So far in our blog strand, we have been looking at moments of performance that are quite noticeably (if not obviously) about performance in some way, where the actor demonstrates an impressive level of skill via their use of their own body (Robert Lindsay’s twitch in G.B.H. (Channel 4, 1991)) or an unusual prop (Charles Dance’s skinning of a deer stag in Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-present)). Today, we wish to pay attention to something that is often overlooked, but no less impressive – in fact, something that, when done well, is easy to overlook, because it becomes ‘invisible’ (see Naremore 1988, 17). And we wish to pay attention to how this something is done well by an actor whose haircut, toned arms and high-profile marriage, divorce and subsequent personal life have received a considerable amount of scrutiny, but where little in-depth attention has been paid to what that actor actually does when she acts. That actor is, of course, Jennifer Aniston.

Our interest lies not with the significance of Aniston’s star persona and ‘synthetic media stardom’ (Johnson 2012, 62) – see Susan Berridge’s (2014) and Victoria E. Johnson’s (2012) illuminating discussions for these – but with a particular detail of her acting, which we were vividly reminded of when catching some of the reruns of Friends (NBC, 1994-2004) last summer for that show’s twentieth anniversary celebrations: Jennifer Aniston listens and reacts impressively well – in actor discourse, this is called ‘acting off the line’. Examples of Jennifer Aniston’s ability to act off the line can be found abundantly in Friends; and we shall narrow our focus to the episode ‘The One With the Kips’ (5.05), and specifically the scene when Ross (David Schwimmer) tells Aniston’s Rachel (who received the news that her family’s dog Le Poo died shortly before) that his new wife Emily (Helen Baxendale) demands that he does not see Rachel anymore. (This scene begins roughly halfway through the episode; 11.43 on the ‘Extended, Exclusive & Unseen’ box set DVD.) The way in which Aniston deals with the scene from the moment she hears this news until the point when she leaves the apartment deserves to be unpicked in some detail, for Aniston here acts off the line by managing to seamlessly play four different verbs in order to achieve her objective within this unit of text.

For readers less familiar with the above terminology, ‘verbs’, ‘objective’ and ‘unit’ stem from a Stanislavskian approach to acting that – (in)famous for its unstable terminology (and spelling of the name Stanislavski) – is located within realism/naturalism, emphasising the inner life of a character and the truth and believability of the character’s portrayal. A unit (also sometimes called a ‘bit’) is a segment of the play text (or script) that ‘embodies a single action and begins whenever the action of the scene shifts’ (Carnicke 2010, 15). Stanislavski insisted that:

At the heart of every unit lies a creative objective. … Every objective must carry in itself the germs of action. … You should not try to express the meaning of your objective in terms of a noun … but … always employ a verb. (1963 [1924], 103; emphasis in original)

With an objective being a specific goal that a character wants to achieve in a unit, the Stanislavskian approach enables actors to find a personalised route through the script and their own interpretation of it, helping them to find specificity and nuance. The emphasis here is very much on the route rather than the destination or end result, with Stanislavski being a firm advocate of the following view:

The mistake most actors make is that they think about the result instead of about the action that must prepare it. By avoiding action and aiming straight at the result you get a forced product which can lead to nothing but ham acting. (Stanislavsky 1964 [1937], 117)

With an objective to give herself time needed to process Ross’ news alone, Jennifer Aniston’s route through the scene in question and the verbs that she chooses to play map out as follows: immediately upon hearing the news, Aniston’s Rachel takes a moment to process the content of what she has heard, and then amusedly expels breath and stamps her foot. Keeping her arms crossed, she verbally responds with the words ‘Well, that’s crazy; you can’t do that. What are you gonna tell her?’ Here, the way in which she physically is keeping this news outside her body (including via means that would not be visibly captured within the medium shot, namely her stamping her foot), constructs an organic, spontaneous reaction that deflects the information she has received.

Deflecting

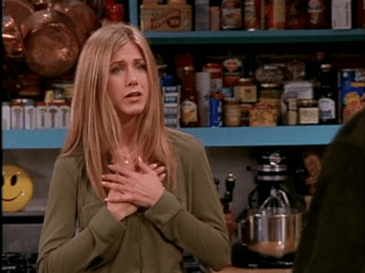

Then, when deducting from Ross’ embarrassed silence that he has already agreed to Emily’s demand, Aniston is physicalising the verb ‘to realise’ by moving her hands to her chest after a beat, letting the news to her body. The slight delay in this suggests that her character needs a moment to take in the enormity of the information, and the quality of her hand movement (which is quite firm, producing an audible ‘smack’) reflects that the weight and pain entailed within this news is now approaching her.

Realising

Backing away from an entreating Ross and withdrawing into herself for a moment, Aniston’s Rachel snaps out of her stunned state upon hearing Ross’ scant consolation that they can still spend time together until Emily comes back to New York. Aniston’s character responds to these words by erupting into applause; the enjoyable spontaneity of this is rendered via the swift, hard movement of her arms and hands, which, with her eyes fixed on Schwimmer’s Ross, seem to be acting almost independently of her.[1] This combines with Aniston’s use of her voice, who varies her pitch to bring it above and below her usual register (mirroring her body movement as she does so) to modulate her mocking, deliberately unconvincingly performed comment that this is the best news she has heard ‘since Le Poo died!’

Mocking

Already in the process of shifting towards anger, Aniston’s Rachel replies to Ross’ insistence that this development is painful for him too, by, as she herself announces, storming out of the apartment. During this movement, Ross’ interjection that it is her apartment she is leaving elicits her parting shot ‘Yeah, well, that’s how mad I am!’ She slurs the words ‘well, that’s’ a little, and this points to her character’s jaw being tightly clenched with anger, as well as the sense that her character is working out what words to say, less so to an actor running through a line that she has read, rehearsed and anticipated.

Storming out

As the above discussion bears out, this scene for Aniston is all about re-acting. Within roughly one minute of screen time, she deals with a very compressed unit that contains several gear changes, whereby she approaches each line of dialogue with a different verb (deflect, realise, mock, storm out) that she plays. Managing those gear changes both technically and emotionally is a difficult challenge; and Aniston flows through what are quick and potentially abrupt gear changes with a seamless through-line of actions. This is an example of a Stanislavskian principle highlighted by Sharon Marie Carnicke in relation to theatre as follows:

each actor searches for a uniting thread that links together all the characters’ actions to produce an overall sense of what the play conveys to the audience. Stanislavsky calls this unifying force through-action. (2010, 15; emphasis in original)

Crucially, Aniston manages this through-flow without making it look like she is (visibly) acting; her performance reads as her really hearing, taking in, responding to and working out what to do in relation to the news she receives. Aniston seems genuinely in the moment and rooted in her character throughout the scene. The moments when she is not speaking are not ‘dead time’ where she merely waits for her next line to speak (in our view, a sign of mediocre acting), but are actively used by her to experience the scene and construct her performance to facilitate these gear changes.[2]

Jennifer Aniston does not follow the sitcom style of acting that, as Brett Mills (2005) has discussed, displays its own artificiality and performativity. She stays within a realist/naturalist approach which, when done successfully, looks effortless and not ‘like acting’, but which, we argue, needs to be recognised and understood as highly skilled – indeed, as equally (albeit differently) skilled to excessive comic performance (see Naremore 1988 and Mills 2005). One aspect that underscores Aniston’s level of skill in Friends is that she locates herself here in a realist/naturalist approach within a particular genre and production context. As Mills has argued, the multi-camera shooting style with its wider framing and physical distance between camera and actor/character can be understood as ‘signal[ing] that it’s [comedy’s] not particularly interested in the psychology of its characters, or in them as realistic, believable, fully-formed human beings.’ (2005, 85) That Aniston directs her attention very much to her own character and to maintaining her own focus contributes to her successful portrayal of Rachel Green in Friends, a role for which she received an Emmy, Golden Globe and Screen Actors Guild Award.

Jennifer Aniston is, of course, not the only gifted actor in Friends; indeed, the sitcom’s remarkable success must be considered in relation to the strong performances of its main cast. What distinguishes Friends from many other specimens of the situation comedy genre is that it combines comic and dramatic performance modes. This point has already been made by Brett Mills, but we have a different understanding about the relationship between the two: Mills (2005) refers to a ‘flitting’ between these two modes, in which the comic mode involves the use of performance, defined via James Naremore’s work in relation to ‘forms of excessive display’ (Mills 2005, 69) and as distinct from acting, which is equated with a realist/naturalist approach. We would say that in Friends, the cast predominately ground their approach in realism/naturalism, in a way whereby even the more excessive and heightened comic moments are ultimately anchored and integrated into realism/naturalism.

This synthesis has contributed significantly to the success of Friends and Jennifer Aniston as Rachel Green, and is one of several reason why more detailed attention to her work is warranted. Drawing on Karen Lury’s work, Susan Berridge has previously proposed that:

it would be interesting to carry out more detailed audience research to explore further ‘how you feel, and why you feel, when you watch’ in relation to engagement with Aniston. (2014)

We would like to extend this suggestion and put forward that more attention to the details of Aniston’s acting would also usefully illuminate ‘how you feel, and why you feel, when you watch’ in relation to engagement to Aniston. Having taken further acting classes after attending a performing arts high school where she was called ‘a disgrace to the Russian theatre’, Jennifer Aniston has certainly been television’s (and cinema’s) gain.

Gary Cassidy is currently undertaking AHRC-funded doctoral research at the University of Reading. His thesis explores the rehearsal process of playwright Anthony Neilson, using filmed footage of rehearsals and interviews. He trained as an actor at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama and has thirteen years of acting experience – Equity name Cas Harkins – covering film, theatre, television and radio. Plans for future research focus on using his research methodology to explore the working processes of other contemporary theatre practitioners.

Simone Knox is Lecturer in Film and Television at the University of Reading. Her research interests include the transnationalisation of film and television (including audio-visual translation), aesthetics and medium specificity (including convergence culture), and representations of the body. She sits on the board of editors for Critical Studies in Television and her publications include essays in Film Criticism, Journal of Popular Film and Television and New Review of Film and Television Studies.

[1] This links to Robert Lindsay’s ‘demon hand’ in G.B.H. in some ways, in that both Aniston’s and Lindsay’s use of these body parts suggest that these (to different extents) take on a life and agency of their own. It is especially important to recognise Aniston’s use of her hands as skilled, given that this has received repeated, at times rather patronising attention.

[2] Aniston also takes this active approach to acting off the line during moments of audience laughter/applause.