The holiday season is a particularly good time to enjoy television. All the broadcasters are pulling out the big guns, scheduling the most popular programmes, investing money in some big dramas, and in general trying to please the public through obviously popular fair that is also often very expensive to produce. And I do like my popular fair that has high production values. You might already fondly remember the last episode of Last Tango in Halifax (BBC One, since 2012), or look forward to the next season of Strictly (BBC One since 2004) or I’m a Celebrity (ITV1 since 2002) or whatever equivalents there are on your telly. You might not be able to imagine Christmas without a big family blockbuster (and, yes, they are absolutely crucial too). As far as television is concerned, then, this is when the broadcasters seem to define their brand with the top-range of popular productions, and as a result also define the national television culture.

There is something else involved for me, though, which is also part of this television culture. I also enjoy this time because it signals the return of truly traditional TV viewing: the family snuggled up in front of the telly, watching something together while permanently providing a running commentary to the programme. In the case of our family, this is often ironic, a nice little distancing device in order to keep the emotional resonances of television at bay. One reason for this ironic distancing lies in our nationality: Germans still struggle to enjoy television without feeling in some way guilty, and in such an environment it is hard to take television seriously.[1] To be honest, this is not helped by the quality of the bulk of German productions. While this has taught me to avoid these dramas at other times of the year, at Christmas, there is a true pleasure in indulging in the ‘Schrott’ (scrap metal) that German television often provides while happily critiquing its construction.

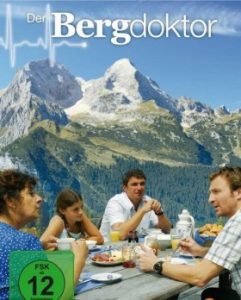

Christmas is then usually the period when I get to watch telly that I would not normally see. I do like my popular television, but really, I am a snob. I like my popular, middle-class TV which, through obvious references, addresses me as an educated member of society. But at Christmas, I ignore my own snobbishness and indulge in the open emotionality and repetitive storylines, as my mother likes to highlight, that are presented to me in German primetime melodrama. Secretly, my parents love these, despite their ability to predict plot developments to a tee through a quick look at the clock. And so, this Christmas, for three weeks, I spent my evenings watching Der Bergdoktor (The Mountain Doctor, ZDF, ORF since 2008), Traumschiff (literally, ‘Dreamboat’, the adaptation of Love Boat and yes, it’s been running on ZDF since 1981) and some one-off dramas on the ARD. And while I was watching, I couldn’t help noticing that the same story was repeated again and again. And it wasn’t about love, and it wasn’t about broken romantic relationships. It was always about missing parents. This, in my eyes, is evidence of a ‘structure of anxiety’ similar to the one that Brunsdon identified in relation to British crime drama of the early 1990s. In British crime drama, this was about ‘who can police? Who is responsible?’ (p.242). In German prime time melodramas at the moment, this ‘structure of anxiety’ relates to the topic that clearly worries Germans more than the economy (largely because they don’t have to worry so much about it as others do): the ‘missing family’.

Much of this anxiety around the family is based on the real problem of dwindling numbers of children being born in Germany. While the UK and other countries are going through a baby boom, leading to a healthy relationship of younger generations to pensioners, particularly in future years, in Germany, there are currently only 8.4 births to every 1,000 inhabitant. In Ireland there are 15.7 to 1,000 and in the UK there are 12.8 as Eurostat reports. One particular concern – and this isn’t uncommon in other countries – is the decline in the number of children being born to (largely white) middle-class families, indicating the usual power imbalances, structured by classist and racist attitudes, as even articles in the rather left-leaning Suedeutsche Zeitung indicate. As usual, there are different reasons put forward why that is the case, with feminism featuring particularly prominently in the criticism of right-wing commentators. Thanks to having a female chancellor who grew up in the former GDR where women did achieve a bit more equality than in the West, and thanks to the driven, internationally educated former minister for family (now the new defence secretary), Ursula von der Leyen, another reason was identified in the lacking availability of childcare for children under the age of 3.

As von der Leyen in an interview with the feminist magazine Emma indicated, this went along with a lack of acceptance for women to return to work when they had small children. For middle-class women, who since the 1970s had been told they could achieve anything if they just worked hard for it (even if they clearly didn’t, as the lacking number of women in CEO positions indicates), this meant choosing between a career and having a family. Many, particularly those women who had seen their own mothers demoralised, if not depressed, by the boredom of staying at home, decided on a career. Von der Leyen’s answer, and she was clearly supported by Angela Merkel in this, was to change the support structure for young families, allowing women to return to work, and hoping that the increase in women returning to work would go along with a gradual change in attitudes.

However, changing attitudes usually takes a long time. While women are increasingly returning to work, they usually do so on a part-time basis, and as several of my German friends (and my sisters) indicate, they now feel under pressure to do more: be mothers, full-time housewives, and part-time paid workers. In that respect, changing childcare provision was clearly not enough, and even changing attitudes towards women in work wasn’t enough. What was also needed, and in my eyes this hasn’t yet happened, as is clearly visible in the German melodramas, is a re-evaluation of masculinities.

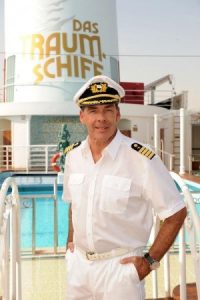

One piece of evidence for the continuation of the same masculinities lies in who populates these (and other) dramas and in what capacity. In Das Traumschiff the pilot is played by Sascha Hehn, whom some international viewers might remember from Die Schwarzwaldklinik (Black Forest Clinic, ZDF, 1985-1989). There he played an aspiring surgeon trying to trump his father with whom he had a competitive, but relatively warm relationship. In the 1980s, Hehn was typical of the male pin-ups of the time, and although perhaps less trendy and cool than Til Schweiger later (Lara Croft, Jan de Bont, 2003, Inglourious Basterds, Quentin Tarantino, 2009), shared quite a few character traits with the latter star’s image. This included a sense of independence which attracted copious numbers of female admirers with none of whom he was able to form a lasting relationship. In the new series of Traumschiff, Hehn still plays the independently-minded man surrounded by lots of admirers, even if he no longer seems to act on his sexual urges. The Bergdoktor (Hans Sigl) too takes on a similar role, although he seems somewhat more settled as a result of being in a long-term relationship. In terms of positively-marked models of masculinity, then, little seems to have changed. And yet, something profound has changed. And that is the role of these masculinities in relation to the family.

In the 1980s and 1990s, as already indicated, these characters were often pitted against benign father figures who they on the one hand troubled, and on the other hand learnt from. They thus presented a chance of working through the patriarchal structures of German society, even if they didn’t quite manage to undermine these. Now, these heroes are central in helping to bring families back together or forming new ones. In other words, these independently-minded, competitive, white, heterosexual, middle-class men are shown to be the leaders that can heal the rift that has opened in German society as a result of the ‘missing families’.

Take Der Bergdoktor. To be fair, I only watched two of this season’s 7 episodes. But in both, the missing parent was central to the solution of the story. In the first one (‘Alte Heimat, Neue Heimat’) the mountain doctor saved the life of a young girl who had been born in the region of Austria where the series is set, but who later lived with her dad in Berlin while her significantly older brother – who like earlier young men was struggling to fully accept the authority of his father – looked after the farm that his mother had left to the family. The episode was solved when it transpired that the girl suffered from the same rare type of diabetes as her mother who had died in childbirth as a result of complications connected to the disease. While the mother’s absence (and her replacement with another mother figure) was an underlying theme throughout the episode, the story emphasised the need for an acknowledgement of her absence, the open discussion of the fact that she was dead, to solve the medical mystery. Within this narrative, the Bergdoktor not only conducted all the medical tests, but also kept trying to bring the family back together, pleading for mutual understanding, offering solutions to the problem of the child’s unhappiness which seemed to exacerbate the symptoms, and finally asking the right question in order to solve the mystery.

In the second episode (‘Zwei Väter’), the Bergdoktor looked after a young, happily married man who was dying from a rare genetic disorder. He could only be saved by a child he had fathered with the wife of his best friend. Here, the story of the ‘missing parent’ is somewhat more complex than that of the first. In this case, what needed to be openly acknowledged was not that the parent was dead or absent in some other form, but that the ‘real’ parent was symbolically absent because he wasn’t known to be the father of the child and indeed not confirmed until a blood test was conducted. Again, it needed the pleading of the Bergdoktor and his questions to save the young man.

Similar stories I found in all – yes all – the series and one-off dramas that I watched: the episode of Das Traumschiff (‘Perth’) told the story of a young boy visiting his dad on the boat and asking him to come back on land where he would settle with his new girlfriend; Die Dienstagsfrauen (The Tuesday Women, ARD, 2014) was actually not at all about the relationship between women, but primarily about one woman looking for her father who had been absent all her life, and Nichts für Feiglinge (Nothing for Cowards, ARD, 2014) was about a young man moving in with his dementia-suffering grandmother with whom he had a difficult relationship as a result of her raising him after the death of his parents. Some of these dramas – the latter in particular – were touching and did raise other questions. But even the best one couldn’t help returning us to the problem of the missing parent. Nichts für Feiglinge clearly had ambitions to seriousness and dealt amongst others with the loss of identity, the problem of dementia in society, and our mortality as well as the pain of losing a parent or a child. It was also the only one that didn’t rely on the individually-minded but benign father figure to unite the families again. In the other dramas, these benign men didn’t necessarily have children themselves (Sascha Hehn’s pilot seemed childless, though the relationship with his top stewardess actually suggested that he took on the father role for the whole of the crew and the guests of the ship). Their role, however, was clearly patriarchal. They were the central authority figures who knew best and who not only had the power but also the ability to heal the rift that the missing parent clearly had created. In a country, famously governed by a ‘Mutti’ (mummy), this requires comment.

To me, it suggests that despite the inroads that feminism has clearly made in Germany thanks to women such as Merkel and von der Leyen, but also to Germany’s leading feminist figure, Alice Schwarzer, the editor of Emma, German mainstream culture remains wedded to the partriarchal ideal. As is suggested in these dramas, problems are there for white, middle-class men to solve. And, these dramas hammer home, this includes the problem that has caused so much anxiety in the last few years: the problem of the lacking German families.

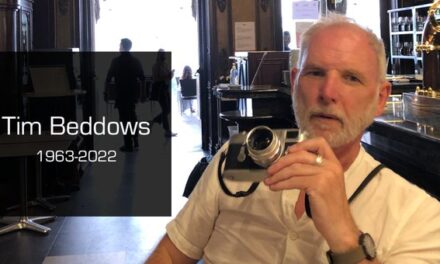

Elke Weissmann is Reader in Film and Television at Edge Hill University. Her books include Transnational Television Drama (Palgrave) and the edited collection Renewing Feminisms (I.B.Tauris) with Helen Thornham. She is vice-chair of the ECREA TV Studies Section and sits on the board of editors for Critical Studies in Television. She migrated to the UK in 2002 after realising that German television was as bad as she remembered.

[1] There are a number of reasons that contribute to this, and I have had several conversations with German colleagues on what they might be. We all agreed, however, that Germany’s relationship to television seems marked by its inability to embrace the medium in a positive way.