Siegfried Kracauer in Theory of Film describes the strangely transporting effect of memory while watching old documentary films containing recognisable childhood objects. A sudden distraction is triggered by filmic images that Kracauer identifies as ‘invisible conduits’[1]. Watching these remembered objects is at once alien and familiar, producing a range of emotions which juxtapose the present and the past. The spectator is simultaneously watching the film, remembering their own past, and noting the difference between their earlier and current state.

Watching Season 3 of The Crown (Netflix 2016-2023), I note with amusement the casting of Sam West, the son of Prunella Scales, as Anthony Blunt. In 1988 I was the Staff Director on Single Spies at the National Theatre: a double bill of Alan Bennett’s An Englishman Abroad, along with a new play, A Question of Attribution, about the recently exposed member of the ‘Cambridge spies’ Anthony Blunt (Bennett), the surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures. The show caused controversy because it featured a scene where Queen Elizabeth II (Scales) has a conversation with Blunt about an enigmatic painting in the corridors of Buckingham Palace. Blunt has discovered an earlier Titian painting underneath the surface, and their conversation examines secrets hidden in plain sight. The script surreptitiously listed Scales’ character as ‘HMQ’ and as I recall, there was uproar amongst the board of the newly renamed ‘Royal National Theatre’, who were very nervous of how the play might offend the palace. Prunella Scales, interviewed years later by the Independent, said, ‘It was the first time that a reigning monarch had been played on stage. Playing at the Royal National Theatre gave it an extremely powerful `blasphemy factor’’[2]. The tabloids were outraged at Sybil Fawlty (Scales’ character in Fawlty Towers) portraying the Queen, suggesting that it was bordering on treason.

I tell this story to illustrate how my lived experience impacts my viewing of The Crown. The scene of Queen Elizabeth (Olivia Colman) questioning Anthony Blunt (Sam West) over the political affiliations of Harold Wilson bears a strange resemblance to Bennett’s play. The surface conversation is again prompted by an enigmatic painting and is seemingly mundane. Yet in the two-shot camera positioning – with Elizabeth in focus at the forefront and Blunt out of focus behind (Fig. 1) – the spectator sees vague realisation dawning upon the Queen that Blunt may have personal knowledge of Soviet recruitment of Left-leaning British men.

Feminist literary criticism has richly explored the process of doubling a present vision with a ‘radical alteration’[3], whereby the female spectator draws upon her political, social and cultural perspectives to inform her viewing. Isabelle McNeill writes that film is ‘a kind of skin formed on the surface of real experience’[4], noting the ability of cinema to draw upon the spectator’s memories, melding together the past and present: recognisable images trigger emotional responses, existing like a ghost version of reality. In this instance, I am watching a fabricated dramatisation of real historical people, that has echoes of a stage play, drawing upon my own memories that are triggered through the situational placing of the actors in the frame. The effect is akin to a palimpsest, as McNeill has suggested, whereby my interaction with the televised series is a ‘dynamic reconstitution’[5] with past experiences brought to life, rather than a simple recall of archival facts. This is an interesting springboard to consider how layered spectatorship features in historical reenactment, particularly The Crown, where great effort has been made to visually connect documented images with their fictional representation.

Reconstructed Events

Pam Cook points out that contemporary use of historical events in post-modern arts aims to bring the spectator closer to the past, producing ‘a kind of second-hand testimony that includes the audience as witnesses to reconstructed events’[6]. The Crown’s storylines make use of known occasions where the royals were photographed in public, alongside imagined private conversations. As Morgan told the Royal Television Society, the narrative of the series was always going to be structured around a framework of royal events, as ‘where they go and what they do are a matter of public record, so we sort of know where they are at a given time and what they are doing in the given time’[7]. In fact, marketing of the show on social media reveals how Netflix invites the audience to draw comparisons between the real events and their fictional counterparts. Tweets from the @TheCrownNetflix (Fig. 2) place the images side by side, while excerpts from the series play alongside original video footage. The catchphrase ‘It’s all in the details’ suggests that a primary focus of the tweets has been the accuracy of the copies, with hair, make-up and costume enhancing the actors’ mimicking of expression and posture.

It is interesting that in the tweets above, the real images are brighter, making them appear to have been colour enhanced. In contrast, the photographs from The Crown look muted, duller, with a dark filter and therefore more believable, as if they have not been doctored. The tweets emphasise the importance of audience recognition of the original images, relying upon culturally iconic fashion (Diana’s llama jumper, her revenge dress) to trigger memories, while not presenting an exact mirror image of the events. Robert Lacey, the show’s historical consultant, insists that The Crown is not aiming for accuracy: ‘We’re not pretending this is a chronological record of those years. There are lots of documentaries that do that sort of thing. This is a drama which picks out particular objects’[8]. While Lacey is keen for the audience to pick up visual cues that fix the characters in a specific time and place, Mareike Jenner is critical of the show’s reliance on such props, suggesting they pander to a transnational television audience[9]. Instead of casting a critical eye on the unique political aspect of the British royals’ power, Jenner argues that The Crown fulfils global spectators’ desire for nostalgia, with clothing, hair and makeup acting as conduits. By triggering remembered imagery and splicing them with fabricated dialogue, The Crown produces a simulacrum of history, one where the spectator’s personal experience of the past merges with their current viewing.

Shared Cultural Codes

Watching Seasons 4 and 5, which portray the arrival of Diana Spencer, feels infused with the weight of the present upon the past. Peter Morgan acknowledges the difficulty in writing storylines involving Diana, likening her memory to haemophilia: ‘if you just touch it, it bruises’[10]. The sense of a pre-destined tragic outcome haunts the depiction of events from the 1980s onwards. Stuart Hall writes of two definitions of the term ‘cultural identity’ – the first refers to collective ‘common historical experiences and shared cultural codes’ providing stable frames of reference and meaning[11]. In many ways, The Crown relies upon a sense of shared cultural history. The audience are given signposts to acknowledge this understanding – Diana roller-skating alone in Buckingham Palace before her wedding day, Charles exasperatedly condemning her for showing off after the ‘Uptown Girl’ dance with Wayne Sleep at the Royal Opera House – to build towards the storyline of her shocking death in the Paris tunnel (the Season 6 opener). Critics and academics have drawn attention to how, without personal recollection of the events, young women interpret her story as resembling a fairytale[12]. The framework for the young female spectators’ interaction with Diana is that the Princess was wrongly treated by the royals, humiliated by her husband, hunted by the press. While previous seasons relied on bringing illumination to little-known events in the royals’ lives, The Crown Seasons 4-6 would be a very different experience without the spectators’ awareness and recognition of key events that build the story of betrayal.

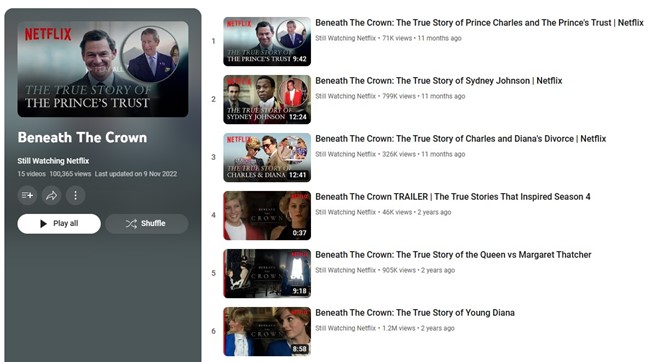

I teach at an all-girls independent senior school and so I asked my students how they feel about watching The Crown – a show where there are imagistic references to events that their parents’ generation would recognise, but they might not know about. What do teenagers do when they know there is a cultural reference that they don’t get? The students said that if they sense that there is an Easter Egg, they will go to an online forum to check, obtaining further information and quite often a link through to the original reference point. Unlike my instant flash of memory, these young women are manually forming image connections by filling gaps in their lived experience. My students’ favourite site is the YouTube series Beneath The Crown (Fig. 4), which examines key moments in the lives of the royals, mixing historical video and newspaper coverage with scenes from the show.

Created by Sophie Williams, former Global Leader at Netflix, and presented by Anita Rani, the videos were commissioned in response to the high demand for more in-depth information on the events shown. Williams refers to the Beneath The Crown episodes as ‘deep dive’ videos, aiming to keep curious viewers within the Netflix realm[13]. By narrating ‘the true story’ of the royals as prompted by the series, Netflix consolidates the accuracy of events depicted on the show. I am reminded of Angela McRobbie’s concern that young women have traditionally been persuaded by consumer culture through advertisers exploiting their ‘pervasive insecurity’[14]. This co-dependent relationship between Netflix and YouTube feeds upon the sense that lack of first-hand experience can be quickly resolved, allowing younger viewers to perceive the narrative of the series as confirmed by transmedia storytelling.

Nostalgia and Fake News

The Crown spectator generally accepts that the series incorporates some events which are based on documented evidence (transcripts of interviews and speeches, filmed footage), some rely on second-hand testimony (biographical accounts, insider knowledge) and some are pure fabrication (most of the dialogue). This separation enables the spectator to navigate the series with an open mind about its veracity. However, there are times when the series deliberately manipulates established indicators of accuracy, creating confusion over attribution. Alongside recreations of archival footage, The Crown has incorporated real footage which appears to consolidate fictional ideas. In Season 5 Episode 3 ‘Mou Mou’, actual footage and audio of film producer David Puttnam accepting the 1982 Oscar for Chariots of Fire is used. In the clip, Puttnam thanks ‘Mohammed and Dodi Fayed who came through for us and put their money where my mouth was’. This is bookended by dramatised scenes of Mohammed Fayed watching the award ceremony on television in his Paris home and confirms his desire for recognition amongst the British establishment. Placing the real footage (Fig. 5) alongside a fictional narrative confirms the scripted view of Fayed as menacingly determined to inveigle his way into royal circles. This wilful suspension of disbelief is accepted when footage is recreated, but jars with the inclusion of archival film, edited to support a fictional storyline.

Peter Morgan has said in an interview with the Royal Television Society that his dramatic creations of scenes are an attempt to ‘get the dots to be closer so that me joining the dots becomes less an act of fantasy and more an act just of the imagination’[15]. Perhaps the heavily criticised Season 6 episodes depicting Diana’s death, and the rather unexpected appearance of her ghost, has the opposite effect of layering, jolting the spectator out of nostalgia. In certain scenes – the spectral Diana thanking Charles for his behaviour in the morgue; Diana’s ghost urging the Queen to continue and offering advice on how to be more approachable (Fig. 6) – The Crown crosses the line from interactive history to the literal depiction of imagination over fact. At these moments, the series reveals how close fictionalised history can be to fake news, and the layered spectatorship is unravelled.

Ryan Lizardi notes that through the wide availability of historical filmed material and the technology to engage with brief images, spectators are able to construct a personalised and radical view of the past – ‘History is now about what we loved and consumed, not what happened to us as a culture’[16]. Because of programmes such as The Crown, public figures from the past are layered with contemporary values: Queen Elizabeth II has been identified as ‘the ultimate feminist’[17] by the actress Olivia Colman. The royal family are a unique subject for considering this palimpsest effect as they do not officially confirm or deny the veracity of events, so there is a gap created between autobiographical accounts and creative explorations. As we move further and further away from the memory of the original historical events, I wonder how The Crown will be perceived by the audiences of the future.

Leona Heimfeld is a mature PhD student in Film at Exeter University. Her subject is ‘Contemporary Modes of Spectatorship: Netflix, young female viewers and the impact of the lockdown experience.’ She has been Head of Film at Northampton High School and is currently teaching at Bedford Girls School. Prior to teaching, Leona was a theatre director at the Royal Court, Royal Shakespeare Company, National Theatre and Artistic Director of Polyglot Theatre Company. Leona has presented conference papers on ‘Pause as Progress’ at Kings College London (June 2021), ‘Cancelling the Male Gaze’ at Fandom Post-#MeToo in Paris (July 2022) and ‘Visual Displeasure: Hate-watching ‘Emily in Paris’ at the University of Exeter (March 2023). Her article ‘Press Pause: Distracted Spectatorship in the Streaming Era’ has been published in the October 2022 issue of Makings journal. She can be contacted at lh715@exeter.ac.uk.

Footnotes

[1] Kracauer, S. (1997) Theory of Film – The Redemption of Physical Reality, Chichester: Princeton University Press. p. 56.

[2] Rampton, J. (1997) ‘Queen of Parts: Profile, Independent online. 1 February 1997. Available at: QUEEN OF PARTS: PROFILE | The Independent | The Independent

[3] Showalter, E. (1975) ‘Literary Criticism’ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Vol. 1. No. 2. P. 435. Available at: Literary Criticism (oclc.org)

[4] McNeill, I. (2012) Memory and the Moving Image – French Film in the Digital Era. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p.31.

[5] ibid p.25.

[6] Cook, P. (2005) Screening the Past – Memory and Nostalgia in Cinema. London: Routledge. p. 2.

[7] The Crown’s creators discuss making the hit Netflix series | Royal Television Society (rts.org.uk)

[8] Halleman, C. (2022) ‘Is The Crown Accurate? The Answer is Complicated’ Town & Country online. Oct 5, 2022. Available at: Is ‘The Crown’ Accurate? – Fact-Checking What The Crown Gets Right and Wrong About the Royal Family (townandcountrymag.com)

[9] Jenner, M. (2021) ‘Netflix, nostalgia and transnational television’ Journal of Popular Television. Vol 9 number 3. Pp. 301-305. Oct 1, 2021. p303. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1386/jptv_00058_1

[10] The Crown’s creators discuss making the hit Netflix series | Royal Television Society (rts.org.uk)

[11] Hall, S. (1989) ‘Cultural Identity and Cinematic Representation’ Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, No. 36 (1989) pp. 68-81. P. 69. Available at: https://www-jstor-org.uoelibrary.idm.oclc.org/stable/44111666

[12] Coughlan, S. and Rosney, D. ‘How The Crown could undermine the crown for young audiences’ BBC News online. Nov. 8, 2022. Available at: How The Crown could undermine the crown for young audiences – BBC News

and Cosslett, R. ‘Young women are watching Diana’s story in The Crown with horror’ The Guardian online. Nov 24 2020. Available at: Young women are watching Diana’s story in The Crown with horror | Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett | The Guardian

[13] Williams, S. Netflix, Beneath The Crown – The Royal Documentary – SOPHIE WILLIAMS (sophiewilliamsofficial.com)

[14] McRobbie, A. (2008) ‘Young Women and Consumer Culture – An intervention’ Cultural Studies, 22:5, 531-550. p. 535. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380802245803

[15] The Crown’s creators discuss making the hit Netflix series | Royal Television Society (rts.org.uk)

[16] Lizardi, R. (2014) Mediated nostalgia: individual memory and contemporary mass media. Lanham: Lexington Books. p. 5.

[17] Cox, E. (2019) ‘The Queen is the ultimate feminist’ Olivia Colman never gave the monarchy a second thought – but now she’s playing Her Majesty, she’s fallen in love with her royal role model’ Radio Times Nov 12 2019. Available at: https://link-gale-com.uoelibrary.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/A605551487/ITOF?u=exeter&sid=bookmark-ITOF&xid=7b4bf613.