It’s always bloody Doctor Who isn’t it? The show about the police box that’s bigger on the inside than it is on the outside.

There is so much in the rich history of BBC drama that requires scrutiny, assessment and cataloguing, but somehow “the children’s own programme that adults adore” is the one that continues to make headlines, and the one with fans who need to know every scintilla of information about every single episode.

As a Doctor Who fan myself – mea culpa, but frankly, if it hadn’t been for many Who-nuts before me (all of whom have subsequently excelled in research into other programmes of historical importance) I certainly wouldn’t have known that the BBC held detailed production files on pretty much every Doctor Who serial produced by the corporation between 1963 and 1989. These pioneers meant that what we hitherto understood about the show was merely surface level stuff. From the paperwork at Caversham it has been possible to chart the key developments in Doctor Who’s origins and genesis and to encounter, via chits and memos and letters, the attitudes and even personalities of the many important television practitioners who have passed through the doors of the TARDIS.

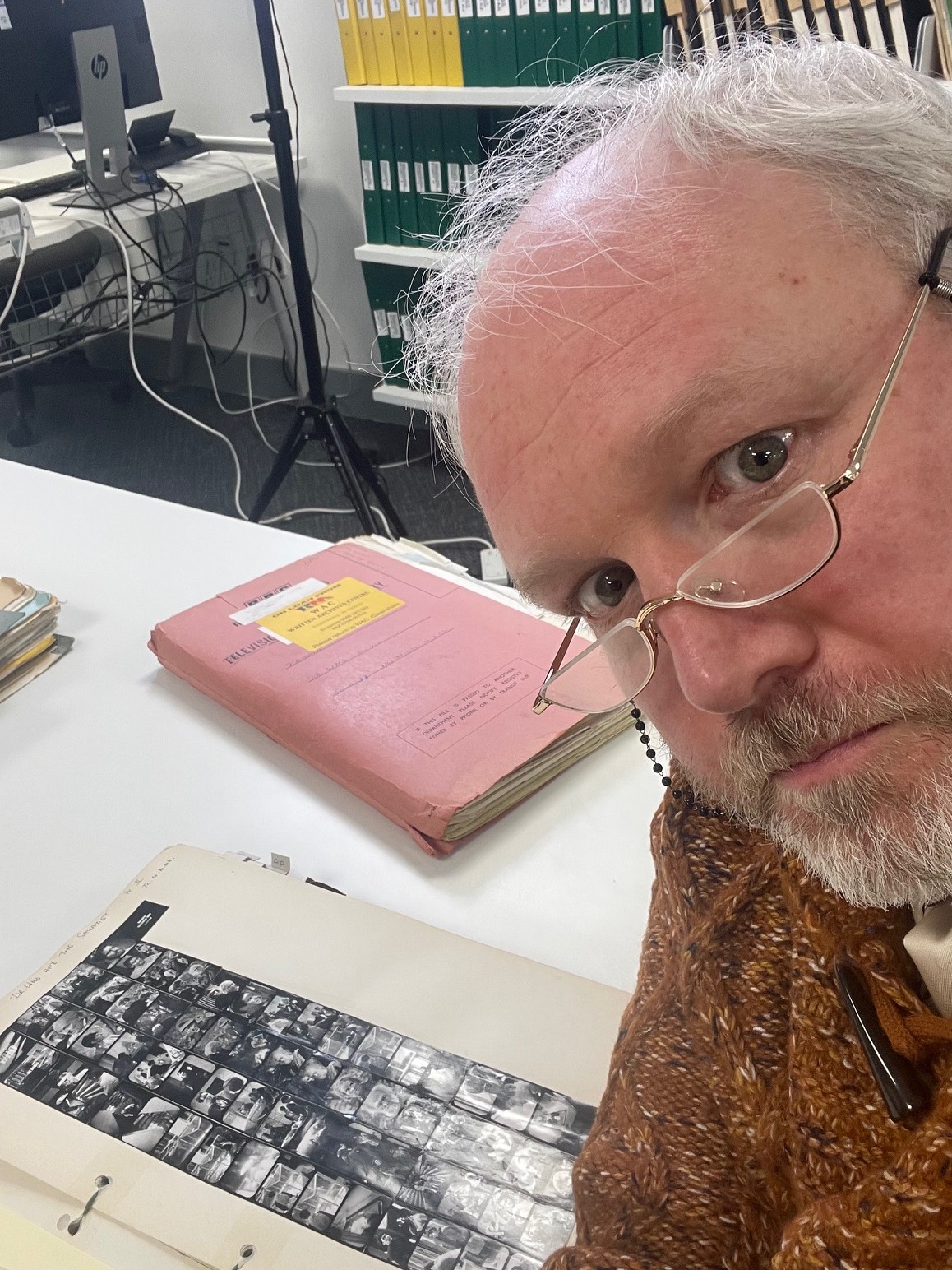

Toby Hadoke exploring the Doctor Who paperwork at Caversham

And because we have a thirst for arcana, I think piecing together of Doctor Who’s history helped a generation of researchers become fluent in the language of archive television, and gave us a proper understanding of a series that was often a reflection of the time in which it was made, and definitely a snapshot of television production techniques during specific periods.

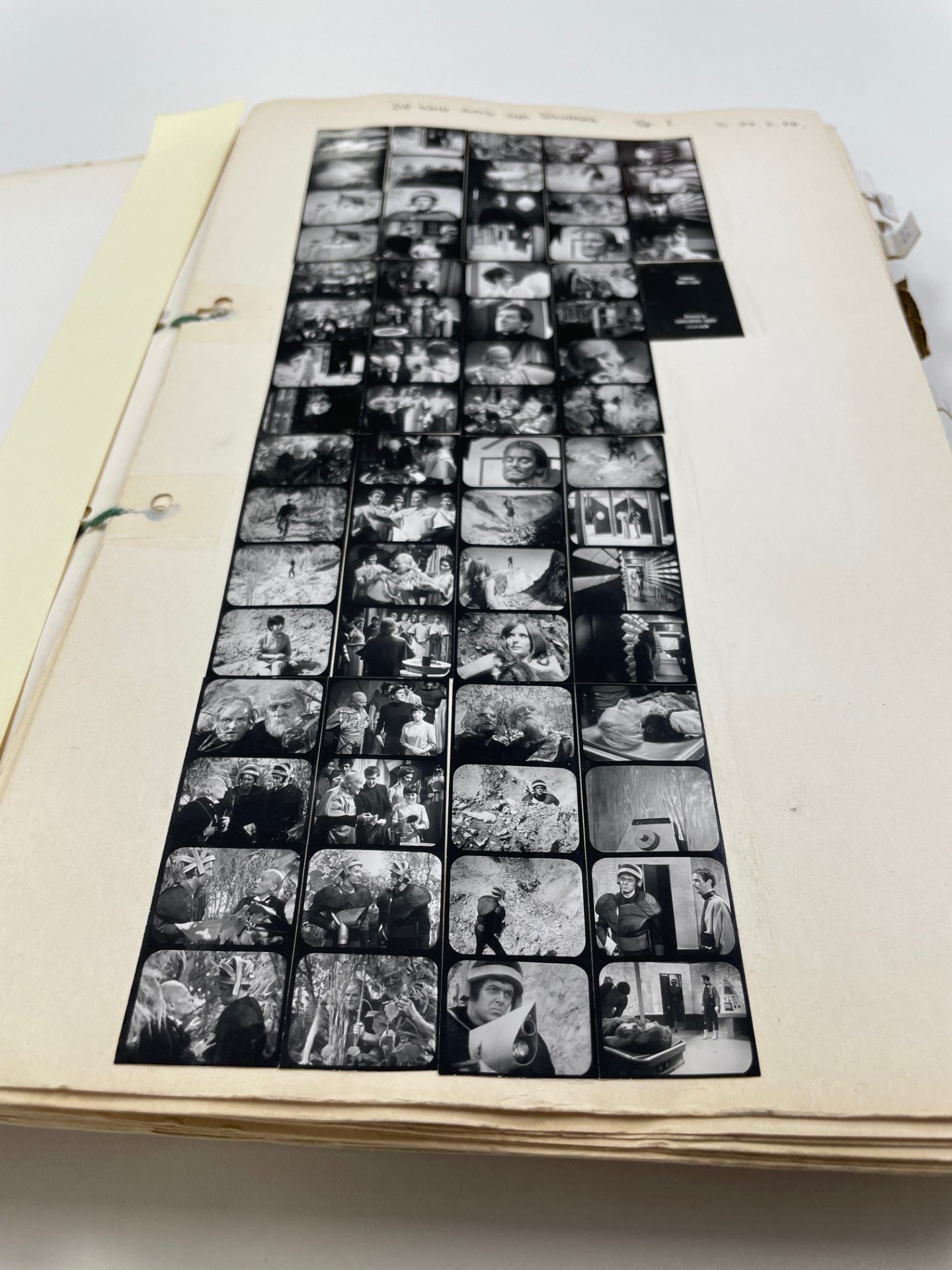

More than that, if it hadn’t been for former Doctor Who Magazine editor, Marcus Hearn, we wouldn’t have realised that telesnaps (off screen photographs of 1960s TV programmes taken by John Cura which were then offered to actors and creators as a record of their work) existed for many of the missing 1960s instalments of the programme. For many episodes, these are the only indication we have of what they looked like – and there they were, buried in the archive all that time until Hearn uncovered them. The Dead Sea scrolls carefully laid out in a cardboard file in an innocuous building just off the M4. Andrew Pixley, the doyen of paperwork sifting, wrote the definitive story-by-story accounts of the Doctor Who’s production using the riches held therein and later David Brunt, Richard Bignell, and others researching for the BBC Blu-ray range, were able to use them to extrapolate certain pieces of information or lead us to personnel who could then provide first-hand accounts that might not be covered by bits of paper.

And those, like me, who followed in their footsteps, have used their methodology to take deeper dives into Doctor Who or, more importantly, to see if other programmes were researchable in this manner. Reader, they were, and I have a 120,000 word book on the landmark 1953 science-fiction serial The Quatermass Experiment with my name on it to prove it. The files held on this pioneering production provided invaluable insight into the contents of this TV classic from which only two episodes survive (in the other archive). By having the whole of Caversham at my disposal, not just the programme’s main production file, I was able to use a combination of my own instincts, methodology employed elsewhere, and the availability of cross-referencing to solve several mysteries that had been bugging me, and to dismiss a lot of received wisdom about the serial. It took a lot of digging, a few hunches, and hours of meticulous study of diverse sources from within the archive: it may not sound very exciting to you, but the triumph of each new discovery was a feeling like no other.

Telesnaps from Doctor Who: The Savages

Doctor Who is, for many of us then, the gateway drug. It has been the programme on which we have cut our teeth, learning the ropes thanks to the BBC’s bulging dossiers and helpful staff. As time has gone on, thanks to the trial and error that is an essential part of the research process, we have discovered that – oh, that gap might be filled if I pull that actor’s file, or maybe I should check to see if there is any relevant information about this location in the file of a completely different programme that was filmed there.

Indeed one of the first things that those pioneering Doctor Who scholars discovered for us was that the series was originally devised to feature three kinds of story: the historical, in which young viewers could be informed, educated and entertained about past events; the futuristic, where they could enjoy science fiction shenanigans whilst learning about the possibilities of advancing technology; and the sideways, in which scientific concepts could be explored in an abstract way. There were very few sideways stories as it happens: they were quite difficult to conceive and realise. But “sideways” is often where research takes us. Those unanticipated and unexplored territories – those undiscovered countries – that can unexpectedly appear on the map only when we have embarked upon the journey.

Having routes cut off before we even begin is totally counterproductive to research methodology, and reduces our ability to take a sudden turn, change direction or disappear down a new rabbit hole. These are things that have definitely happened before: finding a key slip of paper misfiled in a related folder or discovering important content in the paperwork of a tangential project. This will not be possible under the new edicts introduced this year.

As Doctor Who itself has shown us many, many times, going into the past is an exciting, educational and important process, and putting barriers in our way seems such an odd thing to do after many years of extremely profitable and helpful cultural study from appreciative historians whose work rarely turns them much profit but does help to widen our understanding of the cultural landscape.

It would be a shame if The BBC Written Archive were to become, in effect, smaller on the inside…

Toby Hadoke is an actor, writer and comedian. His latest book is The Quatermass Experiment: The Making of TV’s First Sci-Fi Classic (Ten Acre Books) which is available here.