In common with the other authors of this series of blogs, I am a regular user who knows first-hand the importance of the BBC’s Written Archives. When I first visited in 2006 it was to research a conference paper on Rudolph Cartier’s 1952 television adaptation of Ansky’s The Dybbuk, an unlikely subject for a television play in 1950s Britain. The previously unvetted production file (the significance of which I can’t swear to have realised at the time) was rich and contained information unavailable anywhere else. Here, for example, was correspondence showing Cartier trying to source kaftans and stramels to give authenticity to his depiction of the Chassidic community of Biarritz. And an Audience Research Report which revealed equal amounts of appreciation, confusion and antisemitism. So began a twenty-year love affair which shows no sign of reaching anything like a conclusion and indeed won’t anytime soon. Or so I thought.

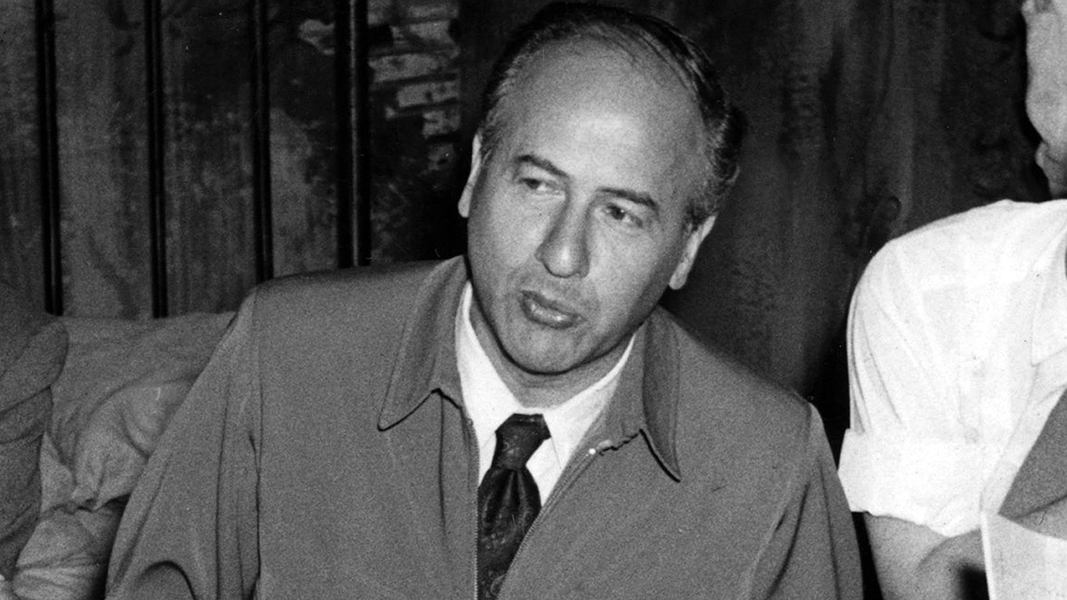

Rudolph Cartier director of 1952 TV Movie The Dybbuk

My initial research was part of a broader project to explore the BBC’s relationship to Jews and Jewishness both in front of and behind the camera and microphone from 1945 to 1979, a date chosen because of the access restrictions then in place. It was a project which some colleagues assured me would be over very quickly: the BBC was the epitome of a white, middle-class male dominated British organisation which catered for a Christian audience in which Jews played no role. But that was palpably untrue. Not only because of Cartier but such figures as Paul Fox, Brian Tesler, Ronnie Waldman and Stephen Hearst. Or looking further afield there was Harold Pinter, Jack Rosenthal, Wolf Mankowitz, Jacob Bronowski, Sid James, Yvonne Mitchell… And the first guest on Desert Island Discs was, after all, Vic Oliver.

In trying to piece this convoluted relationship into a coherent narrative the Archive was, and is, essential. Unique. The jewel in the crown. A place where one can learn about individual and institutional attitudes as well as confirmation of transmission times and viewing figures, contemporary reactions through the seemingly endless supply of near identical boxes of newspaper clippings and audience research reports which never fail to inform, educate and, indeed, entertain.

The Holocaust has always been an aspect of this work and here again, although not an archive about the Holocaust, one finds that WAC fills gaps, often gaps which some never knew existed. Scholars have been this way before (one thinks of Jean Seaton’s work and Michael Fleming’s detailed scholarship on Auschwitz and the censorship of what was known) but still within the field of popular British memory and the Holocaust there is really only one fact which persists re the BBC: that Richard Dimbleby’s broadcast from Belsen in April 1945 was the first time that the British public learned the full horror. Putting to one side the significant fact that Dimbleby’s broadcast was not transmitted in full and the sole reference to Jews was edited out from the very short extract broadcast that evening, what became clear after even a short time at WAC (this was before Genome and the Programme Index) was that there had been many programmes which engaged with the persecution of European Jewry before and after 1945 on both radio and even pre-war television. At WAC, for example, I was able to learn more about the edition of Guest Night (BBCtv, tx. 6 March 1939) which was devoted to ‘The Refugee Problem’, including interviews with Sir Henry Bunbury of the German Jewish Aid Committee and a German Jewish nurse who had fled Germany and was now living in the UK. The studio discussion was complemented with films shot specially which included children from the Kindertransport arriving at Liverpool Street Station.

I have not always been the first person to request access to the files I need for my work, but each strand of work has inevitably taken me in new directions, directions which require leads to be followed and files opened. This means that any one file is simply the start and such is the richness of the archive that one cannot always predict the next step. Contributor files lead to production files and left staff files; similarly left staff files lead to production files and contributor files. It is about the whole. Each file tells only part of the story and it is only time and with the help of the knowledgeable and dedicated staff at WAC that one begins to understand the workings of the archive and with it the richness and value of the BBC. But now the Corporation’s memory is to be curated, with access and independent research curtailed for many and limited for most. This is not what any responsible archive should be doing, and especially not one of such globally recognised importance. There is a sense of duty incumbent upon any organisation which holds public records to make those records public upon request. The promised macro release of material is imminent and may provide a way forward, but we still have no sense of what that will be. And if, as Andrew Pixley’s 2023 post made clear, there is no requirement that files be vetted for internal use, what is driving the release aside from external demand? What would help is a catalogue which shows what is and what is not already available. This is not a new observation as the need for an online catalogue has been discussed for as long as I have been going to WAC. For now though the road not taken is blocked, at least partially, and while the past has been secured, it has an uncertain future.

James Jordan is Professor of English at the University of Southampton and Director of the Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations. He has published widely on the history and memory of the Holocaust in film, radio and television. He is currently writing a monograph on the BBC and the Holocaust.