullivan to add great humour to his performances and characterisation, often coming across as a sulky child when his world collapsed around him. The scenes between Jimmy and Jackie following losing his teacher job highlighted these qualities excellently, as Sullivan demonstrated his contempt for his wife through an upturned nose and curt delivery of dialogue. Such techniques captured the sense that, despite Jackie having ended his blossoming educational career by revealing his fake qualifications to a colleague during a jealous outburst, the chemistry and bond between the two characters remained clearly identifiable. Sullivan’s performance as Jimmy during these types of scenes was traceable to the line of tragi-comedy in the UK that dates back to Tony Hancock and Steptoe and Son (1962-74), as the simultaneous warmth and despair arising from the situations continued to shine.

It was this ability to find the light in Jimmy’s circumstances, and fuse this with frustration and vulnerability, that led to Sullivan being Brookside’s longest-running character on Brookside. Sullivan/Corkhill’s importance to the show and popularity was further confirmed in 2003, when he was awarded an Outstanding Achievement Award at the British Soap Awards just as the show itself was ending. It was perhaps unsurprising, then, that Brookside’s concluding shot was a close-up of Jimmy giving one of his usual cheeky winks direct to camera – a reassuring, self-aware nod that, yes, it was sad that the show was ending but that, through Jimmy, the production team knew what they’d achieved.

Postscript

In the years since Brookside’s cancellation, I never had the pleasure of meeting Dean Sullivan. Given its propensity towards using former soap actors when it returned, I kept hoping that a certain popular TV series about a time traveler in a police box might cast him in an episode and that he’d turn up on the convention circuit. Sadly, this never happened.

However, as I started writing this blog, I did start wondering about what Jimmy’s response to a memorial like this might be. Almost immediately, I was reminded of one of the character’s signature lines: ‘Give over, soft lad.’ He’d have been equally embarrassed and proud that someone had thought him worthy of remembering.

Ross Garner is a Senior Lecturer in the spatial and material cultures of media consumption in the School of Journalism, Media, and Culture at Cardiff University. He is currently Co-Investigator on the Media Tourism strand of the UKRI-funded project Media.Cymru.