Like, I suspect, many of you reading this blog, I often find myself watching some kind of nature webcam. Whether it is showing views of the Earth from the International Space Station or a seaview from a coastline or a volcano erupting at a safe distance, these webcams can offer a (narrow, constructed) window on the world. Sometimes, however, those narrow windows find themselves showcasing weather, including natural disasters. As such, I have decided to focus this blog upon these phenomena — weather and webcams — and how they connect with more traditional weather television as well as create their own potential problems.

Henson (2010) provides the only book-length history of broadcast meteorology and only looks at American television. As such, making assertions about the history of broadcast meteorology elsewhere and in other media industrial contexts is difficult at best; having lived and travelled in a number of countries over the years,[i] I can say that the broadcast weather media tends to be very similar in the regions where I have been. Whether this is a direct glocalisation of an American or Western style or not is impossible to say without more extensive research. What I can say is that broadcast meteorology has begun incorporating user-generated content (UGC) much like many other media forms have. These include the subject of my blog; webcams. In some instances, webcams that have been established elsewhere will happen to be somewhere that experiences a severe weather event — traffic cameras are often used by national and local broadcast meteorologists to monitor storms in near-real time — and some are explicitly placed ahead of a coming storm to provide visual and sometimes other monitoring data from areas where it would be too dangerous to station a journalist or researcher.[ii] Those are all valid, broadly unproblematic uses — webcams have been part of scientific research for over a decade and utilising them for research or journalistic purposes that prioritise safety whilst still allowing important news, data and areas of risk to the public to be disseminated all seem to support the wider public good.

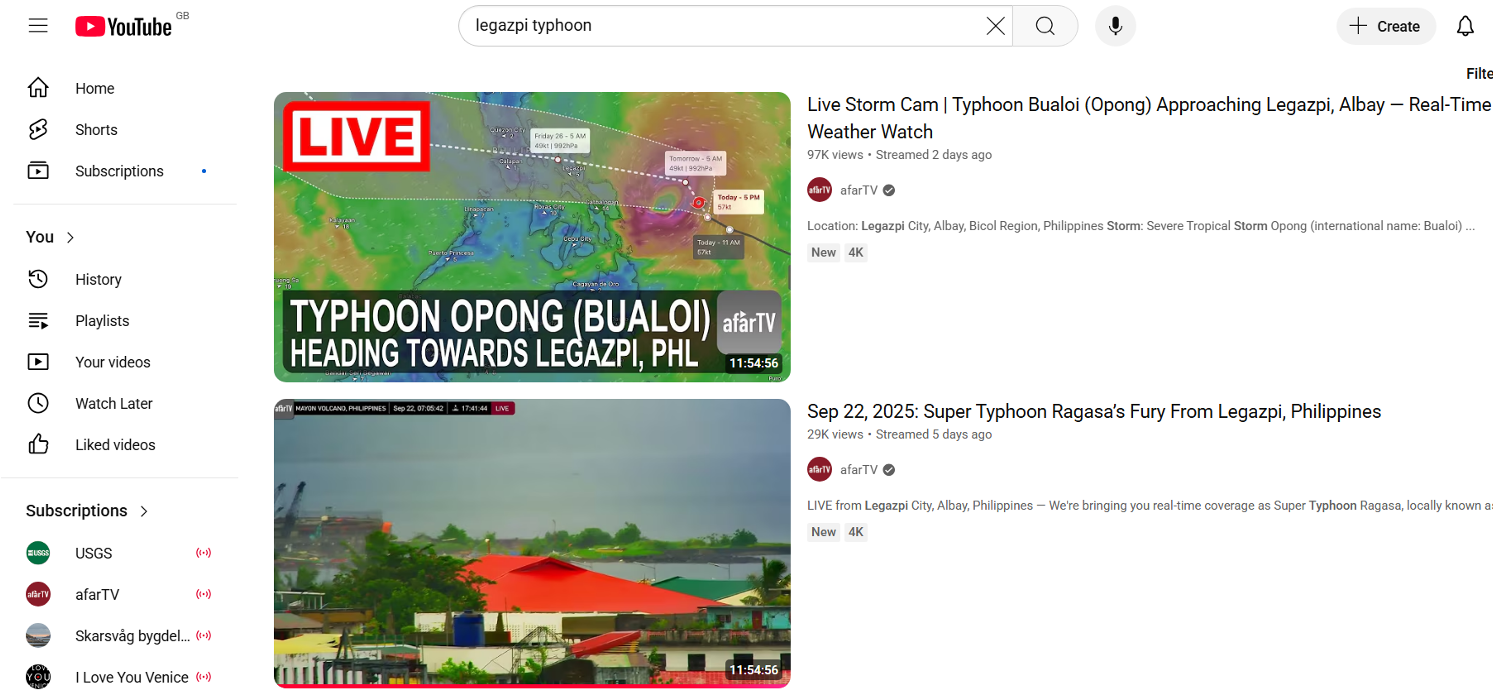

The problems, I would argue, come when an established, non-news-outlet-owned webcam’s livestream is suddenly renamed when a weather disaster is forecast. An example of this is afarTV, a YouTube channel based in Canada that is composed of webcam livestreams.[iii] A screenshot of the YouTube search page from 27 September shows the following:

A screenshot of the AfarTV YouTube search page from 27 September

AfarTV markets itself as ‘the next best thing to being there’ on its channel description. This is relevant to weather television as one of the main reasons for sending a broadcast team– or setting up webcams in advance– is to show the audience the risks of being in that situation so that the general public do not attempt to do so (Henson 2010; Beattie 2023). Whittaker and Clark (2021) writing of wildfires in Australia, note the importance of seeing a disaster or other weather event for oneself before acting on instructions to evacuate– seeing is believing, to put it colloquially. But the way in which the channel markets these two livestreams also evoke sensationalist journalism and many of the problems related to disaster tourism. The impending disaster of both storms is advertised as the draw, with the ‘fury’ of nature erasing any reference to the people and livelihoods in harm’s way. The owner(s) of the monetised livestreams is based in Canada rather than the Philippines so it is unclear if anyone directly impacted by the disaster will receive any economic benefit. This reminds us of ethical issues related to disaster tourism, including news and documentaries. While a full discussion of disaster tourism is beyond the scope of this blog about TV, Gould and Lewis (2009) note that eco-tourism in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 replicates and exacerbates the power imbalances and attendant socioeconomic and sociocultural inequalities that were already present. Tourism and rebuilding which are under the control over local elites were prioritised; while it is too soon to tell how rebuilding and tourism will play out in this area of the Philippines,[iv] virtual tourism through afarTV does not seem to benefit the impacted region. That the webcams focus upon landscape rather than people also erases the human cost from the image, even though it is perfectly valid to argue against showing people in general on a webcam for reasons of privacy.

The ‘about’ page for the channel references contact details for licensing its videos, implying that additional income can occur from selling the rights to reproduce the videos to news outlets or other digital content creators. In this they act similarly to freelance journalists such as many stormchasers (Beattie 2023). One of the findings in my pilot study on stormchasing media was that many stormchasers (freelance and associated with local/national broadcasters) felt it incumbent upon them to function as first responders when encountering people who had just been in a tornado or other severe weather event. Yet, unlike stormchasers or other field meteorologists/journalists, someone running a livestream is unable to directly help during or in the immediate aftermath of a storm. The livestreams, though having a chat function, also do not have experts in meteorology or local weather history associated with the channel. Meteorologists, stormchasers and others with relevant expertise can certainly join the chat but as far as I am able to determine, they are not brought in specially by the channel owner(s) to provide context or guidance in the way that broadcast meteorologists and/or their news outlets would do. Thus, unlike the public good impetus of journalism and science regarding media coverage of weather disasters, in this instance at least it seems as though private good (profit) is taking precedence. My pilot study showed that this was negatively perceived by stormchasing and other weather audiences; whether or not this same negative perception occurs with regard to tourism which happens to show a weather event is unclear but would be a potential area of future research.[v]

The burgeoning webcam industry that has proliferated on YouTube and elsewhere allows us to see places and events that would otherwise be unreachable due to logistical or financial limitations. During severe weather, they can provide scientific data as well as a visual record of what is happening or what has happened, potentially protecting those next in line by showing them what is coming and encouraging them to take shelter or evacuate. Yet tourism webcams can exploit our interest in seeing natural disasters by presenting them without context and by monetising them for the benefit of those unaffected. Tourism, and the travel TV that comes from it, can replicate and exacerbate the sociocultural and socioeconomic imbalances that journalism is supposed to address. While there is nothing inherently wrong with watching the weather where you aren’t, the webcam medium may not be giving you as much of the message as other media.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Dr Melissa Beattie is a recovering Classicist who was awarded a PhD in Theatre, Film and TV Studies from Aberystwyth University where she studied Torchwood and national identity through fan/audience research as well as textual analysis. She has published and presented several papers relating to transnational television, audience research and/or national identity. She is currently an independent scholar. She is under contract with Lexington/Bloomsbury for an academic book on fictitious countries and Palgrave for a book on Canadian crime dramas. She has previously worked at universities in the US, Korea, Pakistan, Armenia, Ethiopia, Cambodia and Morocco. She can be contacted at tritogeneia@aol.com.

References

Beattie M (2023)‘In it for the money, not the science?’: Problems and potentials of stormchasing media. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies, online first, https://intellectdiscover.com/content/journals/10.1386/ajms_00104_1?originator=authorOffprint&identity=33325610×tamp=20240302130115&signature=b93444144205788ba3eddbcd8180de99

Gould K A and Lewis T L (2007) Viewing the Wreckage: Eco-Disaster Tourism in the Wake of Katrina. Societies Without Borders 2(2): 175-197.

Henson B (2010) Weather on the Air. Boston: American Meteorological Service.

Potts L (2013) Social Media in Disaster Communication. London: Routledge.

Whittaker J and Clark A (2021) Research to Improve Community Warnings for Bushfire. Australian Journal of Emergency Management 13(1): 12-13.

[i] I have visited forty-seven countries as of the time of writing, and have lived for several months or more in nine.

[ii] e.g., Mark Sudduth, who has been pre-positioning cameras in advance of hurricanes in the US for several years.

[iii] ‘Afar’ in the sense of viewing something from far away rather than the Afar region of Ethiopia.

[iv] The same region was hit again by a typhoon not long after, and had recently suffered an earthquake. The Philippines are extremely vulnerable to natural disasters, particularly when exacerbated by climate change.