‘Why publish a screenplay, when these days the finished film or TV series is so readily available? If one only thinks of them as working documents then perhaps there is little point, beyond the academic. But reading screenplays has always been as interesting to me as reading plays; an activity in its own right.’

That’s Mike Bartlett writing in the foreword to the scripts of his award-winning drama Doctor Foster (2015-2017) published by Nick Hern Books on 8 June 2017 as Doctor Foster: The Scripts. He asks a good question and gives two very good answers. As academics, you’ll know that ‘working documents’ are important – they allow you to understand the production intent of the narrative so that you can determine the creative talents that shape the finished product and understand if that ultimate programme fails or succeeds and by what criteria. I’ve commented before on how, sadly, people don’t consult the original texts when they’re available …

… but, beyond that, it’s also just that they’re missing out on a lot of fun. And fascination!

[Kim – I think that this is a good start. Mike – in addition to being kind and helpful in

my researches – is a good name as a ‘hook’] very good strong start.

I’m already interested … One of my great delights in reading scripts is the stage directions – and the wonderful words that writers employ in bringing characters and situations to life on the page. For example, here’s a sequence from Act One of The Man With The Foot, a script by Raymond Bowers for the film series referred to as Danger Man: Series II (1964-1966):

EXT. BANOLAS STREET. DAY.LOCATION. 28 DRAKE’S POV. SHOOTING DOWN TO HIS PARKED MINI, IN THE RAIN. A LITTLE FIAT, FIVE YEARS OLD, OF THE VARIETY WITH A SOFT SUNROOF, IS HALTING BESIDE IT. MONCKTON GETS OUT. THAT IS, HE PUTS A LEG OUT. ANOTHER ANGLE. GROUND LEVEL. C.S. MONCKTON. 29 HE IS THE SORT OF MAN WHO, IN PUTTING A LEG OUT TO A RAINSWEPT SPANISH BUT MADE ROAD WOULD DROWN HIS FOOT IN THE ONLY POTHOLE FOR TWENTY MILES, AND HE HAS JUST DONE SO AGAIN. HE LOOKS DOWN AT THE ACCUSTOMED MISFORTUNE WITH A SORT OF PATIENT MISERY. IT HAS ADDED LITTLE TO HIS DISCOMFORT -- THE LITTLE SOFT SUNROOF IS LETTING IN A SURPRISING AMOUNT OF RAIN . . . . MONCKTON: IS 50, OR PREMATURELY WORN, PROBABLY THE LATTER. HE IS A MASS OF QUIET APPREHENSIONS, NOT SO MUCH JUMPY FROM THEM AS RECONCILED TO A STATE OF PERPETUAL SIEGE. HIS INCOMMUNICABLE PROFESSION REQUIRES HIM TO BE CURIOUS ABOUT EVERYTHING, BUT IN HIMSELF HE IS AS INCURIOUS AS A SLOTH AND THE EFFORT OF REPEATEDLY LUGGING HIMSELF UP FROM BENEATH HIS LEAFY-SNOOZE BRANCH TO PEER AT THE INCESSANTLY MENACING JUNGLE GLOOM IS AN ABIDING EXHAUSTION. MOREOVER, HE IS CONGENIALLY POLITE TO THE POINT OF INARTICULATION, AND THIS MAKES HIM FEEL UNFORGIVABLE WHEN HE HAS TO PRY. HE MOVES IN LONELINESS, HANKERING NOT SO MUCH FOR FRIENDSHIP AS FOR SOME QUIET COMPANY TO SIT SILENTLY BESIDE IN TRUSTFUL IMMOBILITY WITHOUT IT SUDDENLY TRYING TO SHOOT HIM. HE HAS HIS FOOT IN THIS POTHOLE AND EXPERIENCE HAS TOLD HIM THAT LIFTING IT STRAIGHT OUT WON’T MAKE IT ANY LESS WET SO HE JUST REGARDS IT, WAITING FOR GOD TO LOOK ANOTHER WAY.

Furthermore, on the shooting script – as presented on the DVD set as a PDF – you can even see the production annotations… which in this case tell us that these two shots of words are planned to form 39 seconds of screen time.

And… and, and, and… some of the curated sets of PDFs on DVDs and Blu-Rays are also massively vital if you want to get the whole picture of a series, including the missing bits. Numerous editions from the monochrome era of Callan (1967-1972) are missing from the archives… but all of them can be enjoyed (sometimes in multiple drafts, allowing the reader the delight of production and narrative development) on the Callan: This Man Alone release. Ditto for some of the key escapades from the second season of Adam Adamant Lives! (1966-1967) from around the same vintage.

Oh, and don’t forget the BBC Writers’ Room with its horde of digital treasures in terms of recent works.

Even better than PDFs is actually getting to see real scripts. The BBC Written Archive Centre holds quite a few in their original form (and the remainder on microfilm for consultation). The British Film Institute is also quite wonderful for studying the development drafts of many writers, such as Troy Kennedy Martin or Eric Paice. They also have a brilliant run of the scripts to all the lost episodes of Public Eye (1965-1975) … and it’s such a shame that Robert Banks Stewart’s Memories of Meg doesn’t exist as a finished programme; it’s such a lovely read.

Sadly, not all facilities look after scripts so well. Around two decades ago, my wife and I visited a commercial vault where paperwork was retained only as a secondary item to the commercially exploitable programmes themselves. We were shown extensive files of photocopied scripts for research. They were very useful, but it was clear that in the process of copying the originals so much had been lost – camera directions, director annotations, original character names obscured by Snopake that could have been read when held up to the light.

“Thanks for your help – but it’s a shame the originals have gone,” I commented to the archivist at the end of the day.

“Yeah,” he said, “We didn’t have space for them, so we had to junk all the physical copies last year after we scanned them.”

“So what are those copies that we’ve been looking at today?” I asked.

“Ah, well, after we’d scanned the originals and had them destroyed, we figured we’d better have paper back-ups in case the electronic files got corrupted, so we printed them all out from the PDFs…” he explained… to our bemusement. And horror.

[May lose this bit] – No, keep it in – it brings up the whole issue of archives and who deems what to be useful. This is horrifying but then so were the skip loads of film stills dumped outside Elstree studies when it was sold. If you ever go to an archivists meeting it’s full of stories like this. It makes me very stressed!

Anyway… let’s not forget the academic institutes where collections have been carefully donated by their authors. A visit to the Hull History Centre gives one access to the contents of the Hull University archives, and the Hull University archives embrace the work of Alan Plater.

I’ve previously commented on the delights of Alan’s writing as it appears on the small screen, but the scripts open up new archaeological layers of bliss from his stage directions. Take, for example, his original texts for his comedy-thriller Get Lost! (1981) with its two protagonists, schoolteachers Judy Threadgold (‘late twenties, bright, eager, earnest, a friend of the Earth with a few dreams still intact’) and Neville Keaton (‘a little older than Judy, worthy, weary, a teacher of woodwork and the sawdust has penetrated deep into his soul’) and their colleague Mr Meagan (‘a middle-aged purveyor of Modern Languages and Cynicism’). Their investigations into missing persons take them to a Literary Society meeting where they encounter Herbert Doyle (‘a spiky little man, fiftyish, an undistinguished solicitor who never got over the discovery that he wasn’t George Bernard Shaw’) and Freda Moffatt (‘sees herself as Virginia Woolf, even though she doesn’t like her books […] about the same age as Doyle and wish[es she]’d been born in Bloomsbury instead of Dewsbury’).

There is also a lovely sensation of accompanying Alan as he’s writing via his stage directions. A new character is introduced in Can Anybody Join In?, the second script for Get Lost Revisited! (eventually televised as The Beiderbecke Affair (1985)) with Alan writing ‘Harry – let’s call the bloke Harry. He’s in his fifties and walking his dog is the most fun he gets in life’. And the sixth and final script concludes with the two teacher-detectives running down a Yorkshire hillside in both simulated and genuine slow motion: ‘The overall effect: Romantic, yes, and a bit daft, apparently kicking in the pants all the smartarse film-makers who slide into slow motion when they’ve run out of things to do. Essentially it’s about two grownup people rejoicing in each other’s company and a shared innocence that might be temporary but what the hell.

‘I hope that’s clear.’

[I think these are nice examples. Must watch this again. Did you ever see these Kim?]

Unfortunately not – they sound amazing!

And when you’ve done with Alan’s output, Hull also has the Stephen Gallagher collection on offer. Of particular delight here are Steve’s very earliest television scripts – so early that in 1980 he didn’t even know what a television script looked like, causing him to deliver to the Doctor Who (1963-1989) production office a hybrid novel-script entitled The Dream Time which eventually reached the screen in a revised form as Warriors’ Gate. Steve’s concepts remained intact – but much of the humour was trimmed back. The first instalment finds our Time Lord hero lured back to the crashed spaceship staffed by the dubious Captain Rorvik and his hapless crew. Shown around the helm, the Doctor is immediately curious as to why the ship’s absentee navigator needed to be manacled to his control station (the answer being that Rorvik and his men are slavers) and his hosts’ explanations are less than convincing. Then…

There’s a beep and a flashing light from the warning indicator at the helm. The rapt concentration of the moment is shattered as the bridge doors slide open and SAGAN, the self-important little ship’s clerk, comes striding in with a clipboard. SAGAN: Damage report for the warp motors, Captain Rorvik, and the men down below are wondering if there’s any progress with the plan to kidnap a Time Lord yet. . . The shrill declaration ends in a strangled gurgle as hands reach from off-screen and abruptly jerk Sagan out of the picture. Rorvik turns to the Doctor. RORVIK: Little disciplinary problem. (He nods towards the screen.) Care to come down with us and take a look?

Isn’t that fun? Of course, for Steve Gallagher-scripted stories, one doesn’t have to travel to Hull. You can just jaunt over to his blog where he’s happy to share his output from BUGS (1995-1998) to Eleventh Hour (2006) right now this minute. Fill yer boots!

[It’s okay to plug this isn’t it? Like Mike, Steve’s always kind and

helpful… and he loves Supercar (1961-1962)] yes, yes

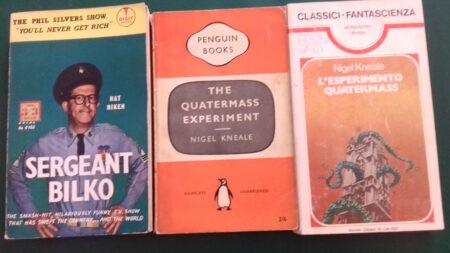

And getting back to where we started, let’s not overlook commercially published scripts. As far as I can tell, television script books began to appear in the late 1950s as TV slowly started to make its mark as an art form in its own right and not just stuff that wasn’t good enough to be made theatrically. One of the earliest examples I’ve had the delight of acquiring is Sergeant Bilko, a collection of ten scripts from the first year of The Phil Silvers Show: You’ll Never Get Rich (1955-1959). Credited to its lead writer and producer Nat Hiken, this item first made its appearance from Ballantine Books on 27 September 1957 and includes classics such as The Motor Pool Mardi Gras and The Case of Harry Speakup – the latter being, naturally, the intended text before the antics of the monkey playing ‘Private Harry Speakup’ led to a series of famous inspired ad-libs by Phil Silvers.

Across the Atlantic, November 1959 found Penguin dipping its toe into the TV script shoreline when Nigel Kneale took his serial The Quatermass Experiment (1953) and turned it into a very engaging paperback, complete with photos. Not only that, but in this form the adventure would ultimately make its way to new audiences in other lands – check out L’Esperimento Quatermass published in Italian by Arnoldo Mondadori Editore in 1978 as part of their Classici Fantascienza range.

Of course, at this juncture when you didn’t even have basic VHS technology in the home, a script book was probably the best way of reliving a highly enjoyable piece of television. Particularly when these examples of television were so early that the technology didn’t even exist for the programme makers to retain the live broadcasts in many cases. Another nice early example is Hancock’s Half Hour (1956-1960), a collection of four of the best comedy scripts from Ray Galton and Alan Simpson which were presented in a volume from André Deutsch in 1961… pre-dating the first releases of snippets of their television soundtracks in the form of Pye’s LP from Steptoe and Son (1962-1965, 1970-1974) by about a year… and way ahead of domestic ownership on tape or disc.

[Is this meandering? May lose it]

– It might not be necessary but I’m rapt …

By the late 1960s, it was wonderful to find television scripts being used for educational purposes in secondary school. Longman selected four cases from the initial incarnation of the BBC police procedural Z Cars (1962-1965) for publication in 1968 – and thus within the covers of this volume we have two missing episodes presented in script form, augmented with ‘tele-snaps’, off-screen photographs captured from the original programme by John Cura as part of an industry service of programme preservation in the pre-video days. As such, we can enjoy words and pictures for New Town incidents Running Milligan by Keith Dewhurst and A Quiet Night by none other than Alan Plater.

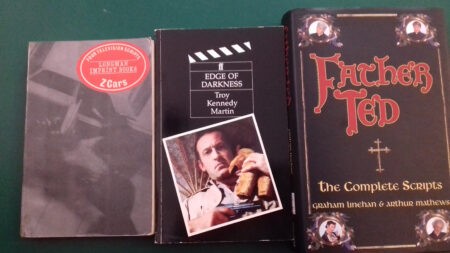

By the 1980s, we knew that television scripts were important… and if we forgot, Faber and Faber were there to remind us with their dark, serious, black-covered offerings of Troy Kennedy Martin’s Edge of Darkness (1985) or Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective (1986) which included both differences to the transmitted texts and much contextual content. Even in the video age, there were some terrific releases which opened up even the most familiar favourites; the annotated Father Ted: The Complete Scripts from Boxtree in 1999 was packed with added value over and above the original, hilarious Father Ted (1995-1998) broadcasts. Or archival items like Twilight Zone Scripts & Stories from Streamline Pictures in 1996 which offered not only George Clayton Johnson’s scripts – including Nothing in the Dark of which my wife commented “I think that’s one of the best things I’ve ever seen on television” – but also his original short stories so that his televisual translation can be admired all the more.

Original scripts and storylines also reveal the lineage and development of the TV show in other media – and being able to chart that kind of authorship and intention is vitally important in understanding the finished work. When and how did the shifts in narrative – or budget – occur? Who actually wrote those classic scenes? Credited author or contracted script editor?

Harlan Ellison’s original version of The City at the Edge of Forever – a script for Star Trek (1966-1969) that was so famous that Gary and Tony discussed it in an episode of Men Behaving Badly (1992, 1994-1998) – can be experienced before rewriting as not only a script book from White Wolf Publishing in 1996, but also as a lavish graphic novel from IDW in 2015. Up for pre-order now from Big Finish is an audio drama release of Daleks! Genesis of Terror, an adventure extrapolated from Terry Nation’s six-page outline from 1974 that eventually reached the screen in 1975 as Genesis of the Daleks. And I still strongly suspect that Leon Griffiths’ Minder novel from Hodder & Stoughton in October 1979 is a revamp of the original, darker movie treatment that inspired the successful comedy-drama which ran from 1979 to 1994 and was then briefly revived in 2009.

Even in the streaming age with almost anything available to see at any hour, the script book remains a prestige accolade for broadcasts of important television offerings such as Doctor Foster, Inside No 9 (2014-), Fleabag (2016-2019) and Staged (2020-2021).

A very exciting innovation of late has been the facsimile script – a script presented as a reproduction of the original document – from Jaz Wiseman. Jaz is a specialist collector of material relating to film series made by ITC and has, across the years, acquired specific copies of scripts that he’s keen to share with the rest of the world rather than keep locked away in his own vaults.

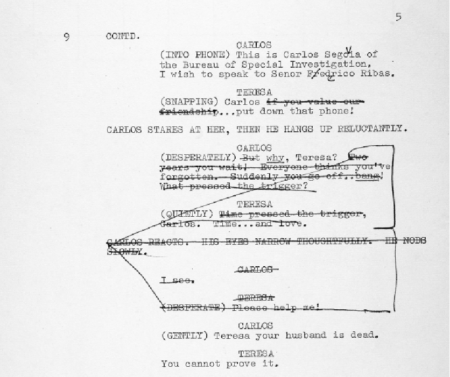

And where these scripts are doubly exciting is that they’re the director’s scripts, so you don’t only see how the author wrote (or the script supervisor rewrote) the words, but you have all the annotations of how the director brought them to the screen. I mean, here’s material from the script for Teresa, an episode of The Saint directed by Roy [Ward] Baker where John Kruse’s words have been revised for shooting:

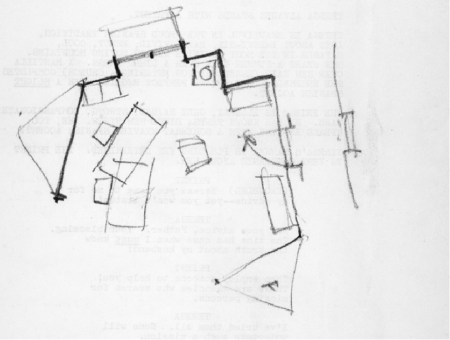

You also find Roy planning out his shots around the sets.

So – twice the value; a document with two sets of authorship stamped across it. And not only the usual stuff you’d expect such as missing scenes (notably a long sequence at the start with a bonus character omitted from the final edit), but even with the original cast listing documents thrown in as a bonus.

[Here’s how it stands at the moment Kim. Needs a bit of work and I still can’t think of a title. I know you said that it needed a decent conclusion with some true academic worth to it or a point beyond ‘You know what, scripts are kinda interesting’… yadda yadda yadda but that’s the other bit I’m struggling with. Really need some sort of running thread as a counterpoint. Oh, and I need to shove the word ‘barquentine’ in there as well for no readily apparent reason. Don’t worry, I’ll knock something together over the next week and get a new draft over to you. It’ll be with you in time.

Never let you down yet? Have I?] – No never and, for the record, I love it.

Andrew Pixley is a retired data developer. For the last 30 years he’s written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t. Blah blah blah – usual stuff. I’ll think of something related to scripts later on and chuck it in here to round it off.

Here is a handy list of British TV DVDs that have included pdf scripts of missing episodes:

Drama

A for Andromeda – all missing episodes

Ace of Wands – ten missing episodes

Adam Adamant Lives! – all missing episodes

Armchair Theatre – ‘Dumb Martian’ on ‘Out Of This World’

The Avengers – ‘Brought To Book’ and ‘Change Of Bait’ on Series 1 & 2. 14 further missing episodes on ‘Tunnel Of Fear’

Callan – all missing episodes on ‘This Man Alone’

Dead of Night – all missing episodes

Doctor Who – all lost episodes on The Lost Years CD collections

Emergency – Ward 10 – three missing episodes on Volume 3

The Georgian House – three of the four missing episodes

Hunters Walk – 11 missing episodes

The Quatermass Experiment – all missing episodes

The Road – on ‘The Stone Tape’ (original BFI release)

Target Luna – all of the missing serial on the ‘Pathfinders in Space collection’

Within These Walls – ‘Nowhere for the Kids’ on Series 2

Comedy

The Complete & Utter History Of Britain – all missing episodes

Cooper – King-Size – episode on Life With Cooper

Down The Gate – all missing episodes

Hancock’s Half Hour – all missing episodes

Lollipop Loves Mr Mole – three episodes

No, That’s Me Over Here – two episodes

The Squirrels – five episodes

Till Death Us Do Part – 13 missing episodes

Ah! Fantastic! Nice one Billy. What a brilliant list! There’s so much valuable documentation in PDF form on so many amazing DVD releases. All manner of oddities. The pilot scripts for “Sledge Hammer!” and “Whoops Apocalypse!”, all the amazing material on the “Doctor Who” discs, the different drafts on “The Prisoner”… so much to read and understand.

Many thanks indeed. Hope other people get the same thrill from these documents.

All the best

Andrew