On May 14th 2020, numerous news outlets reported on the potential closure of BBC Four at the end of the year, detailing plans for partial budget reallocation to BBC Three, as the Corporation continues to focus its attention on attracting the 16-34 demographic. The decision was taken as a cost-cutting measure in light of increasing financial pressures following the Coronavirus outbreak.[1] The news continues to generate much discussion, despite BBC’s denial, prompting consternation and reflection in equal measure across social media, with just as many outlets detailing the reactions expressed from viewers and presenters alike that the channel should be saved, and its output maintained. A Change.org petition created in the hope of reversing the decision garnered in excess of 22,000 signatures within 24 hours of the announcement.

The uncertainty brought about by the global pandemic has renewed audience interest in the Arts, reflected in the channel’s own Life Drawing Live and their comfort-led scheduling of Bob Ross’ PBS art series, The Joy of Painting (1983-1994). The channel’s impending closure feels particularly acute, accounting for some of the strength behind the disappointment and disbelief the news has provoked, as the loss of BBC Four isn’t just the loss of something to watch; it represents a significant loss to our cultural and national lives.

The demise of BBC Four, potential or otherwise, is not new. The channel’s precarious state is woven into its history, and its ongoing survival has been a continuous source of debate, contributing to wider discussions on the value of the licence fee, and the existence of the BBC as an institution. This time, the reports of its death don’t seem so exaggerated, particularly in light of Channel Editor, Cassian Harrison’s departure, stepping down to take on a programming role at BBC Studios. Though framed as a temporary appointment, with BBC Two controller Patrick Holland overseeing content across both channels in the interim, the move feels more permanent.

Fig 1: “Everybody needs a place to think” BBC Four Launch print advertisement. Source: Ben Friend.

In 2015, the future of the channel and that of BBC News was placed under a similar threat, leading to reports of reduced hours and a potential shift to an online-only model (a strategy used later for youth channel, BBC Three, from February 2016 onwards). It was estimated their closure would make the required savings of £550 million[2] in comparison to the reported £125 million now needed to cover financial losses incurred by Coronavirus.[3] Just two years later, on the channel’s 15th anniversary, Mark Lawson questioned its existence in an article for The Guardian, asking ‘What’s the point of BBC Four?’[4] At the time and in retrospect, it proved difficult to answer, with Lawson citing the combination of small audiences and a ‘confused identity’ amongst reasons why the channel may not survive into its 20th year. In light of the closure rumours, Lawson’s assessment feels eerily prescient, contributing to the now established pattern that the channel and its output are expendable.

The ‘confused identity’ Lawson described stems from the multi-faceted nature of its programming coupled with its ‘willingness to take chances and go where other channels were more cautious to tread.’[5] This combination meant it became synonymous with numerous forms of television not found elsewhere in the UK. The diversity of its output meant it could offer dedicated space for history and science programming, while also finding greater audience numbers in unexpected avenues. These range from its success with subtitled dramas including DR1’s The Killing (2007-2012) and the high-profile acquisition of prestige AMC drama Mad Men (2007-2015), to homegrown comedies The Thick of It (2005-2012) and Twenty Twelve (2011-2012).

Fig. 2: All Aboard! The Country Bus. Source: BBC Four/SlowTVBlog.

Later seasons of Mad Men would eventually be acquired by Sky after BBC Four was outbid (an early indicator of the channel’s budgetary restrictions and lack of buying power) and The Thick of it would find both a new home and a larger audience on BBC Two, yet BBC Four still found opportunities to experiment and innovate. The ‘BBC Four Goes Slow’ (2015-2016) season adopted the Norwegian trend of Slow Television in a series of documentaries dedicated to real-time journeys on busses, trains and boats. Harrison framed the documentaries as an antidote ‘to the conventional grammar of television in which everything gets faster and faster.’[6] They are also emblematic of the channel’s launch motto: “Everybody Needs A Place to Think.” By continuing to offer a place for reflection and contemplation in an increasingly fast-paced world and competitive post-broadcast landscape, the Slow TV experiment did exactly that, inspiring polarised reactions in the press and across social media, ranging from “hypnotic” and “soothing” to just plain “boring.”

Launched on March 2nd 2002 as a replacement for BBC Knowledge under the leadership of Roly Keating, BBC Four’s opening night was simulcast on BBC Two, making clear links between the former channel’s association with arts and culture programming while also emphasising BBC Four’s significant role in the BBC’s expansion into free-to-air digital television. Pre-launch press releases described the channel’s potential and diversity, positioning it as a space for a ‘rich mix of intelligent, enriching and diverse programming.’ This initial rhetoric is clearly informed by Reithian values, highlighting the Corporation’s desire to emphasise the change and innovation the channel would offer – itself a reflection of surrounding discourses on the digital turn, its potential, and the increased programming choice it would provide the audience.

Since then, the channel has largely delivered on this initial premise, particularly in relation to its arts provision, showing ballet, theatre, photography, and painting. In more recent years, it has devoted an increasingly significant amount of scheduling time to music, and in particular, rock and pop. BBC Four’s repositioning as a primary site for music programming has also become a central facet of its branding and contemporary identity, self-described as a ‘home’ for music across social media, branding, and within music commissioning guidelines. This identity is reinforced by its consistent scheduling of music programming on Friday nights – a clear acknowledgement of the established historical position of music programming within the UK schedule and the wider subcultural significance of Friday nights to music culture.

Fig. 3: Friday night music on BBC Four. Source: BBC Four on Facebook.

It’s here the loss of the channel will most keenly be felt, and by so many, including myself. The channel’s music output has become a central source for my own research over the past four years by offering an avenue through which to engage with music culture past and present. Prior to the arrival of BBC Four (and latterly Sky Arts), much of this programming survived as “best of” programme compilations and fragmentary clips on YouTube, owing to the widespread tape wiping policies before the arrival of less expensive alternatives, home viewing technologies, and stable recording and storage formats. This practice has resulted in much of this programming being lost, and as Peter Mills noted in relation to The Old Grey Whistle Test, it also means the ‘fuller identity’ of the programme as broadcast has been erased.[7]

Though music has always been part of BBC Four’s schedule, the decision to refocus has often been framed in terms of dumbing down, indicative of a perceived shift toward the popular that defined the channel under Richard Klein. However, the impact of this change in focus is more complex. As Tim Wall and Paul Long note, ‘music programming is where BBC Four’s distinctiveness is most clearly established.’[8] The increased attention to music during the tenures of Janice Hadlow and Kim Shillinglaw exemplify the channel’s consistent alignment towards difference and quality. Its distinctiveness is a positive trait, tied to underlying imperatives of the BBC’s public service ethos. Throughout its lifetime, the channel has been integral to the wider policy of arts provision on the BBC, responding to changes in taste shaped by its further democratisation.

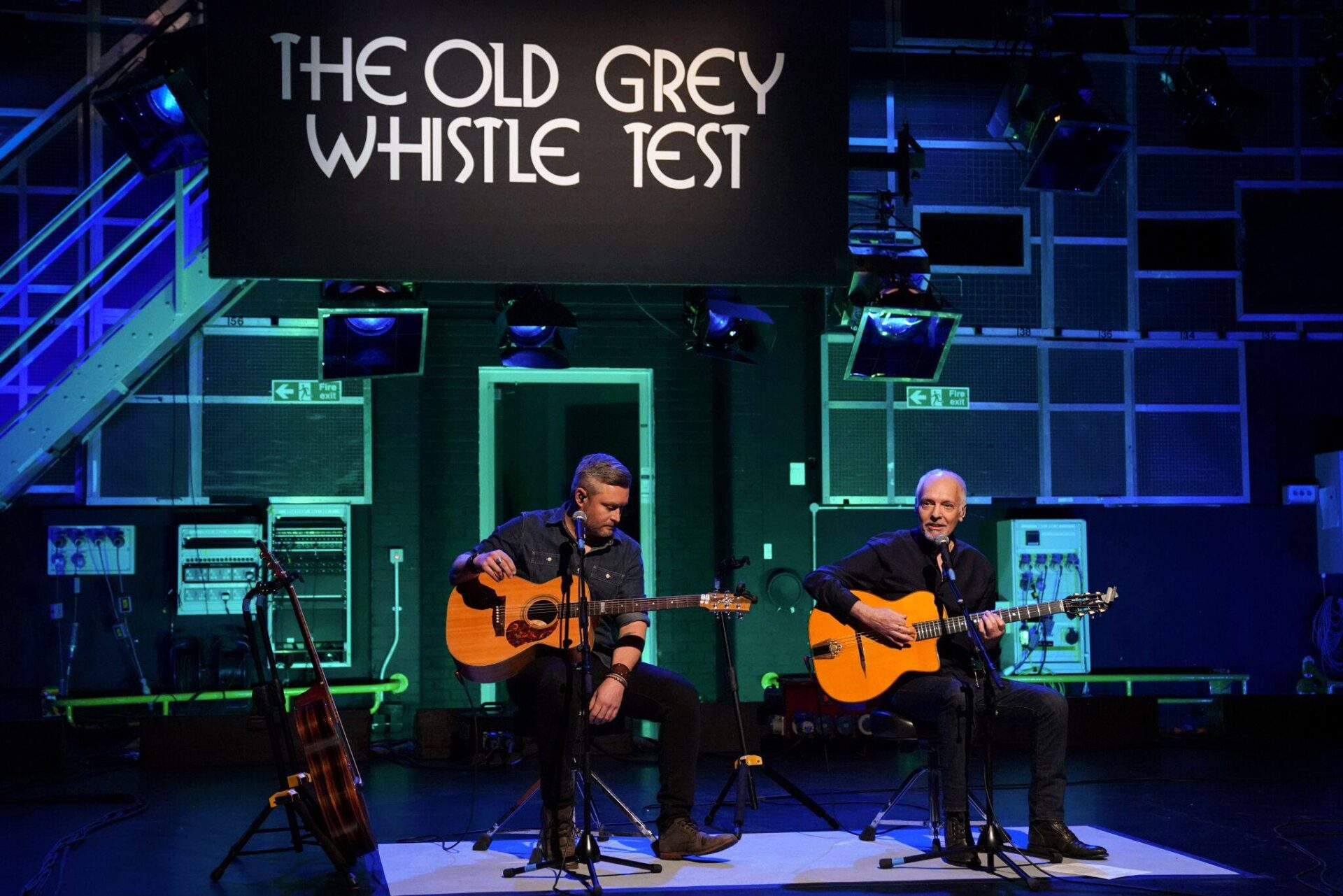

In creating a defined space for music in the schedule, the channel has drawn upon the BBC’s considerable archive resources, scheduling repeats of The Old Grey Whistle Test (1971-1988), Top of the Pops (1964-2006) and its spin-off, Top of the Pops 2 (1994 –). Commitment to music extended beyond performance to include coverage of music heritage in the Britannia series (2005 –2013) and The People’s History of Pop (2016-2017), aired as part of the BBC’s ‘My Generation’ music season (2016-2017).

Fig. 4: The Old Grey Whistle Test Live: For One Night Only (2018). Source: BBC Four on Facebook.

Outside its use of archival assets, the channel continued in its desire to innovate through its commissioning strategies, evident in celebratory specials dedicated to music past, such as The Old Grey Whistle Test Live: For One Night Only (2018) and Jazz 625 Live: For One Night Only (2019); or the recent themed evening of programming dedicated to Ready Steady Go! in March 2020. Other new commissions, including Hits, Hype and Hustle: An Insider’s Guide to the Music Business (2018) provided insights on music present, while illustrating the channel’s initial moves to appeal to a younger demographic and open up avenues for engagement with arts programming. Of these more recent successes, Harrsion’s commissioning of documentary feature Bros: After the Music Stops (2018) is perhaps the most intriguing, proving an unexpected festive hit on iPlayer, following its transmission in November 2018[9], offering a potential future direction for the channel should it continue, and Harrison return to his position as Channel Editor.

These examples, like so many I have described, are something only BBC Four could do. The success the channel has achieved through its focus on music felt like a rebuttal to longstanding claims surrounding the marginalisation and ghettoising of arts programming. In the context of BBC Four and its dedication to music, arts programming no longer felt, as Jeremy Tunstall once argued, a genre in decline,[10] and had once more found a way to thrive.

The potential end of BBC Four signals a loss greater than that of a channel. In losing BBC Four, we also lose a space that remains unique in its ambition to offer an avenue of access to and engagement with culture and ideas in a sustained manner that’s otherwise unavailable without a subscription fee. The treatment of BBC Four reiterates the damaging impact of hierarchies of value and judgment, and of mapping cultural value against economic gain. Such discourses also unconsciously reassert the dominance of drama and comedy as bankable and exportable products over that of music or arts, which in turn impacts upon what we see and hear (or don’t) on our screens.

If the channel does survive as it deserves to and continues to its 20th anniversary, what form might that take?

A potential answer may lie in the simulcast of its origins. A new home for its content could be found in BBC Two, reinforcing the longstanding dialogue between the two channels. Equally possible however, is the online-only viewing model previously initiated for BBC Three. The BBC One 10:30 pm showcase slot currently offered to BBC Three programming, including Fleabag (2016-2019) and In My Skin (2019 –) could be utilised for BBC Four, with a similar showcase on BBC Two. Such a move may not necessitate a reduced programming slate, and could ultimately result in greater audience numbers, built on our increased reliance on video-on-demand and streaming platforms, presenting a much more viable option for the channel’s future than perhaps previously thought.

No matter what the future holds for BBC Four, the channel’s many achievements, its rich history, and in particular, its valuable contribution to the Arts and arts programming should be acknowledged and celebrated. Over the last four to five years, the output of BBC Four has proven fundamental to restoring cultural value to, and raising the visibility of, music programming on television. Through BBC Four, music has been reclaimed from the pre-YouTube era dominance of MTV and the music video cycle, allowing for a return to the exploration of music as an art, built upon performance and musicianship. This will perhaps be its most enduring legacy.

In its own small but significant way, BBC Four has challenged the way we see, hear, and think about the Arts, and in doing so, how we think about the world around us. Should the channel leave our screens at the end of the year, we will all be much poorer for it. [11]

Leanne Weston is a PhD candidate and Associate Tutor in Film and Television Studies at the University of Warwick. Her doctoral research on memory and materiality in music programming forms part of ongoing work in The Centre for Television Histories.

Notes

[1] Singh, Anita, ‘Save BBC Four: Presenters Say Channel Must Not Be Axed as Corporation Plans Cuts’, The Telegraph, 13 May 2020 <https://telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/05/13/save-bbc-four-presenters-say-channel-must-not-axed-corporation/>

[2] Foster, Patrick, ‘BBC Four and News Channel Facing Axe as BBC Eyes Cuts of £550m’, 18 November 2015 <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/bbc/12004246/BBC-Four-and-News-Channel-facing-axe-as-BBC-eyes-cuts-of-550m.html>

[3] Singh, Anita, ‘Save BBC Four.’

[4] Lawson, Mark, ‘What’s the Point of BBC 4?’, The Guardian, 2017 <http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2017/mar/08/from-a-place-to-think-to-background-activity-bbc4-turns-15>

[5] Former Controller Janice Hadlow, quoted in Lawson, ‘What’s the Point of BBC 4?’

[6] Cassian Harrison, quoted in Plunkett, John, ‘Gently Does It: From Canal Trips to Birdsong, BBC to Introduce “Slow TV”’, The Guardian, 1 May 2015 <https://theguardian.com/media/2015/may/01/gently-does-it-from-canal-trips-to-birdsong-bbc4-to-introduce-slow-tv>

[7] Mills, Peter, ‘Stone Fox Chase: The Old Grey Whistle Test and the Rise of High Pop Television’, in Popular Music and Television in Britain, ed. by Ian Inglis (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2010), p. 55.

[8] Wall, Tim, and Paul Long, ‘Friday on My Mind: Public Service Television and The Place of Popular Music Heritage’, 2017, 5 <https://academia.edu/3836569/Friday_on_My_Mind_Public_Service_Television_and_The_Place_of_Popular_Music_Heritage>. Unpublished article cited with permission of the authors.

[9] Gompertz, Will, ‘Bros Film Is Surprise Christmas TV Hit’, BBC News, 28 December 2018 <https://bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-46700466>

[10] Tunstall, Jeremy, ‘Traditional Public Service BBC Genres in Decline: Education, Natural History, Science, Arts, Children’s and Religion’, in BBC and Television Genres in Jeopardy (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2015), pp. 203–44.

[11] On May 20th the BBC released its Annual Plan document for 2020-2021. In the case of BBC Three, it details plans to double its budget and the potential restoration of a linear channel, while also maintaining its online presence. Several options are outlined for BBC Four, including its role in arts education and culture programming during the pandemic, use of its archive material, potential commercial opportunities, and, as I suggested above, to show some programming on BBC Two to increase viewership. It is notable that no final decision on the channel’s future in its current form has been taken, and the BBC continues to deny reports of its closure.

Thank you *so much* Leanne. This was an excellent reminder to me to make my phone call and write my letter to say how much my wife and I value BBC Four and express our interest. Hey – we’re middle-class, so *naturally* we tend to sit here watching Lucy Worsley, “Il Commissario Montalbano”, “Borgen”, “Storyville”, Mark Kermode explaining how films work, Mark Gatiss and Matthew Sweet debating the best movie James Bond, old editions of the late lamented “TimeShift”, music documentaries from punk to Dusty Springfield, that gorgeous evening when “Jazz 625” came back to life, remakes of long lost sitcoms, the creme of “Look at LIfe”, and even Danny Baker plundering the archives for a discourse on street furniture. Goodness – I even remember thinking that “The Secret Life of the National Grid” wouldn’t hold our attention for three hours of broadcasting… and then being utterly fascinated by almost the first fact that we were presented with.

BBC Four gives us so much culturally of the kind that we used to get in the days when BBC Two was still BBC2. We do love it so very much, and we’d hate to think that it might suddenly vanish from the airwaves.

And it’s so lovely to read a piece like this and know that we’re not alone, and that there’s other people out there who value this channel as much as we do! 🙂

Many thanks – let’s spread the word!

All the best

Andrew

Thank you for taking time to respond Andrew! Just reading through your own viewing patterns with the channel illustrates how much its needed. You’ve mentioned some fantastic examples of programming here, ones that don’t naturally come to mind. The remakes are fascinating things!

It’s my hope that it if I indeed can’t survive quite as it is now, that it does do so in some form. It needs to. Now more than ever. Online viewing never does feel quite the same though does it? The relationship to the text itself and where it fits in our lives. I think it’s important to reflect on what becomes part of our daily lives and what it means to our lives to lose that, even in the potential sense. The piece I wrote definitely stems from that.

As you might gather, it’s been central to my research for many years now, but before that, it gave me access to arts and culture – things wonderful, strange and exciting – that I wouldn’t ordinarily have seen or even given the chance to had BBC Four not existed. It just happened to appear just at the right time for me, when I wanted to engage things more directly and dare I say it, seriously.

Many thanks for sharing your thoughts here with me! They speak to so many things I’ve been thinking through.

Best wishes

Leanne.

My pleasure Leanne – and I’ve flagged the piece up to a few acquaintances and posted links in a couple of places where I think you may find appreciative like-minded people.

I remember a conference back in 2013 when what seem to be retrospectively rash promises were made about the entire contents of the BBC film and videotape library being made on a platform akin to iPlayer by 2020. But I can’t really get upset by people aiming high and having neat goals – after all, at least *two* primetime drama series in my lifetime have promised me that we’d have moonbases by now… and that didn’t happen either.

But you’re right – online viewing *isn’t* the same. For my wife and myself in our particular situation, it involves cables and faff and buffering and fiddling with typing… and it’s *far* easier simply to put in the next disc of “Naked City”. But we are of an age where watching a programme “live” (i.e. on broadcast) still has a sense of occasion – the very notion of broadcast seems to bestow a value on something to our 20th Century linear minds. All very different to foraging for stuff on the worldwideweb.

I’m *so* pleased that this channel has brought you into contact with so much neat stuff which has been of use in your work… and also *so* pleased to see you convey your above thoughts with such passion and engagement! 🙂

All the best

Andrew