The perfect set for every home

I love going to archives. From my first visits, I knew that this was going to be the most exciting part of my research. As a researcher of television history, I initially expected to spend my time just at the BFI and the BBC Written Archive, but as my research veered towards the material history of the television set I had to be a little more creative. Finding the traces of television’s material history is a challenge and large amounts of it are sprinkled across different archives, or simply lost. I’ve been to archives of art, design, social history, broadcasting, domesticity, magazines, science, and technology, all of which contained material relating to how the television set became an integral part of our lives in the postwar period.

Archives are peculiar places; each one is unique, with its own slightly different sets of rules and codes. Some are in basements, others in purpose-built buildings and you never know quite what to expect. Archives are really quiet, often stuck back in time, with only pencils and whispers allowed. That musty smell is amazing. When you’re given your box or file there’s a sense of excitement about what you will find. There’s something a little mystical about it too; these boxes are like little missives sent up from the past, waiting to reveal hidden secrets to you. I was always jealous of the staff at archives; after you give them your request they disappear into the unknown innards of the archive to retrieve the files. They impart to you pieces of your research in bite-sized packages. I wish, I’d think to myself, that I could go with them into the bowels of the archive: what treasures must be there!

It was with great enthusiasm, therefore, that I accepted a placement with the National Media Museum to help them catalogue their Pye/C.O. Stanley archive. I was given 45 boxes of material, a key to the archive storage (which happened to be an air hanger in an ex-RAF airfield in Wiltshire), and three months to find out what was inside. Walking past a disused tornado fighter jet with my own trolley each day to fetch a new box gave me unprecedented levels of both excitement and mysticism.

The archive relates to the life and work of C.O. Stanley, who was the head of Pye Ltd from 1928 until 1966. Pye Ltd, in its heyday, was a conglomerate of companies, specialising in a wide array of electronic instruments and was a benchmark of British electronics manufacturing in the mid-twentieth century. Much of this success was down to C.O. Stanley, who bought the company in 1928. It was Stanley’s pioneering vision, which steered the company in the direction of radio and television, and it became a leading manufacturer of radio and television sets. By the 1960s, however, this vision had failed, and the company was in dire straits before being sold to Philips in 1966.

Inside the archive I discovered how the archive itself came into existence and how it was nearly consigned to the skip of history; it was only because of the efforts of C.O. Stanley’s grandson, Nicholas Stanley, that it now sits in one of Britain’s national collections. Nicholas Stanley, in his efforts to trace the history of his grandfather, managed to pull together the files of a one-time giant of the television and radio industry, providing researchers like me with unique insight into television’s manufacturing history.

The archive itself is a sprawling collection held in 45 boxes, consisting of huge amounts of correspondence, minutes, accounts, employee files, photographs, trade literature and the personal papers of the Stanley family. In it, I did indeed find a treasure trove of material relating to British television history (alongside children’s letters asking for more sweets at boarding school, marriage and divorce certificates, 1970s family photos from Greece and a few mouldy ledgers). I was struck most by what the archive revealed about the place of television manufacturers in television’s development, both as a technology and a medium. I had not expected that Pye and its commander in chief C.O. Stanley had played such a large role in advancing British television.

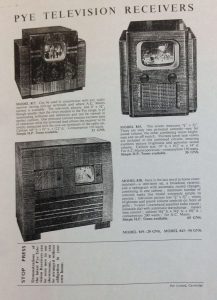

Pye television receivers pre-war

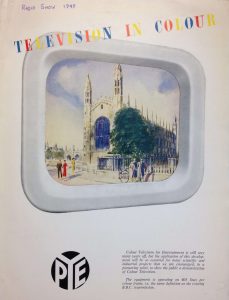

While sifting through these boxes, it became clear that C.O. Stanley had seen the potential of television early on and had driven Pye, as he had done with radio in the 1920s, to nurture this new technology. Pye was quick to respond to the developments in television broadcasting and marketed a 9-inch receiver to coincide with the launch of the BBC television service in 1936 and, by the Second World War, had a wide range of receivers on sale. The leaflet above shows the range of Pye receivers on sale before the war.[1]All images are copyright C.O. Stanley archive/National Media Museum Pye were a frontrunner in developing television sets, both before and after the war; as early as 1949, Pye was demonstrating colour television at the annual trade fair Radiolympia, which the advert pictured shows. Pye pioneered designs for valves, cathode ray tubes and picture control. Beyond just making television sets, Pye developed studio equipment including cameras and outside broadcast vehicles. A sub-division of Pye, Pye TVT, was created to focus on this aspect of television, and Pye studio cameras were used by the BBC and eventually ITV. The National Media Museum holds a whole other archive just related to the Pye TVT division.

Television in colour

The archive was full of promotional material for the range of products that Pye offered, something which I have struggled to find in other archives. It reveals the various ways that Pye communicated its television sets to the public: conferences, exhibitions, leaflets, demonstrations, adverts and in shops. These kinds of manufacturing ephemera tell us how television was conceptualised in this period and how this conceptualisation was communicated to potential consumers.

Woman in Pye sales shop

The archive is also interesting for what it tells us about television’s history as a technology. While I was not able to decipher much from the service notes and patents in the archive, I did find that there was an array of material relating to how television was manufactured and by whom. I was intrigued by photographs of the workers making television sets in the Pye factories. I had not realised how many women were employed in radio and television factories from the 1930s onwards. I was particularly struck by a photograph of a woman, beautifully dressed, riveting a chassis (pictured below). I realised I had not considered how television sets were made, or who made them, despite how much time I had spent thinking about how they were advertised, sold and displayed. Alongside these, there were employee files, employee handbooks, photos from staff sports days, all of which offer us a glimpse into what working life was like for those men and women who were building the radios and television that were appearing in homes across Britain.

Woman riveting chassis in factory

Beyond just manufacturing, Pye played a role in the development of British broadcasting, as C.O. Stanley was a leading advocate of commercial television in Britain. Stanley was a respected voice in the industry, who gave various speeches about television and its future, such as one entitled ‘Television: Today and Tomorrow’ given to the Royal Institute of Radio Engineers in 1949. Having transcripts from these speeches means we have access to how television was spoken about in its early days and how its future was imagined at a time when it remained uncertain.

Stanley believed that the only way to sell more sets and to develop the medium further was to introduce competition into broadcasting. Without it, he believed, the service would never attract enough viewers, nor would the expense of a set seem justifiable. This viewpoint is supported by the Mass Observation survey from 1949 about television, when multiple respondents write that, until the television service improved, they would not consider buying a set. Letters in the archive show Stanley’s passionate belief in independent television and the benefits it would bring. They show that Stanley was sensitive to the prevailing distaste in this period for anything commercial, hence why the term ‘independent’ television was preferable to ‘commercial’ television.

Sunday Times newspaper, 1961

Alongside Norman Collins, former BBC director of television, and Robert Renwick, a peer and industrialist, Stanley played a key role in lobbying the government for commercial television. This union between men from broadcasting and industrial backgrounds shows how television was, at this stage, still developing as a technology and a medium, and that both these aspects were equally important to its development. As we know, their lobbying was a success and in 1955 independent television was launched. This development in how broadcasting was operated, the archive shows, was in part down to the ambition of individuals and their desire for financial gain. The archive holds a copy of The Sunday Times special on ITV from 1961 in which Stanley, Collins and Renwick are all pictured, indicating that they are the ‘men and the money’ behind ITV.

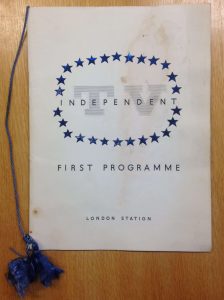

ITV opening night programme

Another gem from the archive is a programme for the opening night of ITV, adorned with shiny blue stars with a tasselled string in its spine, the programme is a physical emblem of the beginning of a new television era. I recently attended a lecture by Jamie Medhurst on the early days of the BBC television service, in which he showed a picture of the BBC’s programme for the opening of the television service in 1936. The BBC programme, in contrast, consisted of a piece of card with black typeface. No shine or sparkle in sight.

It is interesting to speculate how television would have developed in this country were it not for commercial television and its attendant interests. What I find striking about C.O. Stanley’s intervention into broadcasting is that it highlights that, despite the intentions of public service broadcasting, television was always, in part, a commercial venture: the set itself needed to be manufactured, sold and advertised. C.O. Stanley understood this connection only too well, knowing that the profits and success of Pye rested on the development of a successful television service. On this score, the archive is particularly revealing.

Spending time with this archive was a rare opportunity; I am only one of a handful of researchers who have seen it. I hope that my work listing its content has brought it one step closer to being more accessible to other researchers. Getting unrestricted access to a whole collection has helped me understand the messy way in which archives are delivered and the task that archivists undertake to make it accessible. I also see now that the portions of it that are handed out to us in the reading room of the archive are only partial. We step into an archive with an idea in our head about what we are looking for, which shapes the material given to us. Through this work, my understanding of television’s development from the 1930s has been broadened. I see now that its technological, manufacturing, consumer and broadcasting histories are all heavily interwoven; a relationship that surely deserves more detailed dissection.

Emily Rees is a postgraduate researcher in the department of Culture, Film and Media at the University of Nottingham and is funded by the Midlands3Cities doctoral training partnership. Her thesis focuses on the domestication of television in Britain 1946-1976, exploring the ways in which a “television lifestyle” emerged during this time.

References

| ↑1 | All images are copyright C.O. Stanley archive/National Media Museum |

|---|

What a terrific article! How wonderful to be reminded of other people with a passion for delving into the archives in this manner and discovering all the wonderful things about television’s past. And so evocatively written!

Just the tonic I needed when my enthusiasm for some of this stuff was starting to flag! Many, many thanks!

All the best

Andrew