The twentieth century began with utopia and ended with nostalgia.

—Author, cultural theorist, and artist, Svetlana Boym (2007: 7)

It’s impossible to overstate how original the Beatles looked and sounded when they seemingly arrived out of nowhere during the early Sixties. The first 11 minutes of Peter Jackson’s 7-hour 48-minute documentary miniseries, The Beatles: Get Back, which debuted 25-27 November 2021 on Disney+, succinctly recounts the group’s meteoric rise and mind-blowing metamorphosis from a boy band brimming with mod innocence and optimism to a world-weary quartet nearing the end of their run as a creative ensemble.

In 2017, executives at Apple Corp Ltd. invited Jackson, the celebrated New Zealand-based director, to revisit the 60 hours of footage and 150 hours of audio recordings from the January 1969 ‘Get Back sessions’ in order to recover and refurbish this old material in much the same way that he and his longtime collaborators at WingNut Films had done in producing the World War I documentary, They Shall Not Grow Old (2018).

The original 16 mm. footage and accompanying sound was recorded by director Michael Lindsay-Hogg and his crew members over 22 work days during January 1969. What resulted over four years is a meticulous digitized reconstruction by Jackson and his close-knit group of creative associates. The Beatles: Get Back is a pristine 21st century restoration that has once again thrust the band front and center along with the decade that shaped them and they helped define.

The comparative-historical sociologist, Eleanor Townsley, refers to the Sixties in hindsight as a ‘trope’ that ‘denotes a definitive break between “then” and “now.”’ She classifies the Sixties as an ‘originary point’ that identifies ‘a break or major change . . . after which nothing is the same’ (Townsley, 2001: 105-106). In rock ‘n’ roll history, specifically, the Beatles and their music mark a before and after point of no return. Together they experienced a lifetime of change throughout the decade even though Ringo and John were still only 28, Paul 27, and George 25 by the time of the ‘Get Back session.’

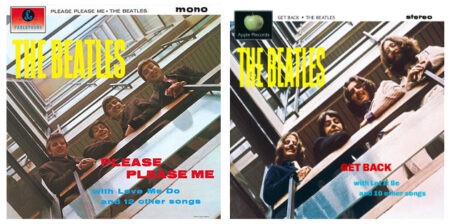

Photographer Angus McBean took the famous stairwell cover shot of the Beatles in mid-February 1963 at the EMI House on 20 Manchester Square in central London for their debut UK LP, Please Please Me. He reprised the shot at the suggestion of John Lennon some six years later on 13 May 1969 for what would be the long delayed Get Back album, later issued as Let It Be on 8 May 1970. These ‘before’ and ‘after’ images were again used on the covers of the compilation ‘Red Album’ (The Beatles/1962-1966) and ‘Blue Album’ (The Beatles/1967-1970), both issued 2 April 1973.

Understandably, Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 81-minute documentary, Let It Be (1970), is now being compared unfavorably to The Beatles: Get Back. Still, the fact is these two films have little in common in terms of purpose and style besides being edited from the same ‘Get Back’ source material. All of the Beatles knew Lindsay-Hogg, first, as a house director at the British pop music programme, Ready Steady Go! (1963-66); and later as the director of several of their pioneering promotional films such as ‘Paperback Writer’ (April 1966) and ‘Hey Jude’ (August 1968). He thus was brought on board to shoot and record the band’s next project.

Having just wrapped the intense five-month recording sessions for The White Album in October 1968, Paul McCartney suggested to the other Beatles that they return to their roots as a rock ‘n’ roll band for their next album. Head of Apple Films, Denis O’Dell followed up on McCartney’s lead recommending they film a ‘Beatles at work’ television documentary of the band creating their next LP culminating in a live performance of new songs.

Consequently, the broad outline of what they called the ‘Get Back sessions’ was born. ‘Musically we never let each other down,’ recalls Ringo Starr. ‘We’d make a record . . . and be relaxing and the phone would ring and we would know by the ring: it was Paul. And he’d say, “Hey, lads you want to go into the studio?” If it hadn’t been for him, we’d probably have made three albums, because we all got involved in substance abuse, and we wanted to relax’ (Remnick, 2021:47).

Since Ringo had already committed to co-starring in The Magic Christian (1969), which was set to start shooting at Twickenham Film Studio in February 1969, the Beatles commenced work there on 2 January 1969, moving to what was a makeshift studio in the basement of the Apple Building in London halfway through the recording session on January 15. Lindsay-Hogg and crew ended all their filming and recording on the ‘Get Back’ project on 31 January 1969.

In retrospect, the ‘Get Back sessions’ were never turned into the originally intended TV special. What resulted is a repurposed performance piece where the emphasis is on the Beatles composing, rehearsing, and performing, leading up to an abridged version of their rooftop concert, which lasts only 23 minutes (instead of the actual 42 minutes) although this sequence amounts to more than one-quarter of the release print of Let It Be. The album of the same name was released on 8 May 1970.

Consistent with Lindsay-Hogg’s previous contract work for the band, his barely feature-length documentary is intended to be an extended promotional film for the companion LP as it debuted in US theaters on May 13 and then in the UK on May 20. The film also was a way of clearing the decks at Apple. It was previously handed over to United Artists in the spring of 1970 to complete a three-picture deal struck by Brian Epstein back in 1964 beginning with A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and later Help! (1965).

Let It Be’s cinema vérité aesthetics are washed-out, grainy, and low contrast even by 1969-70’s standards since the original 16 mm. footage had to be blown up to 35 mm. for theatrical exhibition. The fly-on-the-wall perspective also eschews any kind of deeper character development to focus primarily on the Beatles making music, which they appear to be enjoying as in their genetically related portrayal in The Beatles: Get Back.

The little character work that does survive Let It Be’s final cut shows Yoko Ono mostly dour and disinterested in the dozen or so cutaways of her, for example, while John for his part is seen as either bored or spaced-out when not playing an instrument or singing. Lindsay-Hogg moreover gives the quarrel between Paul and George special emphasis in the first act of Let It Be (from 15:30 to 16:45) to provide a dramatic lift, although the fact that George actually leaves the band for a few days is never directly revealed in the film.

The reception to both the film and album, Let It Be, was mixed in the wake of Paul McCartney’s 10 April 1970 public pronouncement that the Beatles had broken up. McCartney’s announcement actually came nearly seven months after the Beatles had ceased being a band when John Lennon announced, ‘I’m leaving,’ during a heated business meeting at the Apple Building on 16 September 1969 (Remnick, 2021: 47; McCartney, 2021: 111). All three other Beatles had briefly left the group before: Paul during Revolver (1966); Ringo The White Album (1968); and as noted, George during the ‘Get Back sessions.’ This time it was official, however; the quixotic promise the Beatles once represented as a band was now a vestige of the Sixties.

‘The four of them had gone through this mammoth experience, from when they were unknown, to being four of the most famous people in the world,’ observes recording engineer and coproducer, Glyn Johns, who is featured prominently in The Beatles: Get Back. ‘The fact that George left the band is no different from any other band I ever worked with . . . There was this massive bond between them. They were like family, really’ (Williams, 2021).

For literally hundreds of millions of fans past and present, the Beatles never actually went away. The popularity of their music has ebbed and flowed over the years but the band has always maintained its artistic and cultural appeal. Peter Jackson’s miniseries reintroduces the group anew to Disney+’s 118.1 million worldwide subscribers. The Beatles: Get Back proved to be a top-10 original breakout hit within the streaming sector of the global television industry, predictably skewing slightly towards baby boomer and millennial viewers (Maglio, 2021).

21st century audiences are once again able to ‘Meet the Beatles!’—only this time in full-coloured, high-definition imagery complemented by brilliant high-resolution sound. The Beatles: Get Back’s concise introduction begins with them arriving in Hamburg as an unknown and largely amateurish quintet (Pete Best, George Harrison, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Stuart Sutcliffe) on 17 August 1960.

Two years and two months later on 17 October 1962, the fast-evolving preternaturally talented Fab Four (Harrison, Lennon, McCartney, and Ringo Starr) reached the UK charts for the first time with ‘Love Me Do,’ peaking at number 17; followed by three successive number 1 hits throughout the rest of 1963 with ‘From Me to You’ (April 24), ‘She Loves You’ (September 4), and ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ (December 11).

America’s foremost TV impresario, Ed Sullivan, first spotted the band while touring England that autumn just as Beatlemania was flowering. Sullivan signed the band for three upcoming appearances (two live and one taped) on his eponymously named show for $75,000 or roughly one-half of what he paid Elvis back in 1956-57. The amount was still a princely fee for the fresh-faced Beatles and their young manager, Brian Epstein, who eagerly agreed.

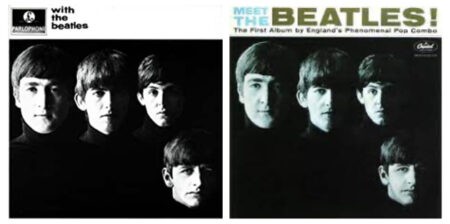

The Beatles second studio album, With the Beatles, was released by Parlophone in the UK on 22 November 1963. The cover featured a cameo shot of John, George, Paul, and Ringo by fashion photographer, Robert Freeman. The album was retitled, Meet the Beatles, and was released by Capitol in the US on 20 January 1964. A blue tint was added to the original black-and-white photograph of what would become Freeman’s iconic portrait.

No one could have predicted that the Beatles would draw an audience of nearly 74 million for their US television premiere on 9 February 1964; combined with 71 million more viewers a week later on February 16. These two appearances marked the first and third highest-rated US TV programs of the entire decade. The charming exuberant Beatles alongside the stiff round-shouldered Sullivan presented an obvious clash of generational styles and sensibilities.

The Beatles initially appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show (CBS, 1948-1971) on 9 February 1964 before a live TV audience of 74 million viewers. Sullivan is shown below trying to quiet his studio audience. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and historian, David Halberstam, described Ed Sullivan as ‘the unofficial Minister of Culture in America’ who weekly hosted the biggest acts in show business for nearly a quarter century (1993: 475)

The Beatles surrounded Ed Sullivan with their slightly deviant hairstyles, Pierre Cardin collarless jackets, and Cuban high-heeled boots. Their personal charm radiated outward, complementing their jamais vu (familiar yet different) sound. As smartly dressed, well mannered, and benign as they looked on nationwide television, the Beatles provided viewers with a glimpse of a youthful counterculture that was rapidly emerging throughout Europe and North America.

The Beatles were sui generis 60 years ago embodying the promise of a better tomorrow. Certainly that utopian rose-colored aura of hope and possibility remains part of their continuing appeal today for both viewers who remember them from way back when as well as those who never experienced them firsthand but still feel nostalgic about what they once represented. Even a filmed portrait of John, Paul, George, and Ringo winding down as a working band in The Beatles: Get Back is subject to rosy retrospection for a mass worldwide audience viewing them online in 20/20 hindsight.

A half-century after the ‘Get Back sessions,’ it doesn’t matter much anymore why the Beatles broke up. Many theories abound: the leadership void created by Brian Epstein’s untimely accidental death at 32 from a drug overdose on 27 August 1967; the pressures of the music industry; their nonstop production schedule; Paul’s relentless work ethic and sometimes bossiness; Yoko Ono’s constant presence in the recording studio; John (and Yoko)’s self-admitted heroin addiction; John and Paul’s mild condescension towards George and their dismissal of his songwriting abilities; each of the Beatles going his own way in his private life; and the list goes on.

Suffice it to say, their breakup was caused by a constellation of factors. Renaming the ‘Get Back sessions’ Let It Be indicates a prescient and welcome realization by all involved that the end was near. Paul McCartney is clearly the most invested in keeping the band together throughout The Beatles: Get Back. ‘It took a while,’ McCartney now admits, ‘but I suppose I eventually got with the programme’ (McCartney, 2021: 193).

The most poignant insight in The Beatles: Get Back is that John, Paul, George, and Ringo obviously love each other; and they are creatively connected even as they are coming undone as a group onscreen. The experience of viewing the entire miniseries simulates spending a month in the recording studio with the band. Past becomes present, providing a privileged, partial, and material record of the inner workings of arguably the most significant and influential rock ‘n’ roll band of all-time.

Overall, they play approximately 125 songs of which 75 are original compositions from albums past, present, and future, including Abbey Road (released 26 September 1969) as well as each member’s first post-Beatles solo album beginning with Ringo’s Sentimental Journey (27 March 1970), Paul’s McCartney (17 April 1970), George’s 3-disc All Things Must Pass (27 November 1970), and John’s Plastic Ono Band (11 December 1970). The LP, Let It Be, thus had much in-house competition from Apple Records in the pop music marketplace upon its release in early May 1970.

The Beatles musical tastes beyond their own work are expansive and eclectic, from Chuck Berry to Samuel Barber, Hank Williams to Irving Berlin. They play 50 songs or snippets across a number of genres from a wide range of other composers who are inspiring and influencing them in the moment as they try to write an album’s worth of music under their own arbitrarily short self-imposed deadline.

Watching the band’s painstakingly slow creative process unfold is probably the most valuable takeaway in The Beatles: Get Back, and to a lesser degree, Let It Be. For instance, seeing and hearing Paul McCartney struggle in real time to compose ‘Get Back,’ switching his chord patterns on his electric bass as if it was a lead guitar when he’s liking what he’s singing more than what he’s playing is a revelation.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=rUvZA5AYhB4

Capturing the creative process in action has been notoriously elusive throughout the history of moving imagery and recorded sound. The Beatles: Get Back in particular portrays the band as fully immersed in the creative process—playing, joking, arguing, improvising—and above all, collaborating at this unique moment of its slow interpersonal unravelling.

Moreover, The Beatles: Get Back and Let It Be together offer quotidian onscreen representations of the ‘Beatles at work’ in two distinct and highly subjective screen versions of the ‘Get Back sessions’ providing concrete evidence of the band overcoming its own internal creative challenges by still producing memorable music at a stressful and turbulent period in its history.

Gary R. Edgerton is Professor of Creative Media and Entertainment at Butler University. He has published twelve books and more than ninety essays on a variety of television, film and culture topics in a wide assortment of books, scholarly journals, and encyclopedias. He also coedits the Journal of Popular Film and Television.

References

The Beatles: Get Back (2021) Disney+. Apple Corps Ltd./Wingnut Films, 468 minutes (Part 1: 157 minutes; Part 2: 173 minutes; and Part 3: 138 minutes).

Boym S (2007) Nostalgia and Its Discontents. The Hedgehog Review 9(2): 7-18.

The Ed Sullivan Show (1948-71) Sullivan Productions/CBS Productions/CBS.

Halberstam D (1993) The Fifties. New York: Fawcett Books.

McCartney P (2021) The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present. Edited with an Introduction by Paul Muldoon. New York: Liveright.

Let It Be (1970) United Artists. Apple Films/ABKCO Industries, 81 minutes.

Maglio T (2021) ‘The Beatles: Get Back’ Bowed with Majority of Audience Over 55, According to Nielsen. The Wrap, 27 December. Available at https://thewrap.com/the-beatles-get-back-ratings/.

Ready Steady Go! (1963-66) Associated Rediffusion/ITV.

Remnick D (2021) Let the Record Show: Paul McCartney’s Long and Winding Road. The New Yorker, 18 October: 40-51.

Townsley E (2001) The Sixties’ Trope. Theory, Culture & Society 18(6): 99-123.

Williams A (2021) The Epitome of British Rocker Cool. New York Times, 12 December: ST4.

![FOR[E] SHADOWING: INTERTEXTUALITY BETWEEN SUCCESSION SERIES THREE AND WHAT WE DO IN THE SHADOWS SERIES FOUR by Melissa Beattie](https://cstonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Untitled-440x264.jpg)