I read with interest Christine Geraghty’s blog ‘Reappraising the Television Heroine’ from 6 September. Geraghty notes the prevalence in recent TV drama of the female detective, and she discusses various contemporary television series and their handling of female protagonists. The question she poses at the start of her blog is, what is it I’m looking for in a television heroine? This got me thinking, but not so much about female heroes. Why, I wondered, are some of my favourite female TV characters villains? And what am I looking for in a female villain?

The answer to the first question may be fairly obvious. In previous decades, powerful women were often villains because ‘real’ women or ‘good’ women didn’t have power. Of course, this means that female villains are often one-dimensional stereotypes: amoral, usually overtly sexualised, generally flashing lots of evil cleavage. Even these limitations can produce memorable characters. I’m sure I’m not the only one who enjoyed the risible Helen Cutter in Primeval for her laughably predictable lines and selection of low-cut tops. Even Helen’s action figure was defined by its evil cleavage.

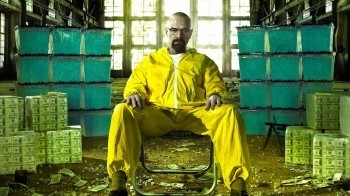

The increase in complex characterisation in all kinds of television drama, and the equally discernable vogue for moral ambivalence has given us a slew of dark heroes and dubious protagonists, from Batman to Dexter Morgan. Characters who might earlier have been simply villains have taken centre stage in their own television shows: Vic Mackey dominated The Shield, and Walter White’s moral decline has made Breaking Bad one of the most talked about TV shows as it winds up its final season. Some of the female protagonists we’ve seen in detective drama are almost the equivalent of damaged, dark or deficient male heroes: Sarah Lund (Forbrydelsen) is a typically driven police officer who neglects her personal life and relationships to the point of isolation. Well before this current rash of female crime solvers, Xena sought redemption from a dark past by using her martial skills to help people (Xena: Warrior Princess). But what about villains?

There are also some memorable TV bitches, especially in soap opera, where the domestic arena allows female characters to shine. One of the reasons I love female villains so much is the superb Alexis Carrington Colby from Dynasty, watched during my formative years. The bitch characters of TV have also evolved, now often forming part of the team or at least a key part of an ensemble cast. Lilah Morgan in Angel was never just a villain and developed many layers of complexity in the show’s five-year run, for example.

But my favourite female villains aren’t just bitches. They’re über-bitches and supervillains—they’re Evil Queens. And I know exactly who’s responsible for this: Servalan, Supreme Commander of the Terran Federation’s military forces, and then President of the Federation, in Blake’s 7 (1978-1981). Servalan was astonishing.

She is a military commander but she wore the most extravagant, impractical outfits (there are whole webpages dedicated to them). She has one of the shortest haircuts ever seen on a female TV character, long before Ripley appeared in Alien3 with a shaved head. In true evil queen and TV bitch style, she gets all the best lines and, often, the last word. She isn’t infallible and sometimes does get into trouble—but soon regains control of the situation. She’s a true power-grabbing, back-stabbing, I-want-to-rule-the-world villain. And, to me, one of the best things about her is that Blake’s 7 never offered an explanation for a woman acting like this. Yvonne Tasker, in her study of action cinema, points out that in order to present a strong, active female hero, most stories of the 1970s had to provide an ‘excuse’ or a justification for their protagonists behaving in this way. Female villains like Queen Yllana in the admittedly tongue-in-cheek B movie Queen of Outer Space (1958) are given similar motivations to explain their ‘unfeminine’ actions. Servalan never had or gave an excuse. Like any male evil megalomaniac, she just wanted power and she took it.

Actor Jacqueline Pearce recounts how Terry Nation wrote Servalan as a man, and only changed the sex of the character halfway through the first script, explaining, ‘I think this is why Servalan is probably so interesting.’ Servalan wasn’t in every episode of Blake’s 7, but she had a massive impact. The many fan montage videos posted on YouTube highlight her appeal as the epitome of the Evil Queen. One, titled ‘Supreme Queen’, accompanies its set of clips with Queen’s track ‘Killer Queen’, another posts the ‘tribute to Servalan’ with the added note, ‘Music is “I’m a Bitch” by Meredith Brooks’.

In between Servalan and today there have been other Evil Queens on television, including the Borg Queen (Voyager), Callisto (Xena: Warrior Princess), Glory (Buffy the Vampire Slayer) and Morgana (Merlin). But my current top Evil Queen on TV is exactly that, the Evil Queen from Once Upon a Time (2011-), aka Regina Mills.

Regina is the kind of complex, multilayered villain we’ve seen previously mostly played as male. I find Once Upon a Time so fascinating because it does a kind of role reversal with gender. Many of its characters are boring, one-dimensional, passive, needy and only there as eye candy. They’re mostly men. The one male character who’s given depth and interest is the villain. The majority of female characters, on the other hand, are active, interesting, complex and engaging. And this includes villains as well as heroes.

Taking fairy tale characters as the main cast for a TV drama and relocating them in a stereotypical small American town (Storybrooke) as ‘regular’ people might seem a dubious premise, despite the recent trend for fairy tale films. When I started watching Once Upon a Time, I was convinced it was going to be too saccharine, overwhelmed by happy endings and all-American ideologies. It continues to surprise me with what it brings to its characters. The main protagonist, Emma Swan, has a very shady past and gave her son up for adoption years ago. Another key female hero, Snow White aka Mary Margaret Blanchard, is shunned by the townspeople in the first season for conducting an illicit affair with a married man, and narrowly avoids becoming a murderer in the second. And the town mayor is none other than Regina Mills, the Evil Queen from the Snow White story, who married a widower, hunted down her husband’s daughter when she turned rebel, and steals her enemies’ hearts from their chests—literally.

Regina consistently has the best lines, the best scenes and the best outfits. As the mayor, she wears power suits; as the Evil Queen her riding outfits include top hats and leather trousers worn beneath a floor-length split skirt.

Like Servalan she can rule, fight, and win in memorable, begging-to-be-cosplayed attire. Like Servalan her outfits might be sexy and her character seductive, but she is not reduced to an over-sexed female villain. As both the mayor of Storybrooke and Queen of the Enchanted Forest, Regina’s power is worldly, political power. Coupled with magic and a strong drive, this makes her a force to be reckoned with.

We are given reasons for Regina’s action and character, but these are not excuses to explain away a female villain. They are backstory, in a show that gives each and every character backstory. And Regina’s backstory is closely paralleled with that of the show’s main male villain, Rumplestiltskin aka Mr Gold. Both have family tragedy in their past. Both are motivated to maintain a strong relationship with their child, Rumplestiltskin with his lost son Baelfire, and Regina with her adopted son, Henry (Emma’s biological son). Both seek revenge against those they think have wronged them deeply, and see the world as something to be manipulated to their own advantage. Notably, though, it is Rumplestiltskin who is most consistently defined by heterosexual romance. His desire for vengeance and his transformation into the Dark One is fuelled by the loss if his wife. His persisting remnants of humanity are associated with Belle and his ongoing need to rekindle that relationship. Regina’s backstory includes a love affair with a stablehand in one world, and a fling with the town sheriff in the other, but these romances are not used to define her.

Regina’s history acquires further depth as we discover more about her mother, Cora. We find out (in ‘The Miller’s Daughter’ 2.16) that before becoming an evil enchantress, Cora was a miller’s daughter, as in the Rumplestiltskin story, and her will to power is contextualised within a system of unequal class and gender dynamics. Cora is an über-bitch and master-manipulator, not least of her own daughter, but we can understand why a disenfranchised member of the working class might want real world power to escape oppression. This episode was followed later in the second season by another simply called ‘The Evil Queen’ (2.20), which clearly articulated something hinted at in Regina’s character all along. She should be, and believes she is, just the Queen, a woman trying to the right thing; it is others who have labelled her the Evil Queen.

As self-deluding as Vic Mackey, and as engaging, Regina is capable of eliciting our understanding and often our sympathy, as well as our horror. Her story and its layers deal with specifically female experience: her difficult relationship with her mother, an equally difficult relationship with her step-daughter, and with her adopted son (who soon knows, and seems often to prefer, his biological mother), form the basis of many of her plot lines. Moreover, we are convinced that she does love Henry, even as we see her prepare to sacrifice the whole town so she can be reunited with him. She is a truly complex villain. Her actions are frequently unforgivable and appalling, yet she sometimes seems to teeter on the verge of redemption.

That would be a disappointment, frankly. I’m not holding out for a hero. I’m not rooting for Emma and Snow and Charming. I’m watching Once Upon a Time for her. Long live the Evil Queen.

Lorna Jowett is a Reader in Television Studies at the University of Northampton. She is the co-author with Stacey Abbott of TV Horror: Investigating The Dark Side of the Small Screen (2013) and author of Sex and the Slayer: A Gender Studies Primer for the Buffy Fan (2005). She has published many articles on television, film and popular culture, and is particularly interested in genre, gender and television drama.