Back in January 2012, when I was nudging towards the end of my PhD, two old friends and I embarked on a road trip to Wigan to celebrate another chum’s fortieth birthday. We drank and danced and had a merry old time, though I suspect the birthday boy bunged his karaoke man a fiver to make sure I didn’t get a look-in. The public was therefore deprived of my definitive ‘Love is the Drug’.[1]

En route home the following day we decided to stop off at Alsager, the ‘small field in Cheshire’ that played host to the campus where we had all met as undergrads back in 1992. This was of course the year that a substantial number of Higher Education institutions morphed into universities overnight, Crewe and Alsager College of Higher Education (to which we had applied) becoming the umpteenth faculty of Manchester Metropolitan University (from which we later graduated). Since our old campus had closed for business in 2010, we were curious to see what kind of state it was in. At that point the majority of the site was still standing, though I understand the bulldozers have since moved in. Sadly, the Crewe campus is now also closing its doors, and as of this summer MMU Cheshire will be no more.

I have no special affection for the Crewe campus, which I only visited three times in as many years (their discos weren’t a patch on ours), and the Cheshire branding only came into effect after I’d left. However, I mourn its passing. The closure is apparently due to the faculty being ‘neither academically nor financially sustainable’, and when the news broke in 2016 I was happy to append both my name and my two-penny worth to the UCU’s online petition: ‘Higher Education should be about opening doors, not slamming them shut.’

Rousing stuff, and much good it did.

I don’t know what is happening to the Crewe staff, though when I looked at the website for the Department of Contemporary Arts I noted that all the phone numbers had a Manchester prefix. It was nice to see a few familiar faces there. Associate HoD Bev Stevens supervised my final year Honours Project (of which more anon), and I also remember Jane Turner, though she never taught me. I actually graduated alongside Anna Macdonald, who I believe began teaching at Alsager not long afterwards, while Jason Woolley was in the year below mine. We were fellow tenors in the choir, and the band I was in once provided somewhat unsteady support for his group at a Crewe hostelry.

Happy times, long since passed.

I have blogged before about where I (and others, judging from the responses I received) sometimes worry that HE is heading, and my concern that, in our desire to ‘skill’ modern students for industry, we are perhaps encouraging them to focus more on the ‘how’ of achieving passes in assessed modules than the ‘why’ that was still the essence of the university experience when I took my degree. Over those three years I was constantly encouraged to think through the concepts that were being presented, and to produce work that explored and maybe even challenged them, rather than simply demonstrating that I had understood their gist and could apply them on some level. While I was desirous of passing my course and attaining a good grade, there were things I wanted to say and do that did not necessarily repeat established patterns in a bid to tick my tutors’ boxes. I’m sure they wouldn’t have liked that, anyway. Who wants to paint by numbers at that level? The way I saw it, the degree was about the learning experience, and not just the qualification.

These days I often say that lecturers are responsible for teaching, not learning; the latter is the student’s affair. Otherwise, every student would presumably graduate with exactly the same grades, since they all receive the same teaching input (assuming they attend classes and complete their assigned work). The teaching I received at Alsager was often inspired – and at times inspiring – and I made the effort to learn from it.

Creative Arts was a modular degree, combining practice and theory. Each student specialised in two disciplines in their first year (chosen from Visual Arts, Music, Creative Writing, Drama and Dance), but we could then diversify or specialise as we progressed through the course. The core first year module was Integrated Arts, comprising a theory lecture on Tuesday morning and a practice session in the afternoon. It was in the latter that my group’s installation-cum-performance art piece infamously earned us a cabbage instead of an actual grade. You can read about that in more detail here, but the argument was that, as we had not presented them with a proper piece, they were not going to give us a proper mark. I remember our tutor, Neil Fisher, delivering his judgement with a smile. Some of the others in my group grumbled a bit, but I thought it was quite amusing, and in the spirit of the course – and they didn’t actually fail us.

Our tutors were a mix of artists and academics. If I recall correctly, Creative Arts was run by the then Doctor but now Professor Robin Nelson, while a gentleman called Piers Nicholls led Integrated Arts. Robin had a goatee beard, wore leather waistcoats and immediately commanded everyone’s respect. It was in his seminar that I first heard the second syllable of surrealism pronounced ‘rail’; a real eye-opener. He awarded me 67% for my first full-length essay, which examined Kazimir Malevich’s White On White as a seminal work of Abstract Expressionism (or more accurately Suprematism), and I was more than happy with that. This was, of course, back in the days when students didn’t immediately email their tutors upon receipt of a 2.1 to query why they didn’t get a First. For one thing, we didn’t possess email. For another, we trusted our tutors to know what they were doing. My mark indicated I was doing more things right than wrong, which I regarded as a promising start. So, it pleased me; there was plenty of time to improve.[2]

Piers Nicholls, who came up with the ‘field in Cheshire’ line, looked a like a young Patrick Moore. With a wit that can only be described as undergraduate, he was swiftly nicknamed ‘Pierced Nipples’ behind his back. Piers was popular because he was a bit of a performer. I remember him giving a lecture on semiotics in the first term (we did a lot of semiotics back then) in which he had clearly pre-arranged for another tutor, Ondre Nowakowski, to quietly walk up to the podium and present him with a rose, mid-flow. Piers then turned to his audience, all innocence, and asked us what this might signify.

Cue much nervous giggling from the idiot first years.

Piers was not a music tutor, but during our end of year summer project, when we re-interpreted the legend of Prometheus for the locals in our field, he sat down at the piano and jammed with us music students on ‘I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free’. It was a nice moment.

This makes it sound as though we were some kind of lovely tutor-student co-operative, but it wasn’t like that at all. Although tutors might chat with students in the refectory, the Wesley Centre (where I survived for three years on a daily lunch of congealed pizza and chips, and didn’t put on a pound in weight), or (less often) in the union bar or the Lodge pub, there was a clear sense of the power dynamic. Lecturers were there to give us what we needed during contact hours, and then it was up to us to go away and get on with it. If we became stuck, we could request an appointment to meet and discuss the problem in their office. I felt no sense of entitlement or ownership over my teachers, and would have been far too embarrassed to ask them to repeat information they had already provided in class.

How times have changed.

This was, blissfully, long before the advent of Tweeter, Instantgram and the various sociable media that are now so prevalent.[3] While the staff at Alsager were approachable, there was no over-familiarity. Had WhatsApp existed then, staff would not have conducted group chats with us on the basis that this was the only way to convey information (‘Well, students don’t read emails any more, do they?’). And you know what? I’m grateful I didn’t have that kind of relationship with them.[4] As a lecturer, it’s nice to receive feedback praising our approachability (which we do) – but it is not my job to make friends with them. As I see it, I am responsible for pointing them on their way to becoming independent learners and thinkers – I am not obliged to be their pal.

The problem is that befriending a student (or appearing to befriend them, which I suspect is what it more often boils down to) increases their sense that we will be there to help them out at every stage of their career (what else are friends for?) – which of course we can’t be. This makes learners overly dependent on us, decreasing the requirement for them to think for themselves and thus diminishing their ability to do so. This is very bad news indeed – for them and us – and does not provide a particularly solid grounding for their future professional development. What kind of employer wants staff that can’t follow instructions? Who refuse to take responsibility for their actions? Or who email at all hours to check they are on the right lines? It’s entirely natural for students to want guidance, but we seem to have reached a stage where the prevailing attitude is:

‘Show/tell me what to do.

Show/tell me again.

And again.

OK, I guess I’ll try to do it for myself –

No! Don’t leave me on my own. I need you here in case I make a mistake.’

This could range from the expectation that tutors read essay drafts prior to submission (which I refuse point blank to do),[5] to staff literally telling students how to edit their productions, step by step.[6] I didn’t ask Robin Nelson what he wanted me to write about Kazimir Malevich; I wouldn’t have had the nerve. Neither did I ask him which books he expected me to quote, and I certainly didn’t request that he show me where on the library shelves they could be located.[7]

Of course, some tutors, aware of the need to get positive feedback in the NSS, are happy to oblige. But whether they make themselves so available out of genuine altruism or because they see it as the quick and easy path to success, in the long run they are helping neither themselves nor the student. I have tried to model my behaviour as a lecturer on what I experienced myself as a student. At Alsager I was treated like an independent-minded adult; I always felt that my tutors took me seriously. I wasn’t regarded as another sausage in the sausage factory, or as a customer to be served and got out of the shop with minimum fuss. Ours was an inclusive, professional working environment, which showed me that it is possible for tutors to be supportive without leading students by the nose. In addition, we were encouraged to pursue our own creative vision – which meant we sometimes produced work that tutors might not necessarily like. This was, after all, what most of the people we were studying had done. Marcel Duchamp must have known that the Society of Independent Artists weren’t necessarily going to approve of his Fountain (an inverted urinal), but he submitted it for exhibition just the same (though admittedly he did so under the pseudonym R. Mutt, so he could then protest vigorously at its non-inclusion without anyone knowing it was his). Our creative artist heroes were rule-breakers; iconoclasts who didn’t toe the line just so they could get a First. We wanted to be just like them when we grew up – but on our own terms.

I do sometimes wonder who or what my students want to be like when they grow up.

My own artistic statement of intent came in the form of my afore-mentioned Honours Project, which was titled Doctor Who and the Deconstruction of Time. Each Project was a performance or installation piece that we put on in the first term of our final year. It could pretty much be anything we liked, but the main rule was that we were not allowed to appear in our own productions, and had to make use of other students on the degree (including first year volunteers) in order to realise it.

This was too good an opportunity to miss: the culmination of two years’ study – or, in my case, a reaction against it.

Yes, I’d had enough of analysing the text. Why, I presumptuously wondered, couldn’t we just enjoy things for what they were, without always having to pull them apart?

Silly boy.

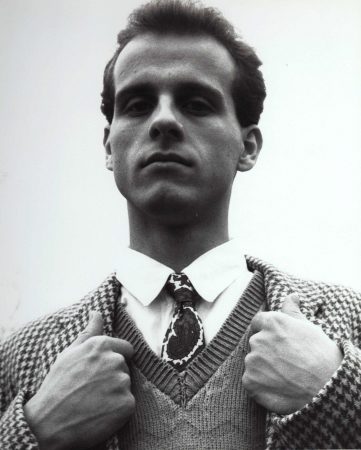

Ah, well. While at university, my early love for Doctor Who – which had been rent asunder tragically during Sylvester McCoy’s first year on the show – was rekindled by my course-mate Luke Simonds, with whom I watched many VHS cassettes of classic episodes from the 60s, 70s and early 80s. When I asked whether he’d be willing to take on the mantle of our favourite Time Lord for my show, he didn’t require a Troughton-like series of increased pay inducements (which was just as well). Plus, he already had the gear, including a licensed McCoy tank top (see below):

What could possibly go wrong?

Doctor Who and the Deconstruction of Time was basically an extended exercise in cocking an impudent snook at the degree and tutors I have spent most of this blog eulogising, in a feeble attempt to critique the course’s raison d’etre. The narrative begins with a shambling figure in an anorak (played by my band-mate, Alan) walking to the rear of the Dance Theatre (which is probably now a row of bungalows) and switching on a television set. A BBC continuity announcer (me, in a pre-record; well, I didn’t actually appear as such, did I?) then announces a special thirty-first anniversary episode of Doctor Who (this was the 2nd of December 1994, so we were over a week late). As the title music plays, the Doctor and his companion (essayed by a different actor in every scene, to highlight the interchangeable nature of the role in the classic series; clever eh?) enter the set, Luke miming the operation of the TARDIS console to his heart’s content. In a brilliant piece of scripting, the companion is only given bland feed lines such as ‘Where are we, Doctor?’ and ‘What is it, Doctor?’ In the following scene we see a Thal, Anadin (my house-mate, Paul), being exterminated by an off-stage Dalek. Paul enjoyed his moment, despite experiencing a slight underwear malfunction. I couldn’t afford a life-size Dalek, so I made one out of cardboard and lit it (briefly) from behind a screen, thus creating a terrifying silhouette. The Doctor and his companion arrive, and the former deduces that they must be on the planet Skaro. There then follows a lot of running around, plus a couple of Forced Entertainment-style ‘running on the spot’ dance routines (courtesy of my first year volunteers), before the Doctor is confronted by Brechtos, the Deconstructor (played by our friend Matt, who I haven’t seen since his wedding back in 2010). Brechtos then explains his plan to use a Semiotic Analyser (in reality a Lenor bottle with the cap glued on the wrong way round, painted black) to deconstruct the Doctor’s text and recreate it in his own evil image. The Doctor seems doomed until the Anorak (remember him? He has been sitting at the back all the way through, watching his telly) intervenes and tussles with Brechtos, while the Doctor tinkers desperately with his enemy’s weapon. When Brechtos overcomes the Anorak and tries to fire the Analyser at the Doctor, it is in fact Brechtos who deconstructs (‘WHAT – IS – HAPPENING – TO – ME???’: a wonderful line reading by Matt). The Doctor explains that he used the Suspension of Disbelief circuit from the TARDIS to reverse the polarity of the Analyser’s neutron flow (obviously), and thus turn Brechtos’s evil weapon against him. The companion arrives and (predictably) asks the Doctor what is going on, and in time-honoured fashion he promises to explain later. They then offer the Anorak a lift in the TARDIS, and he asks to be taken to a Doctor Who convention in Birmingham.

Cue closing title music.

If the above synopsis has whetted your appetite for more, you can watch the whole thing here. I meant to add subtitles, but there simply hasn’t been time. Luke and I are, however, planning to record a commentary in time for the twenty-fifth anniversary later this year. No copyright infringement is intended, though I did rely extensively on Doctor Who sound effects and music scores, plus David Bowie’s ‘Scary Monsters and Super Creeps’. The video begins with me welcoming the audience, and warning them that a strobe would be used as part of the performance. ‘Tutors to the front’ was a clarion call that will now, alas, be heard no more.

Sigh.

The extremely raucous reception we were given at the close is, I think, more indicative of the fact that it marked the end of Honours Project fortnight (a stressful time for everyone involved), and that we were all heading off to our annual Snow Ball dance that evening (hence my dinner jacket and dicky bow), than a reflection of its quality as a piece of serious art.

As mentioned earlier, Bev Stevens was my supervisor for Deconstruction. Given its aim and content, I think we were aware it was not going to earn me a First, but Bev cheerfully offered encouragement and sage advice, gave me enough rope to hang myself, and basically let me get on with it. The viva afterwards was a rum do. I seem to remember Neil Fisher struggling to keep a straight face, but at least he didn’t give me a cabbage this time. To their credit, nobody said ‘You shouldn’t have done it like that; you should have done it like this.’ They were just politely curious as to why I had done it the way I did, nodded, and left it at that.

Degree policy was that, while a mark could not go down as the result of a viva, it could go up if the student gave a particularly good account of themself.

I don’t think my mark went up much. I received a fair-to-middling 2.2 for the Honours Project module, though I still ended up with a 2.1 degree classification overall.

Today a student awarded such a mark might well respond, ‘But I worked really hard on it!’ (as indeed I did), but I didn’t mind. I had done what I wanted to do, and it got what my tutors thought it deserved. Fair enough. The project was essentially a panto, and though it’s not the work I would make today (when I hope I have acquired a somewhat more nuanced appreciation of the value of textual analysis), it still makes me chuckle – and we were proud of it at the time. I was the toast of the Lodge that weekend, believe you me, and was fighting off admirers at the Snow Ball.

Bliss it was to be alive, but to be young was very heaven.

Ah, well. To quote another franchise, it was all a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away.

I am perhaps being hard on modern students, who are subject to pressures that I did not experience as an undergraduate. I paid no tuition fees, and left university with no debts (I had no money, but no debts). I did not grow up within the results-focused SAT culture, though I do remember everyone getting very stressed by the Eleven Plus. I was extremely fortunate, I think, to have enjoyed my education as much as I did. And I still enjoy teaching, most of the time. But what should be an essentially pleasurable experience – for tutors and students alike – has had some of the joy sucked out of it. For me, that is what MMU Cheshire’s closure represents. However, I’m reluctant to end the blogging year on so maudlin a note, and will instead conclude by paying tribute to the many tutors who tried to show me which end was up in those three very happy years at the Alsager campus. I wish them all well, whatever they are up to now, and hope they would be pleased to know that their efforts ultimately inspired some of us to continue with or re-enter Higher Education; I know that several of my cohort have gone on to work in the creative arts.

Have a good summer, everyone.

Dr Richard Hewett lectures in media theory, and has contributed articles to The Journal of British Cinema and Television, The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Critical Studies in Television and Adaptation. His book, The Changing Spaces of Television Acting: From Studio Realism to Location Realism in BBC Television Drama, was published in 2017; a paperback version will be available in 2020.

Footnotes:

[1] This was most unfair, as I had ensured that he had a fair crack of the microphone at my own celebrations two years earlier. Revenge will be served cold at my fiftieth.

[2] And improve I did. I finally got my essay First from Steve Purcell in Integrated Arts 2A, for a piece that discussed whether or not the Marx Brothers can be considered Brechtian performers.

[3] I am on LinkedIn, but only accept contact requests from students after they have graduated.

[4] For one thing, Pierced Nipples would have found out about his nickname almost immediately.

[5] Discuss their ideas on how to address the brief, certainly. Maybe work out a rough essay plan. And then LET THEM GET ON WITH IT.

[6] I used to have a colleague who regularly advised students to ‘add the Benny Hill theme’ to their films, because this ‘would make it funnier’. Ah, the magic of editing. The sad thing is that most of them had no idea who Benny Hill was, so she had to sing it for them.

[7] Sad to say, this has actually happened to me since I became a lecturer.

Your YouTube video comes up “unavailable”. I am longing to see it so please fix the link.

Splendid!

Thanks, Jules! It’s nice to know some of the old crowd are reading.

Amazing article Richard, thank you! I stumbled across it recently, 5 years after you’d posted it, in a strange twist of fate involving a student I mentor showing me her essay sources, one of which jumped out at me: ‘Robin Nelson’!!! He was my course leader when I joined Alsager in ’89 on the Creative Arts degree. I googled and your article presented itself too! Your memories of the lecturers, the ethos, the campus et al are mine also – happy days! I’ve now discovered (and joined) the FB Crewe & Alsager group 🙂

What is the pop of crewe

The Creative Arts tutors may not have been over-familiar but the Humanities tutors bloody were…

A fantastic article which I have come across quite by chance while googling the fate of Crewe and Alsager campus. As one of the first year students involved (I remember clearly emerging from the audience as Cyberman), I have happily been transported back to that Friday evening in December 1994.

Many, many thanks for bringing the memories back (and should the link to the video become available again, I would love to see it :-))