William Proctor:

One of the first things that came to mind when watching HBO’s Watchmen is whether the series would be as equally impenetrable to audiences that have no experience of the comic. When I pitched the idea for our discussion to Kim Akass, she expressed immediate interest in the hope that it could plug some gaps. Although Kim said that she loves the series, she also admitted that she was experiencing difficulty with making sense of the narrative as a whole as she had not read the comic. But I’m not quite sure if reading the comic would provide the necessary context—it could instead open up a new can of worms! Further, if someone decides to watch Zack Snyder’s adaptation as a crash-course in Watchmen, then that wouldn’t work either as the ending is considerably revised (to the detriment of Snyder’s film I’d argue), and the original ending is instrumental in the HBO series.

Kim said that she ‘can’t get to grips with who is who and the various relationships,’ especially Jeremy Irons’ character. ‘I am sure all will be revealed but I can’t make sense of the space and narrative leaps. But I do love it. It’s really the best TV. But I know I’m missing something.’

I think that’s a fascinating commentary about how tough it can be to follow what is essentially a sequel without knowledge of its antecedent. I can’t help thinking of Robin Nelson’s concept of the ‘flexi-narrative’, a TV series that operates on a fulcrum between self-contained episodes and an overarching mythos, one that allows viewers to jump in-and-out as they see fit. Sit-coms, for instance, are usually flexi-narratives: miss an episode, and you won’t miss that much (although I’d argue that many series require at least some knowledge. I can’t imagine missing episodes of The X-Files, say, especially in the later seasons, and be able to jump back-in without catching up, but maybe that’s my own desire for completion). Conversely, HBO’s Watchmen is in no way a flexi-narrative at all, which is further compounded by the fact that it may not be as accessible to someone who doesn’t have knowledge of the comic book. The fact that various websites have provided primers for Watchmen virgins seems to bear that out, even though I couldn’t imagine reading a news article to bring me up to speed. I wouldn’t be happy with that at all (although I’m speaking personally). If a new series demands that potential viewers need to dash off elsewhere to educate themselves before engaging, then that would seem potentially damaging to me. As Akass said, quite jocularly (but also rightly): ‘it’s like having to read The Irishman before watching the film.’

It’s interesting that HBO’s Watchmen has been critically acclaimed, at least for the most part, and seems to have won over some purists. But at the same time, I wonder if its audiences have all read the comic? I doubt it very much (although that is pure speculation on my part). Still, it’s a risky strategy for HBO, I’d argue, but one that they seem to have pulled off.

What do you think about the series, Will, especially in the context of understanding the story if one has not read the comic? (It is a sequel to the comic, after all, not Snyder’s adaptation.)

Will Brooker:

You raise further interesting issues there. Firstly, the sense that perhaps we can’t directly compare auteurs from different media, or even use the term in the same way across media. Just as Dickens as author means something different from Ford as author, so Moore as author is quite different from Lindelof as author. Moore created the work in collaboration with two other people, plus editors Len Wein and Barbara Kesel, Lindelof’s interviews talk about ‘we’ in a more broadly collective sense. This isn’t just Alan and Dave sharing ideas on a phone call: it’s a corporate storytelling machine. When Lindelof needed to reconcile the fact that Hooded Justice, in one of his few lines of comic book dialogue, stated that the Minutemen should avoid political situations (chapter 2, page 5), even though his HBO version of Hooded Justice is extremely politically motivated, he was able to send a team of writers into a room for days to resolve the issue: they ultimately decided that H.J. was taking a private, satirical dig at his lover Captain Metropolis.

If Moore had encountered that kind of Gordian knot in 1985, he’d have to stomp around Northampton on his own until he untied it, or chat it out with one other guy. So, I think it’s worth bearing in mind that ‘auteur’ means different things in different contexts.

If Moore had encountered that kind of Gordian knot in 1985, he’d have to stomp around Northampton on his own until he untied it, or chat it out with one other guy. So, I think it’s worth bearing in mind that ‘auteur’ means different things in different contexts.

Also, Gray’s ‘interpretation is never finished’ is particularly relevant with regard to Watchmen!

The Hooded Justice episode (‘This Extraordinary Being’) on HBO’s Watchmen is my favourite, but it also enacts a kind of retroactive continuity (or ‘retconning’ in fan vernacular), which is often a risky strategy that risks bating hardcore fans. The concept of retconning originated as a comic book term, but has since been mobilized in more mainstream contexts over the past decade or so (as has the concept of rebooting). In essence, retconning refers to ‘a new piece of information that imposes a different interpretation on previously described events’ (although there are different types of retconning too!)

In the comic, Hooded Justice is the first costumed ‘hero,’ but we don’t learn that much about his background beyond that. In the HBO series, we are given Hooded Justice’s origin story, one which is imbued with racial politics very much beyond what Moore intended (or at least, what Moore revealed in the comic). I think this episode is quite audacious in revisionist terms. In Lindelof’s treatment, Hooded Justice is the nom de guerre of Will Reeves, a black police officer who dons a hood, beneath which a noose is tied around his neck to symbolize a lynching that the character had experienced at the hands of his fellow police officers. We are informed that Reeves wears the hood to disguise his racial identity—one particularly charged comment in the episode includes Reeves’ wife telling him forcefully that he won’t be able to effect change ‘as a black man.’ So, the hood is basically employed to hide Reeves’ face during an era when a black superhero would not be acceptable. The majority of the episode is in flashback mode after Angela Abar overdoses on her grandfather’s ‘Nostalgia’ pills, a psychoactive drug made from ‘synthetic mnemonic material’ that, when taken, provides access to past memories (although dosing oneself with another person’s memories is dangerous, as explained in the episode). In other words, Angela ends up tripping on her grandfather’s synthetic memories.

It’s the most daring, courageous episode of the series, I’d argue. Firstly, by explaining the Hooded Justice’s back-story, and revealing the character to be black, radically shifts and ‘refocalizes’ how we read the comic book (or at least, it did for me). From this perspective, HBO’s Watchmen also operates as paratext, encouraging a re-reading and re-interpretation of events in the comic (whether that’s a good or bad thing is a different question). This retconning could certainly be viewed by Watchmen fans as playing with Moore’s authorial intent too much, however. Although we learn little about Hooded Justice in the comic, it seems that Moore intended the character to be emblematic of white supremacy. In the comic, Hollis Mason states that the masked heroes were often ‘politically extreme,’ and that he’d heard Hooded Justice ‘openly expressing approval for the activities of Hitler’s Third Reich.’ Lindelof could easily claim that that was Will Reeves throwing people off the scent.

On the one hand, the episode seems to have made its mark in entertainment criticism as ‘one of the most explosive episodes on TV this year.’ On the other, there have been some critical detractors: Wired’s Matt Kamen, for instance, writes that ‘HBO’s Watchmen Totally Misses the Point of ‘Watchmen’; while Kevin Fallon of Daily Beast focuses on the disparity between critics and fans, with the latter ‘review-bombing’ the series on Rotten Tomatoes for its ‘woke propaganda’. As one fan stated: “They took everything that was good about Watchmen and Rorschach, then defectated [sic] all over it Last Jedi style. This isn’t Watchmen, it’s Wokemen, sorry, Wokepersons.” Unfortunately, this kind of fan discourse is common-place nowadays, if indeed such comments come from actual fans, or trolls out for ‘the lulz’ (how would we know in any case?). ‘Somehow a show about gritty heroes became another show pandering to the SJWS [social justice warriors] of the world and inciting race divide and preaching an agenda,’ wrote another.

Secondly, while the comic’s dramatis personae is largely white, race and ‘blackness’ become the centerpiece of the series. The fact that Lindelof is white himself has not gone unnoticed, yet he has been quite open about how uncomfortable he felt commenting on black lives and black experiences, fictional though they are, so much so that he argued that his writers’ room needed to be ethnically diverse. (Although it was Lindelof who originated the idea that Hooded Justice is black, it was the co-writer on the episode, Cord Jefferson, who came up with the lynching element.) I find it interesting that the series’ focus on racial politics and social justice is paralleled by producers thinking about the politics of its creative staff. All in all, this episode was the most enthralling for me.

Will Brooker:

I agree that our interpretation of a text changes throughout our lives, as the intertexts and frameworks around it evolve and shift. If I turned back to Watchmen now, I might find it hard not to imagine Hooded Justice as Will Reeves, and Lindelof’s final episode has now retroactively inserted Bian, Lady Trieu’s mother, somewhere in the Karnak scenes. Retcons like this, unless we resist them, alter previously existing texts in a form of time travel: I always think of Geoff Klock’s example in How To Read Superhero Comics and Why that when Frank Miller showed Batman wearing armour plating under his yellow chest insignia in 1986, immediately Batman had always been wearing armour plating there, in every earlier story.

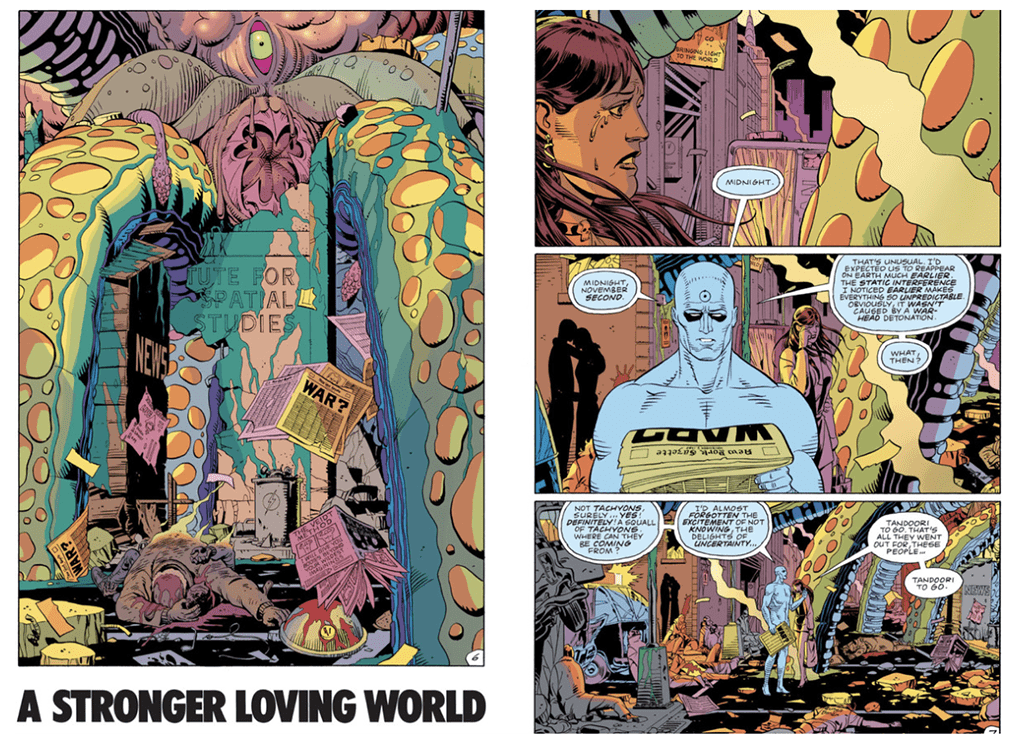

Returning to how HBO’s Watchmen follows the comic, I was struck by how little it offered at first in terms of background: it plunges us right in with mostly new characters and situations. The Watchmen Watch podcast perceptively noted that the TV series starts off some distance from the original material, then moves steadily back towards it, whereas many spin-offs work in the opposite direction, beginning in safer, more familiar territory and then forging in their own direction. I think Dr Manhattan’s origin at Gila Flats is first obliquely referenced in episode 2, then Laurie enters in episode 3 and we learn briefly, through dialogue, about her history with Nite Owl and the other former Crimebusters. Rorschach is mentioned by Agent Petey during an FBI meeting, and brushed away with a dismissive remark about how it’s not the 80s anymore. In episode 5 of 9 we finally witness the squid attack, through Wade’s flashback, and with him, we learn the truth about Veidt’s scheme. Episode 6 returns us to the Minutemen, whom we’ve glimpsed fleetingly in the American Hero Story show-within-a-show, and 8 gives us a history of Dr Manhattan for the first time. Other key aspects of Watchmen, like the death of the Comedian and Rorschach’s investigation, which prompt and drive the original plot respectively, barely feature. And Ozymandias’ storyline is treated as a sideline for most of the series, almost functioning as a show-within-a-show itself: a manor house farce set millions of miles away.

Lindelof explained in a recent interview that he watches the series with his wife Heidi, who doesn’t know the comic book, and that while she admits there are ‘insider’ details that pass her by, ‘the fundamental math of the show and what you’re supposed to care about played for her.’ I was surprised by how little the HBO Watchmen briefed viewers about the original, but perhaps it gave them what they needed, just when they needed it, telling them about Dr Manhattan only when he was about to appear on-screen, and so on. I’m not in a position to judge how well it works for them, as the comic is like an old friend to me, but I’d suggest that the show’s main point of entry is Angela Abar, an entirely new character, and that becoming involved in her story doesn’t depend on us knowing what happened thirty-four years earlier. HBO’s Watchmen tells us about the White Night murders of 2016 long before it reveals the events of 1985, because that trauma shaped Angela far more than the squid attack. It drops information when it becomes relevant. There are also a lot of nice in-jokes and quotations for the Watchmen fan — in the last episode, for instance, Jon was repeating lines directly from the comic as he lost sense of time — and of course the supporting paratexts like Peteypedia offer more Easter Eggs for the devotee.

Lindelof explained in a recent interview that he watches the series with his wife Heidi, who doesn’t know the comic book, and that while she admits there are ‘insider’ details that pass her by, ‘the fundamental math of the show and what you’re supposed to care about played for her.’ I was surprised by how little the HBO Watchmen briefed viewers about the original, but perhaps it gave them what they needed, just when they needed it, telling them about Dr Manhattan only when he was about to appear on-screen, and so on. I’m not in a position to judge how well it works for them, as the comic is like an old friend to me, but I’d suggest that the show’s main point of entry is Angela Abar, an entirely new character, and that becoming involved in her story doesn’t depend on us knowing what happened thirty-four years earlier. HBO’s Watchmen tells us about the White Night murders of 2016 long before it reveals the events of 1985, because that trauma shaped Angela far more than the squid attack. It drops information when it becomes relevant. There are also a lot of nice in-jokes and quotations for the Watchmen fan — in the last episode, for instance, Jon was repeating lines directly from the comic as he lost sense of time — and of course the supporting paratexts like Peteypedia offer more Easter Eggs for the devotee.

At this stage I’ll ask you a question. During our discussion, the finale was released. Has your view of the HBO series changed now it’s complete?

For my part, on reflection, I think the final episode was weaker than the preceding ones, and that it perhaps weakened the series as a whole. I’ve been thinking about my issues with it, and some of them, to be fair, are exactly the same as my problems with Watchmen’s plot and tone. Lindelof says in an interview that when they started planning the sequel — again, this sense of a collective authorship — they listed what they loved about the graphic novel, and one of the key points was its slow transition from gritty, street-level noir investigation to fully-fledged science fiction crisis by episode 12. That’s a shift I’ve always been unhappy with since 1986. I find the last episode less engaging because of its huge scale and fantastical elements. On the early pages of issue 1’s script, we have Moore asking Gibbons if he can make it look as though Rorschach is really straining to pull himself up the building, to avoid Batman cliché. The whole project of Watchmen is meant to undermine and challenge superhero tropes, and to ask how all of this would work in the real world. Then in the last issue, we have an actual giant squid smashing through New York City. After the tight grid storytelling where action scenes remain on the low-key level of two guys entering a bar and breaking a little finger across two panels, we now have splash pages of garish tentacles and sprawled bodies, and a grand plan based on teleportation and psychic abilities. It all felt a little broad and on the borders of silliness to me.

Equally, the revelation in HBO’s Watchmen finale that the Millennium Clock is essentially a big laser to suck up Dr Manhattan’s power, combined with the pseudo-science about synthetic lithium and again, teleportation, seemed disappointingly daft. I felt the CGI looked cheaper this episode too, as if the entire budget had been spent weeks earlier, on the squid itself — which was an incredible spectacle, superior to its comic book incarnation — and the visuals often reminded me of Doctor Who.

Adrian Veidt’s story had been kept separate to the main plot so far, and when he joined the other characters, he seemed a jarring element, almost from another genre. The series had evolved him into a comedy character — his adventures on Europa become Monty Pythonesque — which again weakened the tone of the dramatic climax. I think it’s reasonable for a sequel to have its own distinct take on the original cast, and the way Laurie had changed was plausible, but to have Ozymandias knocked out by a cop with a wrench, when the graphic novel shows him dealing effortlessly with Rorschach’s attacks from behind, was throwaway slapstick.

Adrian Veidt’s story had been kept separate to the main plot so far, and when he joined the other characters, he seemed a jarring element, almost from another genre. The series had evolved him into a comedy character — his adventures on Europa become Monty Pythonesque — which again weakened the tone of the dramatic climax. I think it’s reasonable for a sequel to have its own distinct take on the original cast, and the way Laurie had changed was plausible, but to have Ozymandias knocked out by a cop with a wrench, when the graphic novel shows him dealing effortlessly with Rorschach’s attacks from behind, was throwaway slapstick.

I also felt that having this semi-competent old white man, who’s been exposed not just as physically clumsy but also naive and foolish, saving the world again, struck a strange note after Lady Trieu’s speech about white supremacy, and the series’ bold focus on Black trauma, history and heroism. After recasting both the first superhero and the first godlike being as African-American, why have Veidt, Laurie Blake and Wade, all of whom are white, providing the solution to the problem while Angela Abar is left helplessly scrambling for shelter in Tulsa, with nothing useful to do? After the subplot about Lady Trieu’s mother stealing Veidt’s semen and giving birth to a genius daughter — a plan that worked partly because she, as a Vietnamese cleaner, was invisible to his own white supremacist viewpoint — why portray her so unambiguously as the villain and immediately destroy her? Didn’t she possibly have a different perspective to offer, with the possibility of bringing a new, alternative utopia? And if the moral of Watchmen — the graphic novel and TV show — is that masks are dangerous, and that anyone seeking absolute power is morally questionable, why wasn’t there a greater sense of foreboding around the idea that Angela could take on all of Dr Manhattan’s abilities? Are we meant to assume that Veidt and Trieu are dangerous narcissists, but that Angela would, exceptionally, be a ‘good’ kind of all-powerful being, who would change the world wisely?

I also felt that having this semi-competent old white man, who’s been exposed not just as physically clumsy but also naive and foolish, saving the world again, struck a strange note after Lady Trieu’s speech about white supremacy, and the series’ bold focus on Black trauma, history and heroism. After recasting both the first superhero and the first godlike being as African-American, why have Veidt, Laurie Blake and Wade, all of whom are white, providing the solution to the problem while Angela Abar is left helplessly scrambling for shelter in Tulsa, with nothing useful to do? After the subplot about Lady Trieu’s mother stealing Veidt’s semen and giving birth to a genius daughter — a plan that worked partly because she, as a Vietnamese cleaner, was invisible to his own white supremacist viewpoint — why portray her so unambiguously as the villain and immediately destroy her? Didn’t she possibly have a different perspective to offer, with the possibility of bringing a new, alternative utopia? And if the moral of Watchmen — the graphic novel and TV show — is that masks are dangerous, and that anyone seeking absolute power is morally questionable, why wasn’t there a greater sense of foreboding around the idea that Angela could take on all of Dr Manhattan’s abilities? Are we meant to assume that Veidt and Trieu are dangerous narcissists, but that Angela would, exceptionally, be a ‘good’ kind of all-powerful being, who would change the world wisely?

The ending of Watchmen, the graphic novel, is disturbing and powerful in my opinion because the villain wins, and most of the heroes agree to stay silent about his act of mass murder: it’s a happy ending built on lies and death, ending with the threat of instability as Seymour reaches for the diary that could expose Veidt’s plan. The ending of HBO’s Watchmen seemed simply to imply that the right person was going to get powers, and in some way be reunited or connected with the spirit of her beloved Jon. Trieu is dead, Veidt is going to jail, the 7th Kavalry are wiped out. Despite the cliffhanger, it seems that everything is resolved; the bad guys are gone, and a new hero is about to be born.

So, I enjoyed the last episode less than the others, and looking back at it, I feel it was a slightly disappointing finale for those reasons. What are your thoughts?

William Proctor:

Now that it’s ‘complete’, I find myself wanting to re-watch it again now that I know where it ends up, but I mainly agree with your points. While I accept that having Ozymandias/ Adrian Veidt ‘save the day’ once again is extremely problematic, especially given the racial politics of the series, I wonder if that’s the point in a sense: that Veidt is instrumental in the conclusion when we know he is really a narcissist, more awed by his own self-importance and ego than in saving people. In many ways, Veidt is the antithetical superhero, but he’s not quite a supervillain either (or is he?). Then again, it seems that the series echoes the comic with Veidt’s actions in the finale. He remains a complex character though, I’d argue. Unlike Doomsday Clock, which shows that Veidt’s scheme from the ending of the comic has been exposed from the off, the HBO series’ trajectory keeps it uncovered for the most part— although it is eventually revealed to Looking Glass, and members of the 7th Kavalry have full knowledge of it, as does Angela Abar. In the series, Veidt’s conspiracy, revealed at the end of the comic, does seem to have ‘saved the world’, as he intended. Of course, viewers not familiar with the comic may not know that!

You’re right to say that as the series progresses, there are more substantive narrative links to the comic, and I agree with your assessment that this is a kind of reversal to what we might expect. But I also think that the final two episodes massively undermine what came before. The focus on an incognito Dr Manhattan revealing himself to the viewer as Angela Abar’s husband, literally hiding in human skin, seems rather hackneyed to me. I just couldn’t buy it. For all Lindelof’s authorial bravura throughout the series, I felt that the latter episodes looked back to the comic far too much for inspiration, and ended up with what I feared most of all when the series was announced: that it would be too beholden to the comic, and wouldn’t be able to chart its own path without becoming swallowed up by the comic’s cultural shadow. Of course, that’s to be expected in many ways, but I can’t help thinking that the series’ end seriously compromises—or even sabotages— what Lindelof and his creative team had accomplished throughout. I still think it’s a good series, but I’m sorely disappointed with where we ended up. It seems that there aren’t that many creators that feel a superhero show can do without daft, absurd endings. For all the talk about superhero realism, even Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins and The Dark Knight have their hokey, fantastic elements.

You’re right to say that as the series progresses, there are more substantive narrative links to the comic, and I agree with your assessment that this is a kind of reversal to what we might expect. But I also think that the final two episodes massively undermine what came before. The focus on an incognito Dr Manhattan revealing himself to the viewer as Angela Abar’s husband, literally hiding in human skin, seems rather hackneyed to me. I just couldn’t buy it. For all Lindelof’s authorial bravura throughout the series, I felt that the latter episodes looked back to the comic far too much for inspiration, and ended up with what I feared most of all when the series was announced: that it would be too beholden to the comic, and wouldn’t be able to chart its own path without becoming swallowed up by the comic’s cultural shadow. Of course, that’s to be expected in many ways, but I can’t help thinking that the series’ end seriously compromises—or even sabotages— what Lindelof and his creative team had accomplished throughout. I still think it’s a good series, but I’m sorely disappointed with where we ended up. It seems that there aren’t that many creators that feel a superhero show can do without daft, absurd endings. For all the talk about superhero realism, even Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins and The Dark Knight have their hokey, fantastic elements.

Will Brooker is Professor of Film and Cultural Studies and Head of the Film and Television Department at Kingston University, London. Professor Brooker’s work primarily studies popular cinema within its cultural context, situating it historically and in relation to surrounding forms such as literature, comic books, video games, television and journalism. In addition to the numerous essays and articles on film and fan culture that he has published, his books include Why Bowie Matters (2019), Forever Stardust: David Bowie across the Universe (2017), Star Wars (2009), Alice’s adventures: Lewis Carroll in popular culture (2004), Using the Force: Creativity, Community and Star Wars Fans (2002), and the edited anthologies The Blade Runner Experience (2004) and The Audience Studies Reader (2003). He is also a leading academic expert on Batman and the author/editor of several books on the topic, including Batman Unmasked (2000) Hunting the Dark Knight (2012), Many More Lives of the Batman (2015).

William Proctor is Principal Lecture in Film and Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He is co-editor on the books, Global Convergence Cultures: Transmedia Earth (with Matthew Freeman, for Routledge 2018), and Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion and Reception (with Richard McCulloch, for University of Iowa Press, 2019). William is a leading expert on reboots, and is currently writing a monograph on the topic for Palgrave titled Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia. He has published on a wide-range of topics, including Star Wars, Batman, James Bond, Stephen King, and more.