One of the myths shrouding the realities of US capitalism is that it is a truly private-enterprise system, with Hollywood an exemplar that is entirely sustained by its capacity to tell stories in ways that viewers pay to enjoy.

Nothing could be further from the truth, in terms of the nation’s wider economy, and its screen industries in particular.

The state is everywhere and nowhere in US capitalism. For example, commercial airlines are subsidized through the college education and military schooling of pilots who go on to work for United or Delta; post offices, telephone exchanges, public schools, airports, bus stops, freeways, and railway stations are created and sustained through the socialization of risk by governments; and the internet is a product of anxieties about Soviet missile attacks that led to the packet system of communication, developed by research schools with Pentagon subvention.

One is never physically far from the long arm of the state in the US. Military bases proliferate, college towns dot otherwise barren landscapes, ubiquitous police forces detain people on the grounds of DWB (driving while black), prisons controlled by private corporations incarcerate non-violent offenders by the score, and on it goes.

Yet the fact that public money animates US capitalism is a rarely-whispered secret in a land that madly prides itself on the phantasy that it has been built, developed, and maintained by private enterprise. Neoclassical-economics chorines, who helped generate and sustain the deregulation and income redistribution that caused the fiscal crisis, peddle such dogma in arrogant blogposts and bloated lecture halls across the country, their foundational donnée seemingly an inviolable fiction hiding as reality. But here’s the scoop: it’s bullshit.

Hollywood is supposedly the acme of laissez-faire business success, a beacon of the ability of US business to produce competitively and attract customers worldwide. And it’s a big deal. The Motion Picture Association of America, the major studios’ representative on earth/DC, says that in 2016, US screen drama was responsible for 2.1 million jobs, $139 billion in wages, $20.6 billion in indirect taxes, $134 billion in sales, and $16.5 billion in exports, thereby generating one of the biggest trade surpluses in the economy.

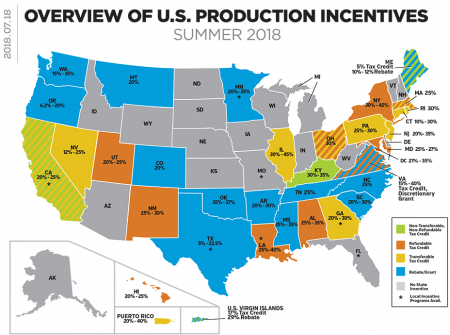

In addition to hundreds of publicly-underwritten foreign schemes and deals, TV drama benefits from domestic film commissions. Spread right across the country, they compete for producers and crews to pop over and visit, attracted by eviscerated local taxes, gratis policing, and the closure of putatively public way-fares. In 2003, just a few US states offered production incentives. By 2010, 43 of them sought to “attract” Hollywood, to the tune of $1.5 billion. Between 1997 and 2015, almost ten billion dollars was allocated. Although governments periodically cancel then revive these schemes, this decade has seen a massive overall increase in subsidies. Initially stimulated by Louisiana and New Mexico upping the ante, Georgia is the latest front-runner, providing $800 million in certified credits in 2017 alone.

The gullible governments that engage in or countenance this largesse do so for a variety of reasons, such as generating precarious jobs for the life of a TV season or series, stimulating tourism, transferring glamor to politicians, justifying the lives of culturecrats, and meeting the needs of powerful if dependent businesspeople, from producers to hoteliers.

US state governments’ incentives are often introduced as part of Keynesian counter-cyclical stimuli, but they essentially mimic fashionable programs elsewhere, and falling unemployment only occasionally brings them to a conclusive end. Public programs are said to generate ongoing investment in new infrastructure—sound stages and skilled workers, for example—that provide ongoing attractions beyond temporary direct subvention, and are acclaimed for putatively encouraging a putatively green industry.

Systems of support for TV and film production have moved from traditional forms, such as minimal credits against income tax, deductions based on losses, loan guarantees, free access to public services, and exemptions from hotel taxes, to much more expansive transferrable tax credits. A new business has sprung up in trading such giveaways. These transfers take tax credits that are afforded by governments to producers and sell them to wealthy people across the economy and country who don’t feel like paying their share of tax. In this way, producers get their money faster than they would via refunds. What began in 2009 is already a multi-million-dollar business.

While subsidy programs wax and wane with political-economic changes in state politics and financial and sexual scandals, the system in general persists. Industry magazines merrily continue to offer guides on where to get the best government deals, as the Hollywood Reporter’s map of 2018 schemes illustrates.

Negative reactions against these subsidies derive either from specific objections to support for TV but not manufacturing and farming, or opposition to industry stimulation/policy in general.

Researchers find minimal evidence that these subsidies pay for themselves in terms of private-sector expenditure during production, or the establishment of ongoing local filmmaking infrastructure. Economic and sociological evaluations of incentives across the country between 1998 and 2013 suggest that transferrable tax credits had a derisory impact on screen employment and none on wages; refundable tax credits offered no employment benefits and only contingent ones for wages; and no programs had clearly positive effects on either local media employment or the wider economy.

That evidence supports skepticism about the benefits versus the costs of tax breaks for movies as opposed to forms of longer-lasting job creation that do not have adverse effects on government receipts. It draws attention to the risk that producers who might have come to particular locations anyway suddenly enjoy windfalls at ordinary citizens’ expense. In that vein, neoclassical economics and radical political economy can agree on the importance of uncovering and problematizing state subsidies for SoCal capital.

Better results from such policies are unlikely, because of two factors: bidding contests between states, which ratchet up the terms they offer, and the longevity and desirability of the two big locations, Los Angeles and New York, as headquarters and residences. “Above-the-line” jobs (directing, writing, and acting) almost always go to LA-based people, who may be peripatetic due to state incentives, but spend most of their income—and are levied most of their taxes—far from the places where they briefly graze on location. Local workers, by contrast, are usually allocated “below-the-line” positions, as caterers and hairdressers—frequently low-paid, non-unionized, short-term, precarious jobs.

The story is one of socialism by stealth for capital, and barely-regulated capitalism for labor. Not very nice. Not very “private enterprise.” Very typical.

Toby Miller is Emeritus Distinguished Professor at the University of California, Riverside, the Sir Walter Murdoch Professor of Cultural Policy Studies at Murdoch University, Profesor Invitado at the Universidad del Norte, and Professor on the Institute for Media & Creative Industries at Loughborough University in London. His adventures can be scrutinized at www.tobymiller.org.