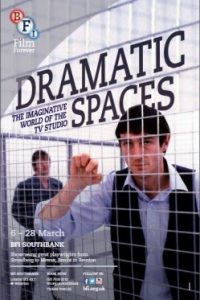

In our ‘post-television’ age when the appearance of television drama and film, both shot on digital camera, is increasingly homogenous, ‘old’ multi-camera studio drama must seem like more of an oddity than ever before. I say that it ‘must’ seem odd because, as someone who watches quite a lot of it (especially plays of the 1970s and early 1980s) the studio drama has become somewhat normalized for me, the shock of its difference lessened through my submergence in that era and mode. However, the experience of co-curating with Dr Billy Smart of Royal Holloway, University of London, a season dedicated to studio plays at BFI Southbank – ‘Dramatic Spaces: The Imaginative World of the Television Studio’ – which ran throughout February 2014, suddenly forced me to become more conscious of contemporary viewers’ perceptions of the form, something that I am not usually required to do, especially as I do not teach my research in this field. I want to reflect here on some of the issues that arose during the process of publicly screening old studio plays, focusing in particular on questions about how we presented our theme of the studio’s possibilities, and the value of such drama now.

In our ‘post-television’ age when the appearance of television drama and film, both shot on digital camera, is increasingly homogenous, ‘old’ multi-camera studio drama must seem like more of an oddity than ever before. I say that it ‘must’ seem odd because, as someone who watches quite a lot of it (especially plays of the 1970s and early 1980s) the studio drama has become somewhat normalized for me, the shock of its difference lessened through my submergence in that era and mode. However, the experience of co-curating with Dr Billy Smart of Royal Holloway, University of London, a season dedicated to studio plays at BFI Southbank – ‘Dramatic Spaces: The Imaginative World of the Television Studio’ – which ran throughout February 2014, suddenly forced me to become more conscious of contemporary viewers’ perceptions of the form, something that I am not usually required to do, especially as I do not teach my research in this field. I want to reflect here on some of the issues that arose during the process of publicly screening old studio plays, focusing in particular on questions about how we presented our theme of the studio’s possibilities, and the value of such drama now.

The dated qualities of analogue video, the harshness of studio lighting, the falseness of setting and the imprecision of live vision-mixing all contribute to what Don Taylor referred to as studio drama’s ‘less complete’ compromise with naturalism which, particularly in single plays, is often also borne out through a more scripted mode of dialogue, and ‘theatrical’ performances. But even though I am aware of how different studio drama is from contemporary drama, I’m used to how it looks and feels – up to a point. Because of the astounding heterogeneity of the single play, in both subject and form, there are always surprises to be found, specific conceits, sets, lines, moments that jump out at you as being unusual even for so eclectic a format, and, as John Ellis (2010) has written about, all old TV seems weird due to ‘the intimate connections between its programmes and the moment of their intended broadcast’, in subject matter, cultural assumptions and production techniques. I wondered how a contemporary audience would find this, and how the experience of members of the audience who had watched the first time would compare to their memories.

A ‘concept-led’ TV Season

As well as the issue of how the peculiarities of old studio form would stand up to contemporary scrutiny, there was a further question mark over our season’s theme. The BFI’s ever-supportive and helpful Television Programmer, Marcus Prince, informed us ours was the first ever ‘concept-led’ television season that the BFI had put on, and therefore something of a test-case. He was not entirely sure that the audience would ‘get’ the notion of celebrating the studio as an organizing principle. This made it particularly hard to predict (a) whether we would attract an audience, (b) who the audience would be and (c) how they would respond to the plays being shown – [1]b) and (c) are admittedly always hard to call). Unlike other recent archive television seasons at the BFI, ours was not tackling a particular genre (such as the Experimental TV season in 2012 and the … Continue reading, but to sophisticated modern eyes well familiar with flexi-narratives, it is quite apparent what is happening and easy to keep up (my husband, viewing the play for the first time in NFT2, looked at me as if I was mad when I asked him if he’d ‘got it’).

Similarly, one suspects that the cartoonish CSO world of the 1978 play The After Dinner Joke which a number of respondents found ‘intrusive and distracting, and the colours so bright that at times they interfered with the outline of the performers’ (BBC WAC ARR: VR/78/83) may be less disorientating to our own post-MTV generation. Some original viewers of Desert of Lies, perhaps switching over from the expensive, location-filmed classic period drama serial Jewel in the Crown on ITV which ended half an hour into the play, complained that the studio desert appeared fake and unconvincing, but even when shown on a large cinema screen, I found it utterly convincing – a masterful piece of set design and direction by Stuart Walker and Piers Haggard, and several BFI audience members commented upon how well-achieved it was (see images above and below).

It surprised me, then, that it is possible for a studio play to be more convincing now than in its original moment, (if anything one would expect it to be less so) perhaps indicating the growing unpopularity of the studio during the 80s as film gradually became the dominant mode, as well as the enthusiasm of a self-selecting BFI audience for a television play, bringing very different expectations and perhaps greater ‘sympathy’ for an old text, than the general TV-viewing public of 1984 could. Another surprise was how well all of our plays stood up to enlargement on the cinema screen. Although the limitations of early CSO technology meant that the captions of Censored Scenes From King Kong were a bit blurry, compositionally they were stunning, and the later CSO play The Journal of Bridget Hitler was a bold tour-de-force when writ large (image below).

A vanished form

It is precisely the diversity and eclecticism of the studio play that makes it so fascinating, and, of course, in a short curated season you can select the best, choice cuts and ignore the huge volume of more mundane offerings. And while I acknowledge that there were plenty of very mediocre and sub-mediocre studio plays, the experience of presenting these plays publicly, briefly introducing them and watching them together with a viewing audience (much larger than that of the individual domestic context of course) really impressed on me the civic value of the studio single play in television history as a heterogeneous form. Although our selection could never be, and was never aiming to be, representative of all studio drama, the variety it encompassed was not atypical. The expectance that there would be original, risk-taking, and frequently ‘rough-around-the edges’ one-off plays regularly transmitted into your home is something very far from today’s situation where slick series and box sets dominate. The value of the single play, like our season, lies not in the particular production but in the cumulative effect of the many different approaches and styles in form, set, dialogue, performance. But as well as that diversity (a quality which extends across filmed plays of the era) there is a further attribute, more specific to studio dramas, that has been lost, which, in our final panel discussion, Piers Haggard (director of Desert of Lies and, famously, Pennies From Heaven) referred to as ‘poeticism’. Returning to my original paraphrasing of Don Taylor, studio drama’s ‘less complete’ compromise with naturalism opened up possibilities of using dramatic conventions in a context that allowed, indeed expected, a level of ‘theatricality’, lyricism, visible crafting, a modernist exposure of form itself, that has all but disappeared now. Watching these plays with an appreciative audience therefore seemed to vindicate the system of television-making that facilitated such an approach. The fact that such a range of texts was on offer, including those that were never going to be popular, is something that it is hard to comprehend in today’s risk-averse context.

Dr Leah Panos is a Post-Doctoral Researcher on the Spaces of Television project based at the University of Reading. Recent case studies for the project include work on the use of the Steadicam in Brookside, the television plays of Howard Schuman, aesthetics in the TV studio musical Rock Follies, and the role of the designer in 1970s dramas using Colour Separation Overlay.

References

| ↑1 | b) and (c) are admittedly always hard to call). Unlike other recent archive television seasons at the BFI, ours was not tackling a particular genre (such as the Experimental TV season in 2012 and the Gothic season in 2013) or theatrical source (such as Greek Tragedy in 2012 or Jacobean Tragedy in 2013), but brought an intentionally diverse range of texts together under the studio umbrella to demonstrate the variety of what could be achieved there. Without an obvious common factor – a genre, person or production company- informing our selections (although, by coincidence, all of our screenings ended up being BBC-made), a lot of thought went into getting the title and strapline of our season right, and it was refined from ‘Spaces of Television’ to ‘Dramatic Spaces: The Unlimited Possibilities of the Television Studio’ (too long-winded) to the final, more inspiring, ‘Imaginative World of the Television Studio’.

It was also decided that we ought to emphasize, in our publicity, the inclusion of famous play-wrights and writers (eg: David Mercer, Howard Brenton, Caryl Churchill, Beryl Bainbridge) and plays (Miss Julie) rather than the involvement of lesser-known directors and designers, (with the exception of Alan Clarke who is more familiar), even though our reasons for selecting the plays primarily concerned how the plays were realised in the studio production process rather than who had written them. It strikes me, though, that our selections were entirely in line with the values that have defined canonical status within television studies, identified by Jonathan Bignell (2005: 19) as ‘programmes that are based on cultural forms that have been accorded greater prestige, such as the adaptation of “classic” literature and theatre, or have assimilated the related value given to authorship in the prestige television play’ and ‘drama that claims, or can be argued to claim, political engagement or to work on the aesthetics of television by adopting new formal conventions’. However, that said, fewer than half of the plays we showed have had scholarly writing on them or are part of the established television canon, a fact that suggests the vast quantity of television that still ‘deserves’ to be rediscovered and our aim of pushing the boundaries of the canon. One difficulty with a season of our type is that the central idea of studio possibilities could only really be borne out across a number of screenings as a single screening could not exemplify all of the many trends that we covered. We selected what we considered to be some of the best examples of various distinct approaches and techniques, and presented them under their own headings: The Unlimited Possibility of the TV Studio (with general introductory lecture) Entrapment & Confrontation in the Studio Studio Trickery Mixing Genres in the Studio The Stripped Down Studio Space Landscape in the Studio This extra layer of curatorial framing allowed the season to develop as almost a course about the variety of studio form, but we knew that it was unlikely that anyone would fully experience it as such, as generally people would make it to only one or two screenings and many would make their selections for different reasons than the particular spatial point of interest we were suggesting: they remember watching a particular play when it first went out; they are studying Brecht; they like Alan Clarke’s work. Our publicity blurb stressed variety and innovation, suggesting that the season demonstrated ‘how the television studio was a site of intense dramatic performance, expressive mise-en-scene and extraordinary imagined worlds’. Reception So, how did the season go? The ticket sales were pretty good, (‘better than expected’ I was told, with all screenings at least half full and some significantly more, but no sell-outs. We were extremely fortunate to have various distinguished production members join us as guests, and their contributions added immeasurably to each screening. These included director Philip Saville, who introduced The Journal of Bridget Hitler, writer Caryl Churchill and producer Margaret Matheson, who gave a short interview before The After-Dinner Joke, and the actors Edward Petherbridge and Clive Swift who joined in the discussion after The Exorcism. Our closing Desert of Lies panel comprised playwright Howard Brenton, director Piers Haggard, and actor Mick Ford, who each offered some illuminating insights on the production and historical perspectives on studio form (a transcript of which will appear soon on the Spaces of Television blog).

Probably the most ‘challenging’ play to a modern sensibility that we showed was the never-transmitted Censored Scenes From King Kong (image above) combining an unusual tone of dialogue, musical numbers and the use of colour separation overlay in some scenes and it was telling that afterwards its writer, Howard Schuman, present at the screening said he felt the reception of the play was ‘polite, if not enthusiastic’, reflecting the tangible sense that viewers were finding it hard to take it all in. One audience-member, (who watches and knows a lot about old television) remarked afterwards that the next play on the double-bill, an epic all-CSO play about the politics of charity by Caryl Churchill, The After-Dinner Joke, was ‘more satisfying, particularly with the benefit of only a single viewing, by virtue of it having a more linear and straightforward narrative’. In other screenings it was clear that the plays were hitting the mark: you could feel a build up of tension in NFT3 during The Saliva Milkshake and Psy-Warriors and hear laughter in all the right places during Desert of Lies. Most importantly, I didn’t hear any laughter in the wrong places – which often belies how badly a text has aged – in any of the screenings. I was also pleasantly surprised to see many more young people in the audiences than I had expected, suggesting that a new generation was exploring this era.

BBC Audience Research Reports show that the formally unconventional Plays for Today: Desert of Lies and The After Dinner Joke were liked only by relatively small sections of their contemporary audiences, and the re-presentation of these texts in our season raised some interesting issues around the context of television schedules, changes in viewing capacities and the retrospective accordance of value. For example the non-linear time structure of Howard Brenton’s Play for Today: Desert of Lies confused many viewers at its original transmission in 1984 (‘they could not follow what was going on and the story was too “mixed-up” and disorientating’ (BBC WAC ARR: TV/84/52 |

|---|

https://cstonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/resizeimage-2.php_-6-140x105.jpeg.webp 140w,

https://cstonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/resizeimage-2.php_-6-140x105.jpeg.webp 140w,  https://cstonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/resizeimage-3.php_-6-140x78.jpeg.webp 140w,

https://cstonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/resizeimage-3.php_-6-140x78.jpeg.webp 140w,