Jenji Kohan’s Orange is the New Black (OITNB) (2013 –) has gained a reputation for unabashedly screening female faces and body-types that centric media often overlooks. From its opening sequence, OITNB spotlights a vast array of female bodies. The title track blasts out to a montage of fragmented yet intimately close-up faces, comprising of skins old and young, thin and fat, black and white, Latina and – as the series dryly puts it – ‘other’. Yet whilst OITNB portrays a refreshingly variegated understanding of femininity, its initial imagined audience appeared to be somewhat uniform – anticipated (as this blog suggests) as occupying a space which aligned with the show’s white, middle-class female protagonist Piper. OITNB creator Jenji Kohan has repeatedly described artisan soap-merchant cum convict Piper as a ‘Trojan horse’, through whom the viewer is smuggled into the ‘strange’ world of Litchfield prison. Only through their affiliation with Piper’s identity, Kohan implies, is this viewer able to desire, access and understand the space and inhabitants of Litchfield. Except not all OITNB viewers are white, middle-class females, and those that are still may struggle to identify with spoiled, selfish and often weak Piper as an “every (wo)man” character. This blog discusses the use of the female grotesque within the show as a discursive visual and audio strategy by which viewers’ relationships with, and responses to, Piper and “the inmates” are often constructed. Through developing the grotesque as a visual and acoustic ‘encroachment’ upon the viewer’s imagined and projected bodily space, Piper is arguably made more palatable as a “host” perspective whilst the inmates are – intermittently – Othered.

The grotesque body is defined by Mary Russo as ‘open, protruding, irregular, secreting, multiple, and changing’ (1994, 8). Regardless of their colour, age or body-type, the female bodies of OITNB inmates frequently match this description. Inmates are bodily aligned with public urination, sweat, arm-pit stubble, communal urethra inspection, vomit, much-discussed defecation, rotting smiles, bestiality, elephantine breathing-machines, snoring, farting, toe-shaving and ear-wax picking. Always, it seems, the inmates’ bodies are exceeding and excreting around Piper, and by association, around ‘us’. In contrast, Piper epitomizes the archetypal “Classical” or bourgeois body to almost parodic effect. Greeting us with the opening lines, ‘I have always loved getting clean’, we “meet” Piper through a chronological series of blissful bathing scenes, abruptly concluded by a dank, nervous prison shower, complete with Maxi-pad shower slippers. Having been solemnly sworn not to return home with a uni-brow, much of blonde, beautiful, manicured, trimmed and tanned Piper’s early trials in prison revolve about her navigation of the grotesque bodies which surround her, and the maintenance of her own discretion from their often probing, multiple and extending selves. In an early scene, Piper’s refusal of a doorless toilet-stall in a communal bathroom is met with the wry advice, ‘give it a week, you’ll be pissing and farting with the rest of us’. This promise never quite rings true; as we traffic along with Piper’s experiences, the inmates’ bodily excesses arguably become intrusive of our ear-shot and vision. Piper’s sleek, isolated body becomes (and remains) a safe-haven from such excesses, allowing for a certain sense of closeness with an otherwise perhaps less-relatable Piper. [1]Although Piper does open her body to a sexual encounter with inmate Alex, this is in an emotionally-based relationship which precedes both characters’ prison experiences and identities; furthermore … Continue reading

Often these grotesqueries are nuanced, building a slow but resonant sense of distaste for the inmate’s bodies. On one of Piper’s first mornings in prison, as she attempts to change her bra, a medley of sounds develop about her. The fast, heavy gasps of one roommate’s breathing-machine are met by the prolonged snot-hocking of another; the inimitable sound of a hair being tweezed rises to the fore as one roommate plucks her nipples. As the roommates begin squabbling, the medley makes for an immersive sensation of the grotesque, and a subtle subversion of characters who perhaps other-times may appeal more than Piper herself. As the bodies about Piper exceed their limitations, and threaten those of the viewer’s “host” character, the viewer is encouraged to hide within the safe confines of Piper’s nice, discreet, bourgeois body. Indeed, although we are likely meant to laugh at Piper – to acknowledge how spoilt and ‘privileged’ she is – as the construction of the prison’s unique bodily grotesque intensifies, a visual and aural alignment with Piper is frequently produced.

In a less understated scene, when Piper is served a used-tampon burger for lunch, POV is used alongside sound. Here, viewers are largely contained within with Piper’s POV, and offered her perspective of both the sandwich, and her fellow inmates’ reactions to it. When Piper first sits down for lunch, her lunch-mates are discussing Nichol’s new teeth, replacements for those she had ‘knocked out’. Inmate Morello admires them saying, ‘You never get the food stuck in them, so you got the nice fresh breath all the time…’. As Nichols leans over to expose her teeth, already there is a sense of intrusion, of inmates’ bodies and their smells being constantly present and invasive of Piper’s body, the space that we temporarily, sympathetically inhabit. As Piper cautiously lifts the top of her burger bap to expose a soiled tampon, and as her distressed gaze switches between her lunchmates to find only unsympathetic laughter and rebuttal, the camera zooms to an tight frame of each face. The inmates’ open mouths expose half-chewed food as they begin spewing forward directives in a ceaseless chain, again bordering on the corporeally intrusive. Advice on orientation and Piper’s relationship with the kitchen staff mingles with tips to check the elastic on her second-hand prison-issue underpants. As the camera pans from face to face, each contorted with chewing and laughing and talking all at once, Nichols reminds Piper of the ‘nice shower’ she had that morning, wherein Piper accidentally saw Nichols giving Morello oral-sex. The scene’s background music heightens and Piper’s claustrophobia and disgust at these women’s bodies becomes palpable. As Piper leaves there is an element of relief for the viewer too, when the camera zooms out and allows some release from the inmates’ bodies.

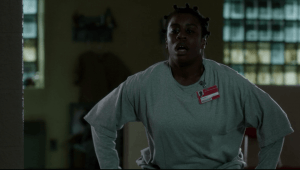

Perhaps even more excessive than the tampon-burger – which is at least a second-hand, anonymous excrement – is Piper’s unrequited lover Suzanne’s “vengeance pee”. Again, this scene begins with an acoustic reminder of the constant presence of other women’s endlessly noisy, producing bodies: in this case Piper’s roommate’s guttural snores. As the sleeping Piper’s eyes open, the camera pans – apparently in sympathy with Piper’s gaze – to show Suzanne, who stands staring at Piper’s bed. Whilst we watch Suzanne’s face, the distinct, unbelievable, sound of urine splashing against a hard floor begins. The camera pans down to confirm this, and we witness alongside Piper a stream of urine, pooling at the bedside floor. The camera shifts to Piper’s roommate, whose opening eyes and sniffing nostrils convey the presence of a strong stench. A full-bodied sensual experience is rendered as the audience is presented with the sight, sound and implied scent of Suzanne’s urine. As Suzanne nods and smiles, the triumphant lines of Boss’ “I Don’t give a Fuck” begin to play and the episode cuts to the end credits. The viewer is left to “absorb” with Piper not only the act of urination, but of the perceived pride which accompanies it. Here, then, again, the the textual construction of the grotesque encourages audience alignment with Piper.

These early grotesqueries suggest an effective textual strategy at play, allowing the sporadic unification of perhaps otherwise disparate audiences within the adopted identity Piper. Yet, by Season 3, Litchfield is no longer so foreign to Piper or the viewer. The show’s motivation evolves,from telling Piper’s journey, to telling the stories of female prisoners more generally. OITNB’s fourth season is imminent, and though Piper is still no closer to ‘farting and pissing’ with the rest of them, “the rest of them” are farting and pissing differently. Now, as Litchfield’s “Other” inmates narratively centralise, their female grotesquery is more-often presented as an unwilling state, a position forced upon them by the prison. The prison toilets break, forcing the women to use a communal bucket. Bed bugs infest the inmates’ mattresses, seemingly transmitted from the prison guard quarters; the inmates alone are visually marked as “infested”, having to burn their clothes, and wear refuse-sacks. During an inter-prison transfer flight, one prisoner wisely advises Piper to wear two Maxi-pads in future, as toilet breaks are rarely given. As the inmates become increasingly human to Piper and to the viewers, the grotesque evolves to forge new alignments and distastes, making monstrous the prison space itself, and making vulnerable the now sympathetic bodies of the inmates that it contains.

Bio:

Danielle Hancock is a postgraduate research student at UEA, specialising in audio horror forms. She has research forthcoming on the topic of radio horror drama and national identity.

References

| ↑1 | Although Piper does open her body to a sexual encounter with inmate Alex, this is in an emotionally-based relationship which precedes both characters’ prison experiences and identities; furthermore Alex’s difference from other inmates’ grotesquery is reinforced as she complains to Piper ‘GROSS FARTING’. Likewise, her beauty is reinforced throughout the show as she is repeatedly referred to as ‘the hot one’. |

|---|