17th November 2020 marked the fortieth anniversary of the death of 20-year-old University of Leeds student Jacqueline Hill. She was the thirteenth and final woman to be killed in the notorious so-called ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ murders that took place in the north of England over five and a half years from 1975 to 1980. It is a series of events which has cast a murderously misogynist shadow over the cultural history of 1970s Britain.

Jacqueline’s death, and especially the scale of the impact it made, is vividly remembered in the three-part Wall to Wall Media documentary series The Yorkshire Ripper Files: A Very British Crime Story, originally shown over consecutive nights on BBC Four from 26th-28th March 2019.

On 31st July 2020, it won the BAFTA award in the category of Specialist Factual, and as part of their winner’s acceptance speech, the production team behind the series explained that in approaching the subject matter of the Yorkshire Ripper murders, their intention was to explore attitudes to women in the 1970s, and the relationship of such attitudes to the investigation of these killings.

In my interview in October 2019 with filmmaker Liza Williams who directed the series, she likewise stated that “I agreed and wanted to do it was because it looked at the case in a completely different way to anything I’d seen before.”[i] She goes on to specify that the emphasis placed by the documentary on the socio-cultural context of the case, the “wider reasons within society as to why something might happen,” especially in the case of the Yorkshire Ripper murders with regard to gender and class, is what drew her to the subject matter.[ii]

Relatedly, a lot of what is most impactful about the series is the attention it pays and the voice it gives to a number of women that were differently involved in the events of the case, whether directly or tangentially, including as interviewees a number of women journalists, solicitors, academics, and activists and women who survived the attacks.

Williams explained to me that the creative decision taken to privilege the recollections and experiences of women as much as the production team did, and with a view to achieving a genuine “balance” of viewpoints, was a conscious one.[iii] And that this stemmed, in part, from egregious imbalances in the gendered power dynamics that informed the rationale for investigative decisions that were taken at the time of the case, but that have also informed how the case has been narrativized and remembered in mediated form (especially in true crime documentaries) over the decades since.

As Williams expounds on the one hand: “it was a male led investigation. And.. arguably that was part of the problem. They didn’t understand their own biases. So in order to shed light on that we needed to speak to women who would who would see through that and who would be able to reflect on that.”[iv] And on the other: “a lot of documentaries on this subject and on similar subjects focus on the male killer, basically. It’s often [on] his psychological reasons for doing something. They don’t focus on the victims.”[v]

This focus in the series on the experiences and viewpoints of the victims of male violence against women, and on the fact of male violence against women as a social problem both then and now, is just one of the reasons why The Yorkshire Ripper Files is best understood as a revisionist feminist remediation and re-narrativisation of this darkly iconic chapter in 1970s British cultural history. And it is part of a wave of recent media and cultural texts to undertake this kind of reconsideration of the matter. This also includes Carol Ann Lee’s true crime book Somebody’s Mother, Somebody’s Daughter,[vi] which deliberately intervenes in the cultural tendency to mythologise the male serial killer and his inner world by reappropriating the title of Gordon Burn’s 1984 publication about the case Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son,[vii] re-focussing our attention on the victims and away from the perpetrator. And David Byrne and Olivia Hirst’s play The Incident Room, which played at the 2019 Edinburgh festival, and narrates the events of the case as they unfold from the point of view of police detective Megan Winterburn, whose affinity and empathy with the victims is privileged throughout, as is her experience of gendered discrimination in the workplace as she endures male juniors being promoted above her over the course of the investigation. Something all of these cultural texts have in common is their determination to look at the events of the case from the points of view of women.

2019 thus saw a spate of feminist revisionist re-mediations of the Yorkshire Ripper case in UK media and culture, as this cluster of texts focussing on it, of which The Yorkshire Ripper Files is arguably the centrepiece, has emerged in tandem with an explosion in recent years of interest in the true crime genre, alongside renewed attempts being paid by fourth wave feminists to the ongoing need to challenge and combat rape culture. Further, it has emerged at an intersection of these things in the form of the phenomenon of what Tanya Horeck terms and conceptualises as “feminist true crime.”[viii]

In this way and others then, The Yorkshire Ripper Files also prefigures and sits well alongside contemporaneous cognate texts that take a comparable approach to dealing with similar subject matter. So far, such noteworthy points of comparison include HBO’s I’ll Be Gone in the Dark (2020), based upon Michelle McNamara’s immensely moving true crime book of the same name detailing her “obsessive search” for the serial rapist and murderer known as the ‘Golden State Killer,’[ix] and Prime Video’s Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer (2020), which re-narrativizes the investigation of the Bundy’s crimes by both relating the salient events and issues from the points of view of women, and also by contextualising the murders in relation to the social and cultural re-evaluation of gender roles that was heralded by second wave feminism. All three series thus deal with subject matter relating to the serial sexual murders of women by men in proximate timeframes across the 1970s and 1980s, and all three are fundamentally concerned both to give voice to heretofore silenced women, and also with the relationship of their subject matter to its social, cultural and political context, and especially as those contexts relate to feminism and feminist concerns.

There are a number of things that emerge as feminist themes and concerns in The Yorkshire Ripper Files specifically though. These include the role played by the ‘Ripper’ killings in galvanising some aspects of the UK feminist movement, especially a wave of activism that ensued in the weeks following the death (forty years ago this week) of Jacqueline Hill. Also, some of the ways in which quotidian misogynies attendant to cultures of masculinity in Britain in the 1970s led to key evidence and eye witness testimonies in the case being ignored by the investigating authorities. And the extent to which this arguably prolonged and even “enabled” (a word specifically used by Williams on the voice-over) the murders, and for the perpetrator to go un-apprehended for half a decade.

A textual flourish employed by Williams and the production team that is worthy of note here, is the use made on the soundtrack of popular music, current to the depicted period, that seems to comment on some of the misogynist absurdities and masculine hubris that were attendant to the logics that underpinned the investigation of the case, and that thus serve the purpose, at a textual level, of feminist critique.

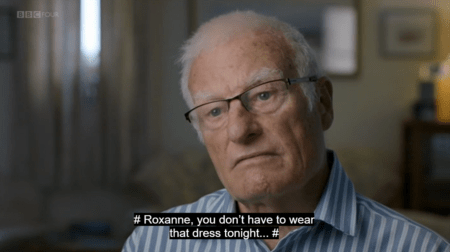

For example, there is something darkly comic about the appearance on the soundtrack of ‘Roxanne’ (a 1978 pop record by The Police, famously sung from the viewpoint of a man infatuated with a sex worker), which immediately follows interview footage of former West Yorkshire Police Chief Superintendent John Domaille’s matter-of-factly misogynist excoriation of murder victim Patricia Atkinson, and her relationship to her own sexuality: “she threw herself about a bit in pubs and it was quite obvious what she was up to. She put herself on show as a woman of loose morals who was wanting to pull fellas.” [#“Roooooooxanne. You don’t have to wear that dress tonight.”#] The candour with which Domaille assassinates Atkinson’s character on the grounds that she was in observable possession of sexual agency is noteworthy for its unselfconsciousness.

Fig. 2: Former West Yorkshire Police Chief Superintendent John Domaille comments on the public behaviour of Patricia Atkinson.

Later, Williams and the production team make similar use of Carly Simon’s ‘You’re So Vain’, a 1970s pop record about masculine hubris, to accompany West Yorkshire Police Chief Constable Ronald Gregory’s infamously tone deaf exclamation of ‘Absolutely delighted!’ in response to the arrest (by members of a different local police force) of the individual who transpired to be the perpetrator. This was after Gregory and his officers had spent years actively chasing a false lead after a hoaxer flattered the ego of Assistant Chief Constable George Oldfield (who at that time led the ‘Ripper’ investigation) in addressing him by name in letters and tapes purporting, falsely, to be from the killer. Seven more women were murdered and several more survived attempted murder by the actual killer during this period of time.

Fig. 3: George Oldfield and Ronald Gregory laughing upon the apprehension of the killer by members of another police force.

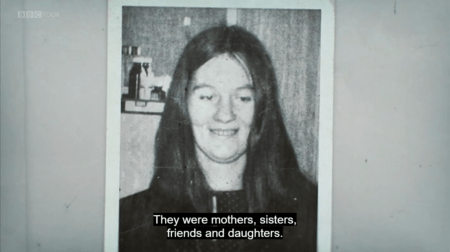

Arguably the most moving moment in The Yorkshire Ripper Files, which also makes a politically charged and high stakes point, comes at the end of the final episode, when we see a succession of photographs of each of the women who died, as Williams’ voice-over explains that the sexist and classist “moral judgement on these women’s lives” played a material part in impeding the apprehension of the person responsible for their deaths. It is an important piece of feminist television that deals with a major flashpoint in twentieth century women’s history in the UK.

Fig. 4: Irene Richardson, as part of the gallery tribute to the murder victims that closes The Yorkshire Ripper Files.

This blog post comes from initial findings of exploratory research towards my new project on media, culture and misogyny in the Yorkshire Ripper years. The first output from this work is available now as “The movie producer, the feminists and the serial killer: UK feminist activism, misogynist 70s film culture and the (non) filming of the Yorkshire Ripper murders” in James Fenwick, Kieran Foster and David Eldridge (eds), Shadow Cinema: The Historical and Production Contexts of Unmade Films (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2020), pp. 235-250. I am currently working on my second book Film, Feminism and Rape Culture in the Yorkshire Ripper Years which is under contract with BFI Publishing (in partnership with Bloomsbury) and due to be published in 2023.

All of my research on this topic is dedicated to the memories of Wilma McCann, Emily Jackson, Irene Richardson, Patricia Atkinson, Jayne MacDonald, Jean Jordan, Yvonne Pearson, Helen Rytka, Vera Millward, Josephine Whitaker, Barbara Leach, Marguerite Walls, and Jacqueline Hill, and to all victims and survivors of violence against women. #EndViolenceAgainstWomen

Hannah Hamad is Senior Lecturer in Media and Communication at Cardiff University, School of Journalism, Media and Culture. She is the author of Postfeminism and Paternity in Contemporary US Film: Framing Fatherhood (New York and London: Routledge, 2014), and is currently working on her second book Film, Feminism and Rape Culture in the Yorkshire Ripper Years (London: BFI Publishing/Bloomsbury, forthcoming 2023).

Notes

[i] Liza Williams, interview with the author [telephone], 15th October 2019.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Carol Ann Lee, Somebody’s Mother, Somebody’s Daughter: True Stories from Victims and Survivors of the Yorkshire Ripper (Michael O’Mara Books, 2019).

[vii] Gordon Burn, Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son: The Story of the Yorkshire Ripper (London: Faber & Faber, 2019 [1984]).

[viii] Tanya Horeck, Justice on Demand: True Crime in the Digital Streaming Era (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2019).

[ix] Michelle McNamara, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer (New York: Harper Collins, 2018).