Like many of you (I’m guessing), I have spent much of my HE career teaching the theory elements on practice or production-focused degree programmes. The theory/practice line (and yes, it’s tempting to type ‘division’) can be a challenging one to negotiate, not least in terms of helping students understand how what I do relates to my industry colleagues’ work. I usually pitch it thus: ‘On your other modules, you will be learning how to make stuff. On my modules, you will be looking at stuff that has already been made – and thinking about how and why it was put together the way it was.’

A bit basic, but it gets the point across.

Nevertheless, there is always going to be a certain amount of resistance. Some students come to university not to seek after the eternal truths of visual media, or even to find themselves as human beings, but with the sole aim of getting a job in film or TV – and they honestly don’t see how writing essays (which is what many think theory boils down to) will help them achieve that. I try to head this off by explaining that writing an essay (which is a means of assessing what the student has learned, rather than an end in itself – or should be) can be as much an act of creation as making a short film or a documentary, and – guess what? – demonstrating the ability to set out a clear argument supported by relevant evidence may well turn out to be an advantage when trying for a production job (that’s basically what a pitch is, isn’t it?).

Alas, my almost irresistible positivity does not always work its charms on those students who have already decided theory is ‘the boring bit’ (you have to read stuff? Forget it), and as someone whose research consists to a large extent of comparing working in a studio with multiple cameras to working on a location with just one, I do understand how the ‘messing about with cameras’ element of the degree might be perceived as ‘the fun bit’.

However, by conveying the fact that, yes, I too regard use of the camera as interesting – and worthy of research, which also informs my teaching – I am occasionally able to break down potential resistance; at least, on the students’ part. Convincing colleagues that theory has an important part to play on a practice degree can sometimes be more of a challenge. At my last place, anyone who had read a book about TV instead of actually making it was treated with a mix of suspicion and derision – and if you had written a book about it, you were lucky not to be tarred, feathered and stuck in the stocks.

However, staff resistance to merging theory and practice into a beautifully argued yet practical whole does not always derive from the industry side. At the place before my last place, where I was a mere hourly paid bod, I was once asked to minute a meeting between the theory and practice tutors, designed to seek out new ways of bringing the two closer in teaching terms. In this particular department there was a fifty/fifty theory/practice split, and when a (quite sensible) suggestion was put forward by one of the latter for forging a connection with the former, the theory professor who would have needed to be involved reluctantly sighed: ‘Well, I could do that, I suppose – but it means I would have to change some of what I teach!’

Well, don’t bother, then. God forbid you should have to blow the dust off your slides.

That was nearly a decade ago, and a (theory) colleague who still works there tells me he has in fact been making inroads towards at last bringing the two factions together (think Kaleds versus Thals, Whovians), and thus provide the students with more genuinely holistic learning experience – but it is slow work. Quite often in these situations I think it is a matter of simply waiting for those members of staff whose opposition is most deeply ingrained to either lose the will to fight what they perceive to be the good fight (and academics can be a stubborn bunch), or move on (by which I of course mean either retire, or accept some ghastly, overpaid sinecure at a new place looking to bump up its REF outputs).

Although there were – and are – some progressives among the senior staff, the institution in question had its fair share of professors whose energies were primarily devoted to farming out their teaching to PhD students. Their idea of keeping learning materials up to date essentially consisted of changing the date on their slides five minutes before the lecture. I once saw a particularly eminent and well respected film historian, who had clearly struggled to adapt to the coming of PowerPoint, trying to engage a bunch of truculent first years with the subject of classical Hollywood. She did this by playing a series of corrupted digital files of selected scenes from the Hollywood greats that stuttered and stalled in all the most important places. I later discovered that these files had been made for her some years earlier by a more tech-savvy colleague, but they were now sadly past their best – and she couldn’t be bothered to fix them. Students were therefore treated to Cary Grant in a negligee shouting ‘I just went g– a– -f a sudd–!’ as being in some way representative of Bringing Up Baby’s timeless screwball shenanigans. ‘Well,’ she drawled, another classic moment from the Golden Age effortlessly ruined for the millennials, ‘you get the idea.’

That kind of thing does little to advance the theory cause.

However, even if the tutor in question had given the most inspirational class since Robin Williams had them standing on the tables in Dead Poets Society (which I now realise would require a risk assessment), the professor in question would still have been competing with the more tangible pleasures (for the cohort, at least) of running out of the lecture theatre (remember them?) and doing ground-breaking things with a tripod.

Even when the ‘theory bit’ quite plainly addresses the interests of students who presumably see themselves as the future creatives of film and television, it can end up feeling like sweeping water up a hill. I once invited a very experienced television director, whom I had interviewed as part of my PhD, to help me out with a Q&A on the differences between multi-camera studio and single camera location for my old British TV Fictions module (essentially a television drama history course, with some sitcom thrown in). The gentleman in question had worked on a huge range of shows, and his most recent project had been two episodes of Inside No. 9, which I thought students were actually supposed to like. He had gone to the trouble of bringing along some of the camera scripts, thus presenting the students with a golden opportunity to see authentic contemporary materials and ask questions. Sadly, around 60% of the group just sat there, dead-eyed – because this was a theory class, wasn’t it? You have to attend them, but you’re not allowed to find them interesting, or gain any benefit from them.

I was mortified. My director had driven all the way from London, and was only being given petrol money by way of recompense. I shamefacedly handed him a decent-ish bottle of wine and expressed my profuse thanks – but he never came back.

Ah, well; I’m at a new place now, and I think that this time things might be different. It’s not perfect; I’m the only permanent theory bod on my degree programme, and attendance of my classes is not what it could be. This is largely due, I believe, to the fact that I am once again faced with teaching my ‘boring bits’ entirely online. I know I could connect better with the students if we were in a physical space, and had the chance to build some sort of rapport. At the very least, I could actually see when they were looking bored by my bits, and be able to address the issue on the spot instead of staring into the terrible, silent void that is Collaborate, our VLE teaching tool (other entirely soulless and spirit-killing digital platforms are of course available).

That said, I really enjoyed my pre-Christmas Friday afternoon sessions with the minimal yet loyal number of second years who turned up every week for Screen Performance and Genres (yes, it does sound tailor-made for me, doesn’t it?). Each week we would explore the development of a particular screen genre (the person who wrote the unit had mainly focused on film – which I am very much enjoying teaching again – but I also added some TV classics), then examined the associated performance style or styles. Afterwards, in the seminar (also online), I would show some more clips, and hand over to the students while they carried out their analysis. After all, what exactly does Jack Nicholson do with his voice and body to suggest his character’s mental disintegration in The Shining? These seminars almost felt like the real thing, and the experience was genuinely pleasurable. When the unit ended, I really felt a little wistful. ‘Thanks,’ texted one virtual voice, ‘It’s been really relaxing.’ Now, I’m not sure that university classes should be all that relaxing, but I know what the invisible student meant: we had grown comfortable with our area of study, and with each other. Long before I became an academic, I imagined that seminars would be like the ones you saw on Inspector Morse: silver service tea in a wood-panelled room, with a select handful of interested students. Our room may have been virtual rather than wood-panelled, but some of us had actual tea, and it was a warm and collegial atmosphere in which to teach and (I hope) study.

Since then, I have also been getting some face-to-face contact with my first years – though not on a theory unit.

Yes, I have been co-opted as a practice tutor! Don’t laugh; a change is as good as a rest. My role is to coach various groups of students through the pre-production of a live television news broadcast (the studio work is handled by a professional, but I sit in on those sessions if I’m free). We allocate production roles, pitch ideas based around the brief, write scripts, plan pre-recordings, and watch rushes together. This week we had ersatz run-throughs before students went into the studio for a full dress rehearsal, complete with script supervisor count-downs and silent hand gestures from the floor manager (in the nicest possible sense).

It’s not quite what I imagined I would be doing when I embarked upon my HE teaching career, but it ties in with my theory work, both in the sense that I am exploring the multi-camera studio (albeit for factual, rather than fiction production), and because I am also running a unit on factual TV that is specifically designed to dovetail with the practical work – in exactly the way that my professorial ex-colleague at the place before the last place was reluctant to do all those years ago. So, I’m teaching Caldwell’s concept of videographic televisuality one day, and getting students to think about how they can employ that proliferation of logos, tickers and lower third captions on their own productions the next.

The main benefit to this is that I finally have the chance to meet some of those students who were hitherto merely a list of names in a chat room. When I take my online theory classes now, I can at least visualise some faces (they never want to switch their cameras on, even when I can coax them into using the microphone), and even interact with them on a level beyond the didactic. When COVID first kicked in, I at least knew most of the second and third years I now had to teach online – but for most of the last two years I have struggled to connect with first years (formerly my favourite year group), because – well, we’ve never actually met, have we?

In addition, some of my lovely second years have started saying hello and waving to me when I go for my trademark ham and cheese panino (the singular form of panini), Snickers and cappuccino in the uni café. I have no idea who they are at first, of course, but there’s a chance I’ll be supervising some of their dissertations next year – and if they recognise me (apparently, I’m much taller in real life) it’s because they actually showed up online. I am, therefore, friendly.

There’s still much to be done in terms of breaking down the perceived theory/practice barriers. My new colleagues have all been very welcoming, and the majority of the students are quite proactive; when I tell them to prepare a presentation for the following week, some of them actually do it. However, the first year theory unit I taught before Christmas didn’t quite gel, for some reason, and even in my ‘practice’ classes I can sense that some students are either staying away or not fully participating because they have decided that, as I am just the theory guy, what we’re doing can’t possibly be all that interesting/relevant/useful/fun.

Clearly, it’s going to be a long road – but I think that’s their loss, rather than mine.

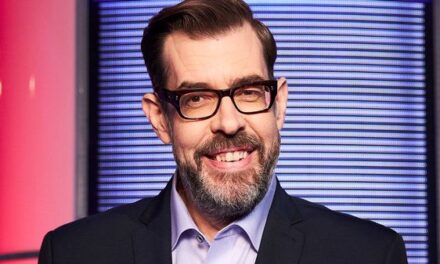

Dr Richard Hewett is Senior Lecturer in Contextual Studies for Film and Television at University of the Arts London. He has previously contributed articles to The Journal of British Cinema and Television, The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Critical Studies in Television, Adaptation, SERIES – International Journal of Serial Narratives and Comedy Studies. His 2017 monograph, The Changing Spaces of Television Acting, was published in paperback form in 2020, and he finally received some royalties from it last year. For further information on academic publications, see here.

Great blog, Richard, and I love your ‘pitch’ to students re theory/practice … and may use it in the future (with full credit, of course!)

Thank you, Jamie! It might still fail to engage those students solely focused on messing about with cameras, but we can only do our best… Good luck!

What a fascinating (and entertaining) read Richard! Always wondered about the dynamics of the two approaches to this field. Beautifully conveyed. Many thanks! 🙂

All the best

Andrew

Thank you, Andrew! I appreciate it. In my case, the risk of being regarded as ‘the boring bit’ is heightened by the fact that I am, at heart, a UK television historian – and many students are now reluctant to engage with anything that isn’t on a streaming subscription service. Sigh.