The idea of television for dogs sounds like it should be part of a Monty Python (BBC, 1969-1974) sketch but it is a genuine subscription-cable television station available transnationally. Offering programming such as ‘Stimulation,’ ‘Relaxation’ and ‘Exposure,’ on its homepage (accessed 12/11/23), Dog TV advertises itself as:

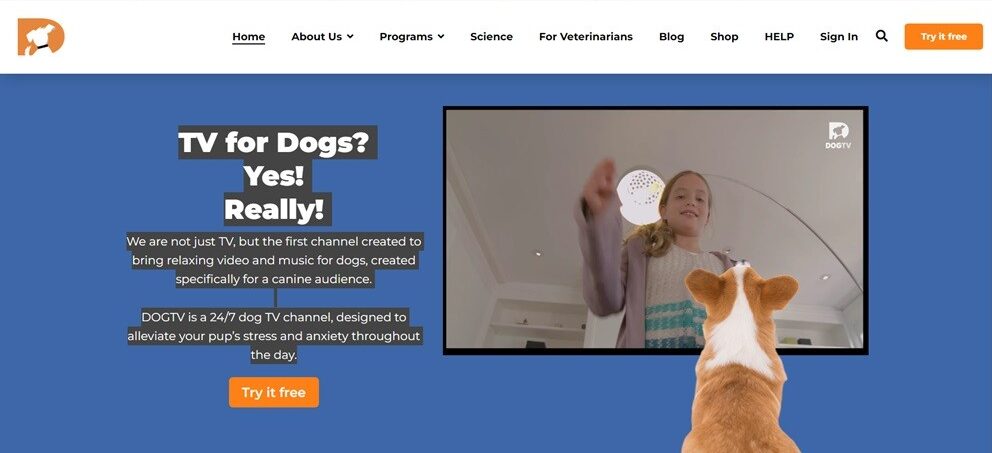

Fig. 1: The webpage/advert for Dog TV

Much like the original HBO advertising which tied itself to distinction and quality (‘It’s Not TV: It’s HBO,’ McCabe and Akass, 2008, Lotz, 2007, inter multa alia), in the screenshot of the homepage above, Dog TV is clearly marketing itself as distinct (in both the Bourdieusian and lay senses) from just leaving the television on any channel when one leaves for work, errands or some other aspect of adult life which requires leaving one’s pet at home. This is somewhat reminiscent of the idea of television as either companion or as background noise, an idea common to the somewhat problematic ‘glance’ theory. If social media, rather than television, is now raising one’s children, perhaps television can be brought in to take care of one’s pets?

Fig. 2: My mother’s dog, Pepper, who enjoys (?) watching TV, especially Monty Python.[1]

In a study on charity advertising, Xu (2021) notes that advertising based upon guilt and/or shame has been repeatedly shown to be effective and that guilt ties in directly with ethical consumption, especially with regard to so-called ‘green’ products. Hibbert et al. (2007) similarly note that the awareness of the use of emotional manipulation by charity advertising does not necessarily negatively impact whether or not someone donates to charity. Chang (2014) connects engaging in prosocial behaviour like donating to charity or engaging in another activity that is perceived to be for the public good through an appeal to one’s own personal benefit (egoistic) rather than to a societal benefit (altruism). This is because the egoistic appeal connects to the viewer’s expectation that their donation/prosocial behaviour will lead to personal happiness. Which is all well and good for charities, but Dog TV is a subscription-based cable channel.

On the homepage itself, Dog TV states that it is specifically ‘designed to alleviate your pup’s stress and anxiety.’ I would argue, then, that the channel is using a very similar advertising mechanism to that of a charity appeal, here playing upon both the emotional closeness of the human-dog relationship as well as the perception that a dog needs more care and/or support (i.e., the ‘cost’ of the relationship) than a cat (González-Ramírez and Landero-Hernández, 2021). The fact that this is one of the few types of cable channels that can appeal to its (potential) viewers in this way also can be used to enhance its perceived distinction: i.e., ‘it’s not TV, it’s emotional/psychological support for your dog (who you leave alone for hours almost every day, you monster).’ The fact that most cable or other television channels cannot realistically engage in the same guilt-based advertising also can be read as allowing for such manipulation to either go unnoticed or at least to not negatively impact consumption (Hibbert et al., 2007).

The concept of a television channel for dogs (or pets in general) seems, on the face of it, ludicrous. While dogs can suffer from separation anxiety and act out as a consequence, simply leaving the television on as their companion can almost be read as anthropomorphising our tendency toward developing parasocial relationships with characters on television onto our dogs. And yet, as Dog TV makes clear, playing upon those discourses of guilt and its alleviation through an ethically-engaged or ethically-encouraged purchase is not simply confined to charity. As its engagement with discourses of distinction and, arguably, quality, in their marketing make clear, Dog TV is trying for more than niche/narrowcasting. Rather, it is presenting itself as a needed service and support for someone the subscriber loves, support which the subscriber cannot provide on their own. In essence, to gain and retain its audience, Dog TV reminds us – and guilts us – into realising that it is a dog’s life, and we are all just living in it.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, Pepper needs to talk to me about a dead parrot…

Dr Melissa Beattie is a recovering Classicist who was awarded a PhD in Theatre, Film and TV Studies from Aberystwyth University where she studied Torchwood and national identity through fan/audience research as well as textual analysis. She has published and presented several papers relating to transnational television, audience research and/or national identity. She is suddenly an independent scholar. She has worked at universities in the US, Korea, Pakistan, Armenia, Ethiopia and for a brief time in Cambodia. She can be contacted at tritogeneia@aol.com.

Footnotes

[1] Pepper recently refused to go to bed until she saw the entire ‘holy hand grenade’ scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975, dir. Gilliam and Jones). Photo courtesy of Barbara Beattie.

[2] In an interview Dog TV’s co-founder, Ron Levi, states that guilt over leaving his cat every day was the inspiration for the channel (Oleck 2017).

References

Bonas S et al (2000). Pets in the network of family relationships: An empirical study. In Podberscek A L et al (eds.), Companion animals and us: Exploring the relationships between people and pets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 209–236.

Chang, C (2014) Guilt regulation: The relative effects of altruistic versus egoistic appeals for charity advertising. Journal of Advertising 43(3): 211–227.

González-Ramírez M T and Landero-Hernández R (2021) Pet–human relationships: Dogs versus cats. Animals 11(2745): 1-8.

Graham L et al (2005). The influence of visual stimulation on the behaviour of dogs housed in a rescue shelter. Animal Welfare 14(2): 143-148. doi:10.1017/S0962728600029146

Hibbert S et al (2007) Guilt appeals: Persuasion knowledge and charitable giving. Psychology & Marketing 24(8): 723–742

Hirskyj-Douglas I (2016) Here’s what dogs see when they watch television. The Conversation, 8 Sept. available from: https://theconversation.com/heres-what-dogs-see-when-they-watch-television-65000 (accessed 12/11/23).

Lotz A D (2007) If it’s not TV, what is it? The case of US subscription television. In Banet-Weiser S et al (eds). Cable Visions: Television Beyond Broadcasting. London: NYU Press, pp. 85-102.

McCabe J and Akass K (2008) It’s not TV: It’s HBO’s original programming: Producing quality TV. In Leverette M et al (eds). It’s Not TV: Watching HBO in the Post-Television Era. London: Routledge, pp. 83-94.

Oleck J (2017) A TV channel for dogs — yes, really — just got some wagging validation. Entrepreneur (4 May). Available from: https://entrepreneur.com/living/a-tv-channel-for-dogs-yes-really-just-got-some/293584

Xu J (2021) The impact of guilt and shame in charity advertising: The role of self-construal. International Journal of Nonprofit Volunteer Sector Marketing 1709: 1-13.

RIP Pepper Beattie.