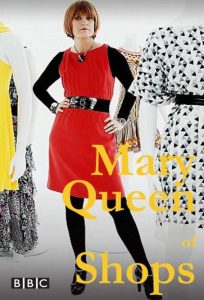

Tom Edwards has worked for over twenty years in the British television industry, specialising in popular factual and factual entertainment formats. Tom spent 15 years as a programme-maker across BBC channels, ITV, Channel 4, Five and Sky, producing popular factual shows such as the hugely influential Big Brother (C4/Five, 2000- ), contributing to the format’s experimentation with different entertainment approaches, along with more socially engaged shows like Mary Queen of Shops (BBC2, 2007-2010), Wife Swap (C4, 2003-2009; 2017) and The Undercover Princes (BBC3, 2009). Subsequently, Tom worked for 6 years as a Commissioning Executive Producer for BBC1 and BBC2 Popular Factual and Formats, finding, developing and then delivering successful new formats such as Eat Well for Less (BBC1, 2015- ) and The House that 100K Built (BBC2, 2013). As someone from a working-class background in Liverpool, Tom had an atypical set of perspectives and priorities in his commissioning role at the BBC, which was borne out in the shows that he brought to the screen.

In this interview, Tom offers insights into entering the world of television and the associated learning opportunities. He shares his understandings of television audiences and formats from professional experiences in both production and commissioning roles and discusses the connected concerns of managing talent and fostering diversity in popular factual programming.

How did you start out in television?

When I was at school and later at university I’d never considered the possibility of working in television. I had no idea about that world or how you would access it. That’s all changed now with the explosion of media and production-related courses at universities but they weren’t there to the same extent when I was moving through the education system. I studied Philosophy and Politics at university. A university friend of mine based in London happened to be temping for a secretarial agency at a TV company who were looking for runners for a Channel 4 show called GamesMaster [1992-1998]. I had no idea what it would entail but I got a call and was asked if I fancied doing this job for two weeks. Why not? So I came down from Liverpool and slept on my sister’s floor in London, got paid fifty quid a day and had an absolute riot. I could immediately see that it was an industry full of energised, driven people wanting to make things and that it would offer varied opportunities. I’d never picked up a camera in my life but in those initial couple of weeks I shot a little VT about online gaming and I was trusted to go out there and film something. So I was picking up lots of skills even in those first few days, on the production and editorial side, and it just felt like a rich vocational space to try work out what I wanted to do. Having observed the studio set-up on GamesMaster, I initially I thought I wanted to be a floor manager. Soon after, another low-level gig became available, this time for about three months, and that’s when I seized the opportunity to really start absorbing knowledge and skills and making contacts to begin working my way up the ranks. And I moved fast. As a runner for a studio, I would always go the extra mile and so made a mark. It’s also about always trying to think ahead to what they’ll want you to do next whilst you’re still working on what they want now. If you can get into and maintain that pace then you’ll move up in TV faster.

There’s such variety in TV – of content but also roles and opportunities – and there is craft in even what are seemingly the most mundane tasks. My only researcher job was writing questions for a quiz show on Sky about computing and it was the most dull show ever. However, I learnt so much about scripting from having to draft those quiz questions. For example, conciseness, the precise wording of questions so that they can have only one possible answer, questions that also work as gags, the use of visual aids, variety of tone, and so on. There’s an art to that. On that short stint I learnt a lot and it really informed my subsequent scripting work. It was exciting to realise that you could get so much out of every job.

My academic background aligned me more to the serious end of factual TV but I didn’t want to go down that route because I feel that a lot of TV documentary content – then and now – preaches to the converted. It often seems as though these shows are just telling people what they’ve already read in The Guardian, illustrating those ideas and views in quite an unimaginative fashion. So that type of programming and that type of viewer seemed over-served. I wanted to learn the dark arts of communicating with a broader audience, to furnish myself with those skills before applying those things to more serious content.

Despite working in TV, I didn’t watch vast amounts of popular factual TV until I became a commissioning editor. After working long hours, if I came home and watched something on TV I found it difficult to enjoy it as a viewer because I’d still be in work mode: it’s over-long, the premise isn’t clearly articulated, the casting isn’t quite right, and so on, so it wasn’t a relaxing experience for me to put my feet up and watch TV because it’s also my job! If I did watch TV, I’d veer towards dramas and comedies more than the factual entertainment shows that I worked on.

Something I didn’t fully appreciate initially is that TV is very delineated in terms of genre and it’s hard to move between genres of programming, so it took me some time to move over from the more entertainment-focused side of things to more serious factual. But in that shift period I worked on some great things.

What was your role in Big Brother [C4/Five, 2000- ] and what was valuable professionally about that experience?

On Big Brother I was what’s called a Story Producer. It was a great place to learn about the art of storytelling. You were working under a significant amount of pressure because of the production demands. It was a really good school. There were 7 or 8 of us and we worked on shift rotation because the schedule for turning around content was hugely punishing. You start at about 10am and watch the footage coming in and you don’t leave until about 10am the next day. You’d carry the content all the way through until the channel came in and viewed and you would hand over to finishing producers. So you’d do a shift like that about every 10 to 12 days but when not doing that you would assume other producer roles. It was just a really interesting machine for everyone involved. The storytelling process on those days when you were Story Producer was fascinating. You’d have two directors feeding you events from The House and you had to decide where the best action was and you would then direct your directors to follow those stories. You’d then take stock after a couple of hours and pull together a story. There were live loggers who would transcribe what was happening and you would pick out the threads you wanted and mark that up – the key lines that you wanted, the key moments and the key looks – sending that off to two editors whilst also keeping a handle on what was coming in next. Come the end of the day when things were getting quieter, you’d pray that housemates would go to bed early so you could spend some time stitching your show together. You’d look at all the different stories you’d had cut. If you had quiet periods in the day then you’d sometimes use that opportunity to get stories modified by editors to have them make more sense. It was a challenging juggling job of editing stories and staying across the whole show that you were putting together and staying across the live action at the time. You also needed to follow your nose – sometimes you’d need to take a punt on a particular story panning out to a pay-off – that an argument would grumble through the day and reach a satisfying climax. You’d need the confidence not to follow certain stories because you didn’t think they’d go anywhere. The show is structured around big events – eviction and nomination – so you’d know on certain days that you would need to focus on certain things. You would also pick up on particular dynamics and relationships evolving between contestants so that you could start to anticipate which stories you need to follow at particular points.

That first series of Big Brother in the UK was a fantastic social and psychological experiment, applying a particular production method to capturing what was happening. The contributors on those early episodes didn’t have any idea what would unfold and what it would be possible to capture. For example, Nasty Nick Bateman and his scheming in that first series captured something about human nature that had never really been seen before in the same way on TV. I worked on the fourth series. By then, contestants were much more aware of the mechanics of the show and saw it very much as a game to be played rather than a social experiment – something which Nast Nick had realised very early on and had been demonised for just a few years previously. By the time of series four, there was a production decision to try to take the show back to its slightly more intelligent roots because it had all become too predictable. So we selected a number of very astute, educated, thoughtful contestants and what happened is they were incredibly aware and guarded, and so you were desperately trying to draw some drama out of them. For example, romance stories died because people would feel things but agonise about whether or not they should actually communicate these things to the person they liked, and discuss them with the producers in the diary room! So it was a challenge in storytelling terms. It ultimately became an infamously boring series of Big Brother as a result. Viewers were also less savvy at that point in terms of the voting process and ensuring a good viewing experience. People were still voting to keep in contestants who they thought were good people, who deserved to win the £40k prize, rather than the ones who would make good TV, so we were left with the dullest of the bunch by the end! As a result, we brought one of the stronger characters – Jon Tickle – back in, even though he’d been voted out, as a contrivance to try inject some energy into things. However, as producers, we were told that because he couldn’t win at that point, we couldn’t lead on stories about him, we could only feature him in stories centring on others. It was a tedious directive that meant we had to turn a blind eye to stories that he was generating. It just meant that we weren’t putting the best content on screen. The production reaction to that series was to leave the social experiment roots behind and to embrace the drama, comedy and entertainment value far more.

In casting for Big Brother, immediacy is important. You need someone to leap from the screen with the right energy. There needs to be that immediate engagement with audience. Slow burn doesn’t work for a broad audience. There’s a very clear sense of storytelling and structure within Big Brother. As a viewer, you’re offered a clear sense of where you are within a series, within a week, within an episode of the show, and good contestants help with that sense of place and engagement.

What are the key things you have you learnt about audiences from your career in television?

People watch TV for different reasons. Some people seek out challenging content. Others get home from a long day at work and they don’t necessarily want to be spoon fed but they want to be helped along the way. They want it to be easy. And there’s nothing wrong with that. A lot of TV serves the producer rather than the viewer – it can be a bit of an indulgence – and there’s a space for that but there’s a snobbishness around a certain sort of TV that offers entertainment or just distraction. The trick is figuring out how to make something entertaining and not seem like too much of a challenging watch but also having that space to introduce interesting concepts or to convey messages. It’s all in the execution.

Something I became acutely aware of as a commissioning editor was the difference between that initial reaction to a show as a concept, as a title, as a cast, as a feeling about what you’re going to get from it, versus the experience of actually sitting through an hour of it. Equally, if you want to bring someone to a show, the title has to be attractive and the opening premise has to be clear or people just won’t bother. There’s an art in presenting something so that it’s appetising and seems like an easy watch but once you’ve got someone there then you can throw some more interesting things into the mix. Also, you need to build-in elements that will bring viewers back for the next episode and then the next. So it’s a real editorial juggling act.

I worked with Mary Portas on the third series of Mary Queen of Shops [BBC2, 2007-2010]. I went into that aware that it needed to change to stay ahead. It’d done fantastically well on BBC2 where the focus had been on fashion for twelve episodes but it felt like there was little else for the show to say about fashion at that point. There was a danger that it would become too repetitive at that point and fizzle out. Some key changes needed to be made and to my mind it was about the challenges that Mary faced and so I moved her out of her comfort zone of fashion and into different sorts of shops. That evolved into a broader focus on ‘the high street’ which connected to the rise in fears at that time about the death of the high street. So that all began to make sense and took on a new relevance. I felt it was crucial to underline this change in focus and scale within the pre-title of the new series, and so gave it a complete overhaul. Rather than a much shorter, Kitchen Nightmares [C4, 2004-2014] approach (‘this specific shop is awful; I need to fix it; there’ll be fireworks along the way; will I succeed?’), I opened it up much more. I set out to establish: the nature, national reach and historic scale of the problem of the death of the high street; a more solid explanation of Mary’s credentials (vital especially now she was entering a space the public didn’t associate her with); and then the specific shop, particular challenges, drama and so on. I underscored the whole thing with a very bold soundtrack – the opening ‘high street’ section used a really punchy modern electronica/hip hop cover of ‘Money’, and the first episode then used ‘Two Tribes’ by Frankie Goes to Hollywood for the episode-specific section. Tracks don’t’ come with much more dramatic welly than that! And that episode specific track was refreshed every episode.

I worked with Mary Portas on the third series of Mary Queen of Shops [BBC2, 2007-2010]. I went into that aware that it needed to change to stay ahead. It’d done fantastically well on BBC2 where the focus had been on fashion for twelve episodes but it felt like there was little else for the show to say about fashion at that point. There was a danger that it would become too repetitive at that point and fizzle out. Some key changes needed to be made and to my mind it was about the challenges that Mary faced and so I moved her out of her comfort zone of fashion and into different sorts of shops. That evolved into a broader focus on ‘the high street’ which connected to the rise in fears at that time about the death of the high street. So that all began to make sense and took on a new relevance. I felt it was crucial to underline this change in focus and scale within the pre-title of the new series, and so gave it a complete overhaul. Rather than a much shorter, Kitchen Nightmares [C4, 2004-2014] approach (‘this specific shop is awful; I need to fix it; there’ll be fireworks along the way; will I succeed?’), I opened it up much more. I set out to establish: the nature, national reach and historic scale of the problem of the death of the high street; a more solid explanation of Mary’s credentials (vital especially now she was entering a space the public didn’t associate her with); and then the specific shop, particular challenges, drama and so on. I underscored the whole thing with a very bold soundtrack – the opening ‘high street’ section used a really punchy modern electronica/hip hop cover of ‘Money’, and the first episode then used ‘Two Tribes’ by Frankie Goes to Hollywood for the episode-specific section. Tracks don’t’ come with much more dramatic welly than that! And that episode specific track was refreshed every episode.

I also felt that the episodic structure had become too predictable and Mary’s ‘character’ had become too predictable. I thought that Mary had earned the right and the loyalty of her viewers at that point to make mistakes and be seen to make mistakes, and I believed that an audience would like that and would enjoy the increased element of jeopardy. I pushed for that element of showing her making mistakes, which was made even more possible by putting her in unfamiliar territory in terms of the shop types and owners she helped.

A lot of the stuff that happens off camera would make the best stuff on camera but often producers don’t think to use it, perhaps because of this idea that it spoils the illusion of ‘an infallible expert’. But it makes for great TV and so I’ve always pushed to use those elements. There was one sequence, in the first show we recorded, focusing on a dying greengrocers. In it Mary tried to contact Sainsbury’s and negotiate some sort of partnership between them – they had a rival store nearby – and our grocers. We recorded a phone call between her and someone in PR in which they basically blew the idea out of the water. Unsurprising, given grocery sales account for so much of their business. But it was a real shock to Mary, and at the time felt like a huge set back – it had been a plan she’d wanted to roll out across the series in all the industries, partnering Big Shops with Little Shops. Her reaction was heartfelt – she was upset, and very taken aback that they could be as ‘coldly’ calculating, even with a TV camera rolling. I couldn’t make the scene work in the show in the end – narratively, it needed too much set up to do it justice, we had way too much material in the show as it was, and I just ran out of time in the edit ultimately with so much else to do. But I was really disappointed – it still bugs me to this day! The series was an amazing hit, but you can’t help but focus on the things that got away. I worked hard to do justice to that sort of content elsewhere in the series. I would always allow for and tell the story of the mistakes and challenges Mary experienced, and I was pleased with how much more credible and intelligent it made the whole thing seem. Obviously, it’s a balance – you can’t fatally delegitimise your presenter expert, otherwise viewers would lose faith and stop watching. But the uncertain outcome really helps keep people watching.

A lot of the stuff that happens off camera would make the best stuff on camera but often producers don’t think to use it, perhaps because of this idea that it spoils the illusion of ‘an infallible expert’. But it makes for great TV and so I’ve always pushed to use those elements. There was one sequence, in the first show we recorded, focusing on a dying greengrocers. In it Mary tried to contact Sainsbury’s and negotiate some sort of partnership between them – they had a rival store nearby – and our grocers. We recorded a phone call between her and someone in PR in which they basically blew the idea out of the water. Unsurprising, given grocery sales account for so much of their business. But it was a real shock to Mary, and at the time felt like a huge set back – it had been a plan she’d wanted to roll out across the series in all the industries, partnering Big Shops with Little Shops. Her reaction was heartfelt – she was upset, and very taken aback that they could be as ‘coldly’ calculating, even with a TV camera rolling. I couldn’t make the scene work in the show in the end – narratively, it needed too much set up to do it justice, we had way too much material in the show as it was, and I just ran out of time in the edit ultimately with so much else to do. But I was really disappointed – it still bugs me to this day! The series was an amazing hit, but you can’t help but focus on the things that got away. I worked hard to do justice to that sort of content elsewhere in the series. I would always allow for and tell the story of the mistakes and challenges Mary experienced, and I was pleased with how much more credible and intelligent it made the whole thing seem. Obviously, it’s a balance – you can’t fatally delegitimise your presenter expert, otherwise viewers would lose faith and stop watching. But the uncertain outcome really helps keep people watching.

The episode endings were also crucial. It was my opinion that you didn’t need to watch the last ten minutes of the previous episodes as they were so formulaic. They always steered towards this predictable pattern of Mary going to a shop relaunch, her telling them how amazingly they’d done and the horrendously clichéd shot of the clinking champagne glasses. It felt worthless in story terms. So as the Series Producer I wanted to know if they had been successful or if they were still struggling and I used that as the starting point for how we would shape the episode. But again it’s a precarious balance because viewers are coming to those transformation shows for the most-part to see a successful outcome, for hope, and so if you show too much failure then it won’t work. There’s a contract established with an audience and there are terms you have to follow to a certain extent. So you need to be careful with it but across a series there is space for the occasional fail or failed elements within a particular episode. As a result, it makes the triumphs greater. And it also connects with the realities of the high street at that time – it’s not going to work for everyone – so it seemed more honest that way.

The episode endings were also crucial. It was my opinion that you didn’t need to watch the last ten minutes of the previous episodes as they were so formulaic. They always steered towards this predictable pattern of Mary going to a shop relaunch, her telling them how amazingly they’d done and the horrendously clichéd shot of the clinking champagne glasses. It felt worthless in story terms. So as the Series Producer I wanted to know if they had been successful or if they were still struggling and I used that as the starting point for how we would shape the episode. But again it’s a precarious balance because viewers are coming to those transformation shows for the most-part to see a successful outcome, for hope, and so if you show too much failure then it won’t work. There’s a contract established with an audience and there are terms you have to follow to a certain extent. So you need to be careful with it but across a series there is space for the occasional fail or failed elements within a particular episode. As a result, it makes the triumphs greater. And it also connects with the realities of the high street at that time – it’s not going to work for everyone – so it seemed more honest that way.

In terms of persuading Mary that this sort of change is a good way to go, it’s ultimately about trust. She needs to trust that you’ve got her best interests at heart – that you’re not planning the most amazing story in which Mary implodes because she’s bitten off more than she can chew. She needs to see that you’re making changes for the sake of Mary as a brand. I came on board for series three, when Mary had already established a relationship with the producers she’d worked with for the previous series and, more broadly, with the indie making the show and the channel airing it. So I needed to prove that I had the best interests of the brand at heart and any changes were for the survival and longevity of the brand. So it was my job, as incoming producer, to win over the talent, the indie and the channel to my plan for the show. Ultimately, Mary trusted me to deliver on the idea and, as an intelligent woman, understood the logic behind the changes. She was nervous at times and felt a bit out of her depth so it was my job to reassure her. After the first episode of the third series was shot and went OK, she began to feel more confident, plus she had directors around her who she had worked with before so that helped.

In terms of persuading Mary that this sort of change is a good way to go, it’s ultimately about trust. She needs to trust that you’ve got her best interests at heart – that you’re not planning the most amazing story in which Mary implodes because she’s bitten off more than she can chew. She needs to see that you’re making changes for the sake of Mary as a brand. I came on board for series three, when Mary had already established a relationship with the producers she’d worked with for the previous series and, more broadly, with the indie making the show and the channel airing it. So I needed to prove that I had the best interests of the brand at heart and any changes were for the survival and longevity of the brand. So it was my job, as incoming producer, to win over the talent, the indie and the channel to my plan for the show. Ultimately, Mary trusted me to deliver on the idea and, as an intelligent woman, understood the logic behind the changes. She was nervous at times and felt a bit out of her depth so it was my job to reassure her. After the first episode of the third series was shot and went OK, she began to feel more confident, plus she had directors around her who she had worked with before so that helped.

I worked with the directors on the scripting and led the casting, deciding on which stories we should feature and how we should frame those stories, ensuring a mix of characters and themes and sorts of retailers that we included. I would go on location every so often – one of the 8 to 10 shooting days for each episode – but you need to resist the urge to do that too often because it can be unnerving for the presenter or the director to have a senior editorial figure breathing down their neck on location. It can be off-putting. So I need to trust in the director that we’ve had a detailed conversation in advance and that they are on board with what we need. Communication is key. When I was series producing Wife Swap [C4, 2003-2009; 2017], I was on the phone to the directors every morning and every evening to discuss plans and then what they’d achieved. Because that show was so location-based and so demanding on the directors, they needed that support and that communication, otherwise their heads would have gone into meltdown.

Dr Christopher Hogg is Senior Lecturer in Television Theory at the University of Westminster. He has published work on television drama, television acting, international television adaptation, and music in period film, in edited collections and journals such as Critical Studies in Television, the Journal of British Cinema and Television, the New Review of Film and Television Studies, Media International Australia and Senses of Cinema. His book, Acting in British Television, written with Dr Tom Cantrell, was published last year by Palgrave Macmillan, along with an edited collection (also co-edited with Cantrell), Exploring Television Acting, earlier this year. He is now developing a new interdisciplinary research project (with Dr Charlotte Lucy Smith) exploring the individual and situational factors which affect the psychological well-being of actors working in the UK television industry. He is also currently working on a monograph, titled Adapting Television Drama: Theory and Industry, for Palgrave Macmillan.

Tom Edwards has spent six years as a Commissioning Editor and 16 years as a programme maker. He commissioned for primetime BBC1 and 2, the biggest factual slots on TV, and was responsible for shows such as Hugh’s Fat Fight and formats like Eat Well for Less and The House That 100K Built. As a programme-maker he made series ranging from Mary Queen of Shops and Wife Swap through to Big Brother and The Baby Borrowers.