Though not well-studied academically,[1] the NBC series Heroes (2006-2010; 2015) is notable for many reasons. The series brings up a number of topics with regard to quality TV, serialisation, paratexts and the construction/deconstruction of (anti-)heroes, though I want to focus on an aspect of the text which has not been prominently addressed but which is relevant to a number of representational issues: that of the series’ engagement with the zombie myth.

For those unfamiliar with Heroes, it follows an ever-expanding group of characters who develop, study and/or attempt to control various types of superpowers and the people who have them. Heroes engages explicitly with Japanese culture and history through the character of Hiro Nakamura (Masi Oka), which is no doubt why much of the work on the series’ portrayals of international characters focuses upon him (e.g., Chan 2011). But there is a far more subtle engagement of culture and myth in the series and, like Hiro’s arc, it serves in many respects to subvert and/or problematise cultural stereotypes whilst also engaging in some sociocultural critique. I am referring, of course, to the character commonly referred to as ‘the Haitian’ (Jimmy Jean-Louis) before his actual name, René, was revealed in later series.

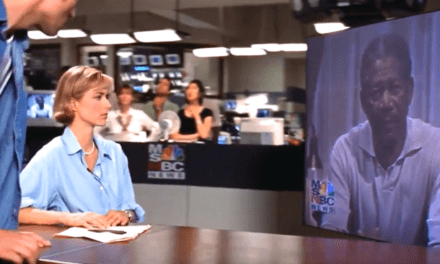

On the face of it, naming a character as ‘the [nationality]’ can be read as reductive and, indeed, in the early episodes of series one the Haitian never speaks, only silently follows orders as he erases memories of those deemed to be risks to the shadowy government agency who employs and controls him. Both the depersonalisation and the abilities he has – and the long-term effects on those he repeatedly erases relate to other memory problems – evoke the particularly Haitian-associated myth of the zombie. Garland (2015) states that transnational decontextualisation means that ‘the contemporary cinematic zombie has been largely divorced for much of its life from its Haitian origins’ (Garland 2015: 273), with Hoermann (2017) going further, stating that:

whereas horror and terror are associated with the zombie from its inception, it is only with the US occupation of Haiti (1915–1934) that US-American writers and directors invented the zombie of popular North Atlantic culture: a soulless slave without consciousness directed by a zombie master. …this amounts to a neo-colonialist act of symbolic re-enslavement of the self-emancipated Haitians. This time they are deprived not merely of their freedom as under the slave regime, but even of their consciousness (Hoermann 2017: 152).

Thomas (2010: 2) states that ‘…zombification practices would find expression in discourse associated with compromised subjectivities that resulted from imperialism and slavery.’ However, as she later discusses with regard to literature, the zombie is vastly more nuanced than this simplified summary, the two elements of imperialism and (ex-)slavery/control are apparent, albeit unremarked upon, in the Haitian’s storyline. Potter (2009) notes that zombies are a common metonym for Haiti in American news coverage; all of this implies that a similar metonymy can be read here with all its connotations.

As noted above, the character initially functioned as a silent enforcer, working with Noah Bennet, aka ‘HRG’ (Jack Coleman),[2] to find and control those with powers. Like HRG, however, the Haitian has a fundamental moral disagreement with those who control him which leads to his refusal to erase HRG’s daughter Claire’s (Hayden Panettiere) memory.[3] This illustrates his conflicted and compromised subjectivity that Thomas (2010) connects with the zombie myth. But it also is the first step towards both his and HRG’s aligned redemption arcs against their employers. However, the Haitian’s storyline also connects his first act of (televised) resistance with his first spoken dialogue. This cannot help but evoke Spivak (1988); here, the subaltern (in all senses) is not only actively resisting the authority that controls him but is speaking for himself for the first time. The ‘Organisation Without Initials’ (OWI), as the much-missed site Television Without Pity dubbed it, though global, is primarily shown as being Western/Global North and associated with governmental power and authority over a stigmatised minority.[4] The Haitian’s refusal and subsequent subversion of the OWI’s machinations can thus be read in terms of resistance to neo-colonialist re-enslavement, as Hoermann (2017) terms it. While other characters with similar abilities are referenced in the text – in the 2015 sequel Heroes Reborn, having travelled back in time HRG explicitly asks to work with someone other than the Haitian in order to prevent the Haitian’s death[5] – there does seem to be an implicit engagement with the zombie myth and its associations with the historical Haitian revolution (Glover 2010) in which the majority of Black Haitians fought for and won their independence from colonial France. While Glover (2010) notes that this association can imply an inherent violence in Haitian culture, Heroes displaces the aggression and controlling aspects onto the OWI, who seem to be majority-white and who then act against the minority-superpowered. That the Haitian and HRG ultimately collaborate to help Claire and, eventually, others, can be read as the importance of a power-balanced alliance with sympathetic members of the dominant group.

In Haitian myth, the zombie is an enslaved soul who is as much a victim of oppression and exploitation as those they attack. It has been later appropriations of that myth by Westerners that have turned the zombie from exploited victim to dehumanised monstrosity, paralleling the problematic, arguably imperialist (Cunliffe, 2012, Moreno et al 2012) relationship between the West/Global North and Haiti which continues to the present day. When writing of postcolonial crime fiction, Christian (2001) argues that in those texts, subalterns rarely speak for their cultures and are, in essence, plot devices. As a metonym for Haiti, ‘the Haitian’ (read here as the epitome or archetypal representation of Haitian culture) moves from oppressed, silent enforcer of pseudo-colonial authority to active speaker, resistor and protector of those under similar threat. The metaphor is imperfect – as a secondary character, he supports more than drives the action (though I would argue he is no more a plot device than any other character) – but if the Haitian is first seen as a pseudo-zombie and/or co-opted zombifier, then he grows far beyond that, to reclaim the concept of zombie as both victim of oppression and active resistor to the oppressor.

‘Inite se fós,’ as the traditional Haitian coat of arms states: ‘unity is strength.’[6] Heroes shows this repeatedly across its multiplicity of storylines, in which ostensibly ordinary people, including those with extraordinary abilities, ally with each other to try and protect others from threats of various kinds. But what Heroes also shows us is not only the importance of allies, but the importance of supporting those who have historically been considered to be subaltern when they speak and advocate for themselves so that ‘Libète, Egalite, Fratènite’ (liberty, equality, fraternity),[7] are fundamental to all.

Dr Melissa Beattie is a recovering Classicist who was awarded a PhD in Theatre, Film and TV Studies from Aberystwyth University where she studied Torchwood and national identity through fan/audience research as well as textual analysis. She has published and presented several papers relating to transnational television, audience research and/or national identity. She is suddenly an independent scholar. She has worked at universities in the US, Korea, Pakistan, Armenia, Ethiopia and for a brief time in Cambodia. She can be contacted at tritogeneia@aol.com.

Footnotes

[1] Porter, Lavery and Robson (2007) and Simmons (2011) are the only volumes available, alongside a handful of papers primarily relating to its industrial engagements.

[2] ‘Horn-Rimmed Glasses,’ which the character wears.

[3] I recognise that having his first televised resistance being endangering himself for a white girl can be read as problematic; if read as all powered individuals constituting a threatened minority regardless of other aspects of identity then this can be ameliorated, though not fully eliminated.

[4] This is also a very common reading of Marvel’s X-Men in their many forms (Darowski 2014). Barton (2011) notes that the Heroes comic shows the young René being found by the OWI and brought into their fold; this can be read as a metaphor for the exploitation of natural resources by colonial powers.

[5] …it’s complicated.

[6] The French ‘l’union fait la force’ (‘union makes strength’) is also used along with the kreyol (Haitian Creole).

[7] The French ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ is also sometimes used.

References

Barton K M (2011) Superpowers and Super-Insight: How Back Story and Motivation Emerge through the Heroes Graphic Novels. In Simmons D (ed) (2011). Investigating Heroes: Essays on Truth, Justice and Quality TV. Jefferson NC: McFarland, pp. 66-77.

Chan K (2011) Heroes’ Internationalism: Toward a Cosmopolitical Ethics in Mainstream American Television. In Simmons D (ed). Investigating Heroes: Essays on Truth, Justice and Quality TV. Jefferson NC: McFarland, pp. 144-155.

Christian E (2001) Introducing the post-colonial detective: Putting marginality to work. In Christian E (ed). The Post-Colonial Detective. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 1-16.

Cunliffe P (2012) Still the Spectre at the Feast: Comparisons between Peacekeeping and Imperialism in Peacekeeping Studies Today. International Peacekeeping 19:4, 426-442.

Darowski J J (2014) X-Men and the Mutant Metaphor: Race and Gender in the Comic Books. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Garland C (2015) Hollywood’s Haiti: Allegory, Crisis, and Intervention in The Serpent and The Rainbow and White Zombie. Contemporary French and Francophone Studies, 19(3): 273-283.

Glover K L (2010) New Narratives of Haiti; or, How to Empathize with a Zombie. Small Axe 39: 199-207.

Hoermann R (2017) Figures of Terror: The “Zombie” and the Haitian Revolution. Atlantic Studies 14(2): 152-173.

Moreno M F, et al (2012) Trapped Between Many Worlds: A Post-colonial Perspective on the UN Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH). International Peacekeeping 19:3, 377-392.

Potter A E (2009) Voodoo, Zombies, and Mermaids: U.S. Newspaper Coverage of Haiti. The Geographical Review 99 (2): 208-230.

Porter L Lavery D Robson H (2007). Saving the World: A Guide to Heroes. Toronto: ECW Press.

Simmons D (ed) (2011). Investigating Heroes: Essays on Truth, Justice and Quality TV. Jefferson NC: McFarland.

Spivak GC (1988) Can the subaltern speak? In Nelson C and Grossberg L (eds) Marxism and the

Interpretation of Culture. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, pp.271–313.

Thomas K (2010) Haitian Zombie, Myth, and Modern Identity. Comparative Literature and Culture 12(2): 2-9.