When creator Adam Price created the political drama series Borgen for Danish television, premiering in 2010, no one thought that international audiences would take an interest in the political life and debates of a small Scandinavian country. As we now know, this turned out not to be the case. BBC4 audiences were in fact curious to follow the political career and personal dramas around Sidse Babett Knudsen’s politician Birgitte Nyborg who becomes the first female prime minister in Denmark at the end of the first season (before this happened in real life with Helle Thorning-Schmidt becoming prime minister in 2011). Other international niche audiences also started watching, and journalists began writing about the Danish ‘hit factory’ with shows such as The Killing, Borgen and The Bridge (Gilbert 2012), with Borgen as a special form of ‘soft power’ that also put Denmark on the map outside of the small screen (Vatsikopoulos 2013).

Fig. 1: Birgitte Nyborg (Sidse Babett Knudsen) and her family as fans know her from election night at the end of the first season of Borgen from 2010. Press still from DR.

Film and television scholars also took an interest, writing about the creative collaborations and public service production framework with ideas about ‘double storytelling’ guiding series such as Borgen (Redvall 2013) and how such series speak both for and to the nation (Hochscherf and Philipsen 2013) or explored ‘why the world fell for Borgen’ (McCabe 2020). In other disciplines, scholars wrote about how journalists worked as tastemakers when Borgen traveled, the democratic quality of political depictions in television fiction (Nitsch et al. 2019), the agenda-setting impact of the series (Boukes, Aalbers and Andersen 2020) or about narratives as equipment for living focusing on the role of spin doctors and spinning around Birgitte Nyborg (Soetart and Rutten 2014).

A successful run – and a surprising revival

From a Danish perspective, it was remarkable to see the world watch the three seasons and dissect and digest everything from a foreign perspective. After the third season aired on Danish screens in 2013, Borgen’s producer Camilla Hammerich published a detailed book about the making of the series (published in English by Arrow Film in 2015). The book felt like a definite goodbye to Birgitte Nyborg and co after an amazing BAFTA and Peabody win and being sold to more than 150 countries. Borgen showrunner Adam Price went on to make a new DR series, Herrens veje/Ride Upon the Storm for DR, while his main screenwriting collaborators went on to create and head big series of their own, such as Bedrag/Follow the Money (Jeppe Gjervig Gram), Ulven kommer/Cry Wolf (Maja Jul Larsen) and Efterforskningen/The Investigation (Tobias Lindholm).

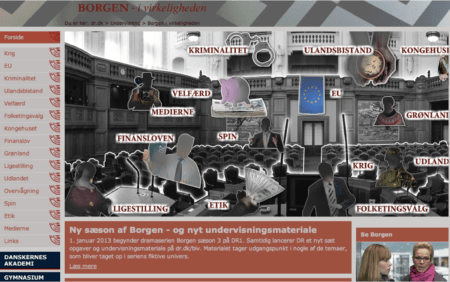

Fig. 2: The first three seasons of Borgen were accompanied with a wide range of teaching materials in Denmark, for instance on Greenland. Screenshot from DR.

There were no signs of anyone planning a revival of the series before DR suddenly announced in April 2020 that Borgen would return with a fourth season based on substantial financing from Netflix (Benner and Roliggaard 2020). This was the first collaboration between DR and Netflix, and both DR’s Director General Maria Rørbye Rønn and then Head of Drama Christian Rank gave several interviews assuring that DR would still have full creative control. This was not a co-production, but pre-selling a license to Netflix after an exclusive run on Danish public service television. Danish viewers could rest assured that the core DNA of the series would remain intact, with DR stressing that there wouldn’t have been money for another season without the financing from Netflix. With that said, there is more than just the economic aspect that has changed since we (thought we) said our goodbyes to Borgen in 2013.

A more serialized new season

We promise that there are no spoilers in this blog, even though the first episode has now been shown on DR this Sunday to strong reviews and decent audience figures (more people watched TV 2’s light historical drama Badehotellet/The Seaside Hotel on Monday last week (1.2 million viewers) compared to Borgen’s 785,000 viewers, but the consolidated numbers are not yet in, https://nielsen.com/dk/da/top-ten/). What we can share is what DR has widely announced, namely that Birgitte Nyborg is now Foreign Minister and has to deal with an Arctic crisis in a serialized set-up. While the previous seasons were, to a greater extent, told episodically, focusing on different political cases from episode to episode, season four follows the same main plot for all eight episodes: an oil discovery in Greenland and the conflicts that follow. Here, Nyborg’s new job title coupled with the global nature of the main conflict cater more naturally to wider international audiences, despite the fact that much in the Borgen universe remains the same with many familiar faces from the first season from more than a decade ago.

Fig. 3: There is a colder feeling to the visual identity of the new season of Borgen… Image from dr.dk.

After the Danish premiere, several reviewers highlighted and praised the first episode’s focus on the complex relationship between Denmark and Greenland. According to showrunner Adam Price, the reason for the revival was suddenly finding ‘the right story’ that not only concerns the Danish-Greenlandic relationship and colonial history, but also foreign affairs and a largescale geopolitical scene, where major powers such as Russia, China, and the United States have great (and growing) interests (Nielsen 2022). In this sense, the new season can be seen as part of the rise of geopolitical television series creating high-end drama engaging with world politics through imaginary scenarios (Chow, Waade, and Saunders 2020, 12). As such, Borgen uses the specific – and for the most part unknown – tensions between Greenland and Denmark to create an internationally relevant narrative touching upon themes of climate change, geopolitics, and decolonization.

The complex relationship between Denmark and Greenland

Despite particular interest in the Greenlandic-Danish theme around the new season in the Danish press, the theme of Greenland is not new to the series. Greenland was at the centre of the narrative of season one (more specifically episode four), when proof of illegally allowed secret rendition flights with CIA prisoners on the much-debated Thule Air Base in north-western Greenland causes a scandal for Nyborg’s newly established government. Thus, the episode touches upon geopolitical issues by – with then main producer Camilla Hammerich’s words – turning the episode “into a thriller about Denmark’s big-brother relationship with Greenland and little-brother relationship with the US” (Hammerich 2015, 230).

Fig. 4: Birgitte Nyborg visits Nuuk and the Greenlandic Prime Minister in the first season of Borgen. Screenshot from Borgen, episode four.

The new main focus on Greenland in season four means a whole new portrayal of Greenland and Greenlanders both on- and off-screen. The season one episode had Greenlandic actor Angunnguaq Larsen in the role of the main Greenlandic character – the Prime Minister of Greenland. In the new episode, not least in the new title sequence, a wide range of well-known and new Greenlandic actors are presented (such as the iconic actor and singer Rasmus Lyberth). In addition, the spectacular urban and rural landscapes of Greenland lend a rawer, or noir, aesthetic to Borgen as it was shot in several different Greenlandic locations. In the first season episode, only a few of the exterior shots were made on-location in Greenland’s capital Nuuk. The new season is based on long-term stays in Greenland with greater involvement of Greenlandic personnel behind the screen and more on-location footage.

Shooting in Greenland with money from Netflix

The shooting of high-end television series in Greenland is a new phenomenon. The 2020 Swedish/Icelandic serial Tunn is/Thin Ice (Jóhann Ævar Grímsson and Søren Stærmose) was the first example but, due to the high production costs in Greenland, Thin Ice was primarily shot in Iceland. This tendency of ‘runaway’ productions that substitute other locations for Greenland has a long history and is still present today – for example with the Icelandic-Danish film Against the Ice which premiered this week at the Berlinale. Although several films have used Greenland as location, it is difficult to imagine that Borgen’s production setups in Nuuk and Ilulissat would have been possible without the financial collaboration of Netflix.

Fig. 5: Greenland is also the setting of Thin Ice, where the Arctic Council ministers meet in the town of Tasiilaq. Like Borgen, the plot is centred on an oil discovery. Screenshot from Thin Ice.

In this sense, the new season of Borgen is unique in several ways. With long shooting periods and a 45-person crew (not counting the actors), the production was challenging because of Greenland’s geographical, climatic, and infrastructural conditions, and the production benefited from the assistance of the newly established production service company Polarama Greenland, which was in fact established after the experiences from Thin Ice (Grønlund 2021a). From an industry perspective, Borgen can be seen as a big step in further professionalizing the emerging Greenlandic film and television industry – for example with the establishment of a film industry organization, FILM.GL, a film workshop, and the annual film festival Nuuk International Film Festival (Grønlund 2021b).

Borgen as a tourist brand and ‘Arctic noir’

While Borgen has thus created new opportunities for Greenlandic talent and the local film and television industry, the series is also an opportunity for advertising Greenland as a tourist attraction. Borgen has already been used extensively in marketing material from the national travel agency Visit Greenland, for instance in a big article, “When Borgen Goes to Greenland”, which focuses on the serial and its use of Greenlandic locations, accompanied by facts about Greenland as well as introductory videos on the central Greenlandic cast (Por 2022). This kind of attention and deliberate marketing use of a production is new in a Greenlandic context and illustrates the perception of Borgen as a strong international brand. As with other series, such as the Swedish Wallander shot in the town of Ystad (Waade 2020a), the collaboration between big productions and local players can generate an interest in screen tourism, and the new season of Borgen taps into that. While the arctic arena on screen ought to be fascinating to both national and international audiences, it also means a lot for a small production culture such as the Greenlandic in several different ways.

Fig. 6: Borgen is already used as marketing material in a big article on Visit Greenland’s website with an introduction to the series, actor spotlights, and (fun) facts. Screenshot from Visit Greenland.

Overall, the new season of Borgen brings both recognisability and change and indicates a current interest in telling stories from and shooting in the Arctic or North Atlantic region. The Faroese-Danish series Trom premiered in Denmark on the same day as Borgen. As the first series set in the Faroe Islands, Trom brings the luscious landscapes of the archipelago into the Nordic noir universe that constantly seems to be looking north – as far as it can get – to create new narratives set in spectacular landscapes, with the term Arctic noir now being a marketing term and also generating academic interest (Hiltunen 2020; Waade 2020b). And from a public service television perspective telling exciting fictional stories from and about Greenland is an excellent ‘double storytelling’ opportunity to also teach Danes as well as international audiences about Greenland and some of the many tensions between not only Denmark and Greenland, but also between the many international players with an interest in the Arctic region. It will be interesting to follow how this unfolds on Danish screens in the weeks to come.

International audiences will, however, have to wait for the Netflix premiere after the DR run.

Anders Grønlund is PhD Fellow at the University of Copenhagen in the Department of Communication. His PhD project (2020-2023) is a study of film and television production in and about Greenland that includes a case study of Borgen. He has published on topics of Greenlandic film, production and location analysis, film history, and Danish Greenland literature.

Eva Novrup Redvall is Associate Professor at the University of Copenhagen where she is head of the Section for Film Studies and Creative Media Industries and principal investigator of the Reaching Young Audiences research project (2019-2024). She has published widely on Danish TV series and Borgen in books and journals since the monograph Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark from 2013.

References

Benner, Torben and Simon Løber Roliggaard. 2020. ’”Det her er en ekstra mulighed.”: Netflix betaler for ny sæson af storsuccesen ’Borgen’’. Politiken, 29 April 2020. https://politiken.dk/kultur/medier/art7765857/Netflix-betaler-for-ny-sæson-af-storsuccesen-Borgen

Boukes, Mark, Lotte Aalbers and Kim Andersen. 2020. ‘Political fact or political fiction? The agenda-setting impact of the political fiction series Borgen on the public and news media’. Communications: 1-23.

Chow, Pei-Sze, Anne Marit Waade, and Robert A. Saunders. 2020. ‘Geopolitical Television Drama Within and Beyond the Nordic Region’. NORDICOM Review 41: 11–27.

Grønlund, Anders. 2021a.’ Man laver film med den ene hånd, og så laver man branchen med den anden: Interview med Emile Hertling Péronard’. Kosmorama 280. https://kosmorama.org/280/emile-peronard.

Grønlund, Anders. 2021b. ’Fra film om Grønland til grønlandsk film’. Kosmorama 280. https://kosmorama.org/280/groenlandsk-film.

Hammerich, Camilla. 2015. The Borgen Experience: Creating TV Drama the Danish Way. London: Arrow Films.

Hiltunen, Kaisa. 2020. ‘Law of the Land: Shades of Nordic Noir in an Arctic Western’. In Linda Badley, Andrew Nestingen, and Jaakko Seppälä (ed.): Nordic Noir, Adaptation, Appropriation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan: 71–87.

Hochscherf, Tobias and Heidi Philipsen. 2017. Beyond the Bridge: Contemporary Danish Television Drama. Bloomsbury.

McCabe, Janet. 2020. ‘Why the World Fell for Borgen: Legitimizing (Trans)National Public Service Broadcasting Culture in the Age of Globalization’. In Anne Marit Waade, Eva Novrup Redvall and Pia Majbritt Jensen (ed.): Danish Television Drama: Global Lessons from a Small Nation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan: 43-62.

Nielsen, Marie Ravn. 2022. ’Nu er han tilbage med “Borgen” – og du skal ikke regne med, at alt er, som det plejer’. DR. 13 February 2022. https://dr.dk/nyheder/kultur/film/nu-er-han-tilbage-med-borgen-og-du-skal-ikke-regne-med-alt-er-som-det-plejer.

Nitsch, Cordula, Olaf Jandura and Peter Bienhaus. 2019. ‘The democratic quality of political depictions in fictional TV entertainment: A comparative content analysis of the political drama Borgen and the journalistic magazine Berlin direkt’. Communications 46 (1): 74-94.

Por, Tanny. 2022. ‘When Borgen Goes to Greenland: Here’s What Happens When Danish Political Drama Series Borgen Meets Greenland’. Visit Greenland. 2022. https://visitgreenland.com/when-borgen-goes-to-greenland/.

Redvall, Eva Novrup. 2013. Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark: From The Kingdom to The Killing. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Soetart, Ronald and Kris Rutten. ‘Rhetoric and narratives as equipment for living: spinning in Borgen’. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 27 (5): 710-721.

Sparre, Kirsten and Unni From. 2017. ‘Journalists as Tastemakers. An analysis of the coverage of the TV series Borgen in a British, Swedish and Danish newsbrand’. In Nete Nørgaard Kristensen and Kristina Riegert (ed.): Cultural Journalism in the Nordic Countries. Gothenburg: Nordicom: 159-178.

Vatsikopoulos, Helen. 2013. Soft power: how TV shows like Borgen put Denmark on the map. The Conversation, 13 November 2013. https://theconversation.com/soft-power-how-tv-shows-like-borgen-put-denmark-on-the-map-20064.

Waade, Anne Marit. 2020a. ‘“Just Follow the Trail of Blood”: Nordic Noir Tourism and Screened Landscapes’. In Anne Marit Waade, Eva Novrup Redvall, and Pia Majbritt Jensen (ed.): Danish Television Drama: Global Lessons from a Small Nation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan: 231–252.

Waade, Anne Marit. 2020b. ‘Arctic Noir on Screen: Midnight Sun (2016–) as a Mix of Geopolitical Criticism and Spectacular, Mythical Landscapes’. In Linda Badley, Andrew Nestingen, and Jaakko Seppälä (ed.): Nordic Noir, Adaptation, Appropriation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan: 37–53.