Although Netflix’s approach to genre is different to those predominant in screen studies, the streaming site provides useful contextual materials for teaching on the subject. At several points last semester Netflix proved relevant to discussions of genre as part of an introductory Film Studies module, as well as an Honours ‘Film Genres’ module. Because, leaving the complex theoretical debates about genre to one side, the streaming platform indicates much about how genre works today from the perspectives of industry and audiences—and so it can help to address the question of what purposes does genre serve, and for whom?

When considering the relationship between genre and marketing, a click on a given Netflix ‘genre’ or ‘subgenre’ quickly generates a bank of promotional imagery— materials that can make common marketing conventions immediately apparent: such as pink and red colour schemes for romantic comedies, or orange and black for action films. Also, since we can choose to order a given Netflix genre category by year, it’s possible to trace aspects of a genre’s evolution over time. While this would mean drawing from the site’s limited and ever-changing catalogue of content, it nonetheless allows students a user-friendly way to engage with examples from various periods (assuming they have access to an account).

Even when Netflix departs strongly from critical approaches, such as by listing documentary as a genre (at odds with our conception of it as a mode of filmmaking), this can be a useful way to discuss genre as malleable concept, meaning different things to different groups. In fact, given that Netflix also lists ‘mockumentaries’, separately, as a subgenre of ‘comedy’, it raises an interesting question to pose to students: why might screen studies scholars agree that the mockumentary is a subgenre of comedy, even if they don’t consider documentary itself to be a genre?

More generally, the platform’s complex approach to categorisation is valuable in that it offers rich examples of subgenres and genre hybridity. For instance, if deconstructing horror film conventions is the aim, then Netflix helpfully distinguishes a subgenre of ‘Serial and Slasher Films’ from those of ‘Zombie Horror Films’, ‘Vampire Horror Films’, ‘B-Horror Films’ and ‘Horror Comedies’, among others.

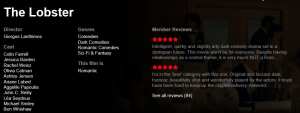

Pointing to the distinction Richard Maltby makes between Hollywood as ‘a generic cinema’ rather than ‘a cinema of genres’ (1995: 107), clicking on an individual film provides a list of genres to which it can be said to belong; based on specific generic components. The value of this system becomes clear in relation to a feature like The Lobster (Lanthimos, 2015), a notably self-aware film which Netflix classifies as ‘sci-fi and fantasy’ as well as ‘comedy’, ‘dark comedy’ and ‘romantic comedy’. In keeping with the film’s playful approach to genre norms—which includes the use of absurdist humour and an ahistorical dystopia to question the norms of heteronormative coupling—the mix of categories encapsulates the film’s generic positioning better than any single genre label could.

In its quest to attract and retain customers, Netflix has invested heavily in identifying and utilising generic components. As Alexis Madrigal explores in ‘How Netflix Reverse Engineered Hollywood’ (2014), the company has created close to 77,000 micro-genres by combining human analysis with algorithms:

Using large teams of people specially trained to watch movies, Netflix deconstructed Hollywood. They paid people to watch films and tag them with all kinds of metadata. This process is so sophisticated and precise that taggers receive a 36-page training document that teaches them how to rate movies on their sexually suggestive content, goriness, romance levels, and even narrative elements like plot conclusiveness. They capture dozens of different movie attributes. They even rate the moral status of characters. When these tags are combined with millions of users viewing habits, they become Netflix’s competitive advantage.

Most of these micro-genres do not appear on the site, but some of them can now be accessed using codes listed elsewhere, as well as through a Twitter account that derives content from an automated generator (one created by Madrigal and Ian Bogost, a Professor of Interactive Computing at Georgia Tech).

From the perspective of teaching, these highly specific micro-genres—such as ‘Post-Apocalyptic Workplace Westerns’ or ‘Imaginative Vampire Action Movies Set in Prehistoric Times From the 1970s’—provide a humorous endpoint from which to think about the value/futility of genre classifications, and the degree to which genres rely on small variations from a tried and tested formula. While the micro-genres generated by the bot are defined from Netflix’s data, the labels can include a longer list of descriptors than the site generally makes visible. The wonderfully evocative ‘Deep Sea Horror’ is an accessible option. But, given that four of the seven current listings are dedicated to the Sharknado franchise, does it really warrant its own category? Let the students decide…

Jennifer O’Meara is a Teaching Fellow in Film Studies at the University of St Andrews.

Works cited:

Richard Maltby, Hollywood Cinema: an introduction, Oxford; Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1995.